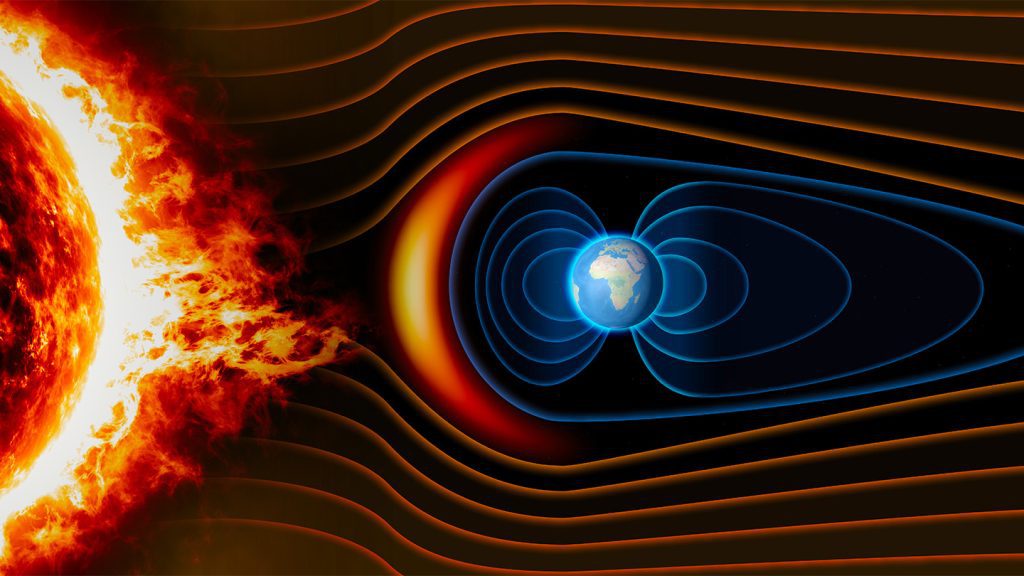

Earth's magnetic field shields life from harmful cosmic radiation. But at some point between 590 million and 565 million years ago, it appears that the protective layer was much thinner — with significant impacts on the development of life on Earth with widespread consequences for the evolution of life on Earth, researchers say.

A less strong magnetic field could explain the higher levels of oxygen found in the Earth's atmosphere and oceans at that time — and the resulting increase in large marine animals, according to the team's report in the May 2 Communications Earth & Environment.

Earth's magnetic field is created by churning molten iron in the planet's core. At a strength of only 0.00005 tesla, it's about one ten-thousandth the strength of the field in a magnetic resonance imaging machine. This might not seem like much, but it's strong enough for several animals to sense and use for navigation (SN: 3/29/24).

The strength of Earth's magnetic field varies, usually over periods of thousands to millions of years. For example, rocks dating back 565 million years in Canada contain magnetic minerals indicating that Earth's magnetic field was only one-tenth as strong as it is today (SN: 1/28/19). Our planet's field occasionally weakens during events called magnetic field reversals, but it's unlikely that these rocks are showing those relatively short-term events, says John Tarduno, a geophysicist at the University of Rochester in New York who was part of the team studying the Canadian rocks (SN: 2/18/21).

Now, the same team has studied rocks from Brazil dating back to about 590 million years ago. Earth's magnetic field was even weaker at that time, the researchers discovered — just one-thirtieth of the modern-day strength. That's the lowest magnetic field strength ever recorded for our planet, Tarduno says. "The field nearly completely disappeared."

If Earth's magnetic field remained low during the roughly 25-million-year period between those samples — and less precise data from other teams indicate that it did — it's a remarkable coincidence, Tarduno notes. Earth's magnetic field was significantly weaker right around the time of the Ediacaran Period, when oxygen levels increased in both the atmosphere and oceans; rock records indicate higher-than-normal oxygen levels around that time. This is also a time when large animals began to flourish in the world's oceans.

Tarduno and his colleagues suggest in their new paper that there may be a connection. A weaker magnetic field would have meant less protection from energetic cosmic particles. "Our shield was down," Tarduno says. These particles would have broken apart water molecules in the early Earth's atmosphere. Hydrogen, being extremely light, would have easily escaped into space, while oxygen would have remained. Over time, this disparity would have led to a more oxygen-rich atmosphere and oxygen-filled oceans, the researchers propose.

According to Tarduno and his team, the bigger animals that appeared in the Ediacaran Period, as seen in the fossil record, would have required more oxygen. Tarduno explains that larger animals need more oxygen than smaller ones. This increase in oxygen would have made it possible for larger life forms to thrive.

Joe Meert, a geoscientist at the University of Florida, who was not involved in the research, acknowledges that there are significant conceptual advancements in this study, but considers the measurements to be reliable. He finds studies like this one helpful in introducing groundbreaking concepts. Meert appreciates papers that thoroughly present ideas and information.