On June 4, 2021, amidst blooming saguaros and prickly pear cacti, a wildfire erupted in the Sonoran Desert in central Arizona. Its early flames fed on nonnative grasses dried out by a prolonged, severe drought, and the fire was additionally fueled by the weather. A nearby weather station registered a temperature of 36° Celsius (97° Fahrenheit). And it was so dry that the blades of firefighters’ bulldozers — used to clear brush — ignited small flames as the heavy vehicles dragged on rocks.

Ecologist Mary Lata of the U.S. Forest Service initially heard about the fire over the radio while doing fieldwork off to the north, in the Tonto National Forest. “I recall hearing them talking,” she says, “and gradually realizing they weren’t going to catch this one.”

By June 7, winds had blown the wildfire east-northeast into the Pinal Mountains, in the Tonto’s southern reaches. The flames quickly moved up, surpassing rock cliffs — defying the expectations of experienced firefighters, Lata says — and sweeping through vast, unbroken stretches of chaparral. When the fire reached the highest elevations, crowned by pine forests, it engulfed those too.

The Telegraph Fire, as it’s now known, became so intense that it started to create its own wind, its rising heat producing a convective force that pulled in air from the sides, Lata says. “Of all the fires I’ve worked on, Telegraph was the nastiest.”

On the fifth day, the fire approached the city of Globe. By then, it had already consumed an area larger than Globe five times over. The blaze would be remembered as one of the biggest fires in Arizona history, engulfing some 700 square kilometers of land — equivalent to about half the area of Phoenix. But the fire would not engulf Globe.

Instead, on a ridge just outside the city, the Telegraph Fire encountered a barrier, the remnants of a previous blaze.

Four years earlier, lightning had ignited the Pinal Fire in this area, albeit under milder conditions. Recognizing the need to clear out vegetation that might fuel future blazes, fire crews allowed the fire to consume litter, seedlings and other brush near the ground. Crews even set fires themselves, expanding the fire’s breadth.

Reaching the remains of the Pinal Fire, the Telegraph Fire “shifted from a fast-spreading canopy fire, where it was killing about 60 to 70 percent of the trees it encountered, to a slow-moving ground fire, where it was killing about 1 percent of the trees encountered,” says Kit O’Connor, an ecologist at the Forest Service in Missoula, Mont. Eventually, the fire stopped about a kilometer away from a neighborhood in Globe’s outskirts.

If it weren't for the Pinal Fire, the Telegraph Fire would have burned into town, Lata says. “There’s nothing we could have done to stop it.”

The choice to allow the Pinal Fire to continue burning was influenced by a new plan for managing wildfires, called potential operational delineations (PODs). These divisions divide the land into zones where fires can be feasibly controlled. The boundaries are established before the fire season begins using a combination of artificial intelligence and local knowledge. A POD network can help land managers identify opportunities to control wildfires that start under manageable conditions. The goal is that if subsequent fires occur under extreme conditions, there will be less vegetation available to fuel their intensity.

O’Connor, who has been involved in creating PODs in the Western region, explains that if a fire is moving quickly toward homes and there is no cleared area or fuel-free zone surrounding the homes, they are likely to be destroyed.

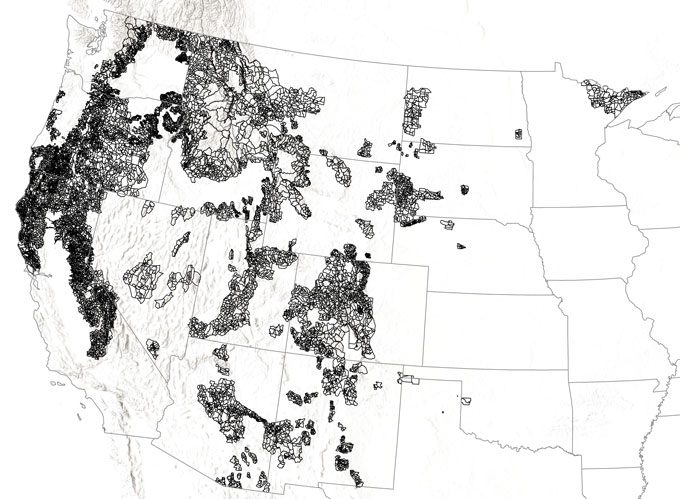

Today, POD networks cover the Western region, including California, Washington, and extending as far east as Minnesota. This includes approximately 70 national forests, state, and private lands.

However, these wildfire strategies face challenges as they expand. Keeping them updated to reflect landscape changes is a crucial but difficult task. It is also unclear whether they will protect the interests of the Indigenous people who have managed the land for centuries.

However, there is a significant need for a new approach.

Climate change and years of ineffective fire management have continuously fueled wildfires in the Western region. fires in the West (SN: 6/17/22). The average area burned by western fires each year has more than doubled compared to four decades ago. During the record-breaking 2020 wildfire season in the region, fires burned an area larger than the state of Maryland. These fires now destroy more than double the number of homes and buildings compared to the beginning of the century—from 2010 to 2020, fires destroyed more than three structures for every 10 square kilometers burned. Scientists predict that more land and homes will burn in the future. Working with manageable wildfires, or those that occur in favorable locations under good weather conditions, to clear dense vegetation could help reduce the risk posed by larger fires to homes and people across the Western region. O’Connor expresses that while fire cannot be eliminated, there is potential for significant benefits in finding opportunities to utilize it. Collaborating to change

On December 4 of last year, there was no visible smoke in the sky above Monterey, Calif. The most critical months of the state’s fire season—July to November—had passed. Nonetheless, as seasons come and go, so do the fires. Therefore, on this day in Monterey, a gathering of firefighters, conservationists, and researchers had assembled in anticipation of the fires that were yet to come.

Christopher Dunn explained to the group, “We are caught between two paradigms.” Displayed behind him were two images: a painting from 1905 depicting a member of the Blackfeet Tribe setting fire to the grass with a flaming torch, and a staged photo from 1955 showing a fire brigade of jeeps and a helicopter heading toward a smoking fire in the distance. Dunn, a forestry researcher at Oregon State University, stated that both approaches are necessary.

In 1910, only five years after the Forest Service was established, a major fire called the Big Blowup occurred. It involved around 1,700 wildfires in Montana, Idaho, and Washington, burning over 12,000 square kilometers in just a few days. As a result, Congress passed the Weeks Act in 1911, which effectively banned the traditional use of fire by Indigenous people. They had used fire for a variety of purposes, from corralling bison to clearing areas for crops.

corralling bison

to clearing brushy areas for crops. Then in 1935, the Forest Service implemented the “10 a.m. policy,” requiring that every reported fire be put out by the 10th hour of the next day. Fast-forward to today, and approximately 98 percent of U.S. wildfires are extinguished before they reach 1.2 square kilometers. Stopping most wildfires has allowed dense, continuous layers of vegetation to grow. Under extreme conditions, these fuel loads can feed large blazes like the Telegraph Fire. On the other hand, a landscape with frequent fires tends to have a mix of areas that burned at different times in the past, with vegetation at various stages of regrowth. These diverse fire landscapes, with their rich mix of habitat types, can enhance an area’s biodiversity, according to scientists. Additionally, recently burned areas have reduced fuel stocks, which can inhibit the spread of wildfires even in extreme conditions, like the Pinal Fire scar did.

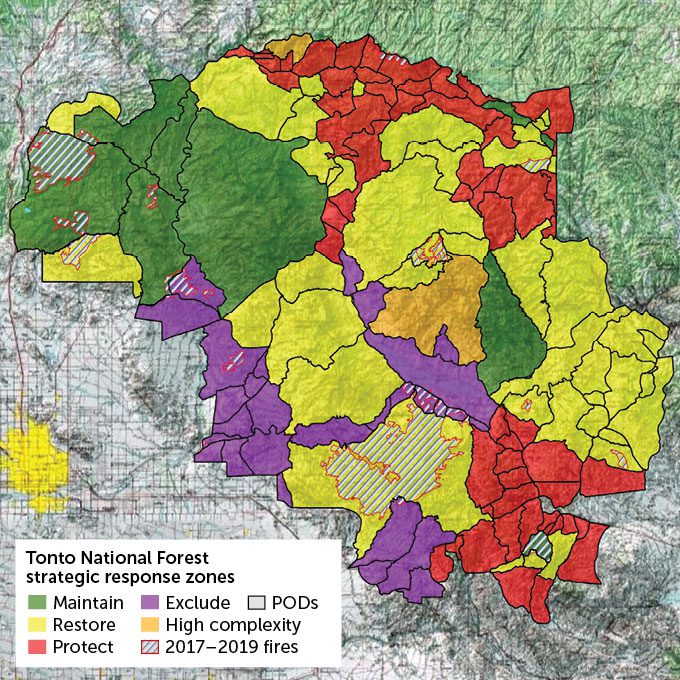

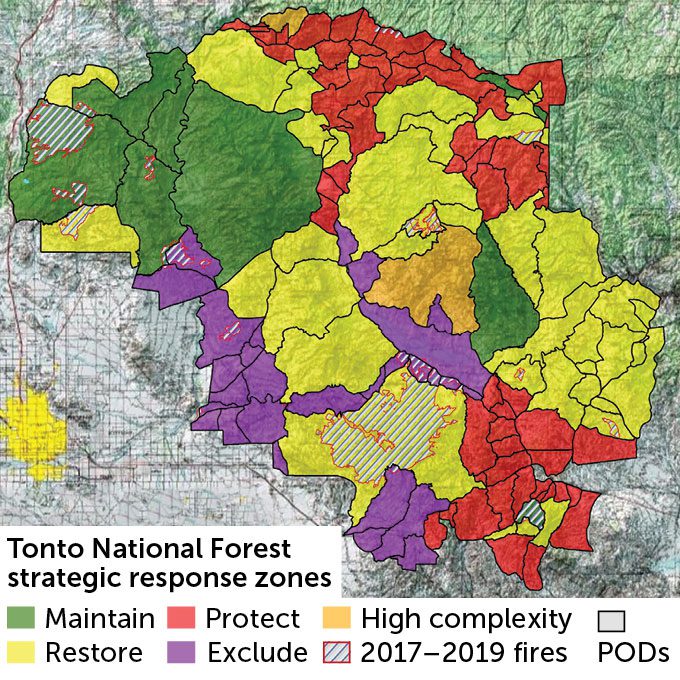

“We want more fire,” Dunn said. He spoke to a group focused on creating PODs for lands in and near California’s Los Padres National Forest, situated along the state’s mountainous Central Coast between Monterey and Ventura. The Tonto National Forest in Arizona is divided into PODs, which are zones where wildfires can be contained. Color-coding is used to plan responses: In green “maintain” zones, fires may be beneficial. In red “protect” zones, fires pose a high risk to people and should be put out. In purple “exclude” zones, fires should be extinguished to protect the Sonoran Desert ecosystem. In yellow “restore” zones, fires may be safe under certain conditions. If managed properly, “high complexity” orange zones could become restore zones. First outlined in a 2016 paper produced by the Forest Service in California’s Sierra Nevada,

PODs are, at their simplest, polygons drawn on a map

POD network

. Their boundaries usually follow features from which fire can be safely and effectively contained, such as ridges, roads, or rivers. These boundaries can also guide where prescribed burning, selective logging, or other actions could be taken to reduce vegetation and minimize fire risk.

POD networks resemble geometric cobwebs, often created during the fire off-season in workshops attended by land managers, tribal members, fire crews, researchers, and other local stakeholders. The workshops allow the proactive sharing of knowledge that might otherwise remain isolated, according to O’Connor. “It really helps to involve all the different players in the long-term management of a piece of ground.” For the second part of the workshop, Dunn and his colleagues laid out large topographic maps on tables in two rooms, displaying various sections of Los Padres National Forest and nearby lands.Some of the maps were filled in where wildfires had burned recently or where actions to reduce flammable vegetation had taken place. Other maps were colored by a machine learning program that uses data on topography, fuel characteristics, road networks, and historical fires to predict and map the most effective locations for stopping a blaze.

This model for a potential control line

isn't as familiar with the land as local land managers, but it can assist them in reaching an agreement, according to O’Connor.

There were also maps colored by another algorithm, called the suppression difficulty index model . It indicates “how difficult it would be to move people and equipment to any part of the landscape,” O’Connor explains. In other words, where it’s most challenging to fight a fire from.

Dunn asked workshop participants to draw PODs on these maps, using the shaded and colored areas as guides for marking boundary lines. With markers in hand, attendees began drawing dark lines on the maps, sometimes following features highlighted by the models, other times diverging. Conversations filled the air. “The only way to keep going this way is a really gnarly ridge.”“We used this section on the Dolan Fire. It was good.”

“That road doesn’t go all the way through anymore.”

In some national forests, PODs are combined with another tool, the Quantitative Wildfire Risk Assessment, or QWRA. These assessments outline where a fire may be most damaging, considering the locations of homes, endangered species habitats, timber resources, and other assets.

When combined with QWRAs, basic POD networks transform into colorful mosaics, mainly in the colors of a stoplight. When PODs are shaded green, they indicate areas that could benefit ecologically from fire and where a fire is unlikely to damage resources. Here, allowing wildfires to burn may be appropriate. On the other hand, a red POD contains many resources at risk of being lost in a fire. Any emerging fires should probably be stopped. Some PODs fall into a yellow category: The POD could benefit from fire, but only under the right conditions.

With these ratings available, land managers can plan how best to handle fire. The 2017 Pinal Fire was in a yellow POD, which firefighters allowed to burn.

“It does.”

After the Monterey workshop, the hand-drawn lines were converted into digital format and made publicly accessible for viewing on the Risk Management Assistance Dashboard, an online platform developed by the Forest Service in 2020 where users can follow up with comments and suggest alterations.

PODs can also be updated in follow-up workshops in subsequent years. But gathering people year after year is easier said than done. “For [PODs] to be useful, they have to be updated,” says forest and wildlife researcher Michelle Greiner of Colorado State University in Fort Collins. The landscape changes over time. But keeping PODs up-to-date, or even in the awareness of land managers and fire crews, “takes a lot of time and a lot of capacity,” she says, “and I think it kind of remains to be seen if that’s something that’s going to be sustained.”

The Forest Service has hired regional analysts to keep POD networks updated and relevant, according to O’Connor. He wants to expand on what’s already been done and ensure the tools aren’t forgotten.

POD networks cover around 70 national forests, state and private lands in the United States. Some new ones, like the Los Padres National Forest, are not included.

U.S. Forest Service

Cultural conflicts

These burning practices, along with natural fires, have maintained forest stability in the western Klamath Mountains for a thousand years, as shown in a 2022 study.

In fact, Karuk and Yurok burning practices, along with natural fire activity, maintained the stability of a forest in the western Klamath Mountains.

The Forest Service district ranger and a member of the Hoopa Tribe, Nolan Colegrove, stated that the landscape in the Klamath Mountains has been drastically changed by suppressive fire policies over the last century. For over a millennium, Indigenous people's setting of frequent, low-intensity fires yielded many ecological benefits, such as promoting elk habitat and restoring nutrients to soils, according to a 2022 study.The landscape in the Klamath Mountains, where Colegrove works, has been drastically changed by suppressive fire policies over the last century. The North Coast Resource Partnership, or NCRP, has led the development of a unique POD network in the Klamath Mountains. the North Coast Resource Partnership

, or NCRP, an organization helmed by elected officials from the region’s tribes and counties, led the development of a one-of-a-kind POD network in the Klamath Mountains.

Representatives from local tribes, county governments, the Forest Service, industrial timber, municipal fire departments, homeowners associations, and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection were invited to NCRP’s POD workshops. Bringing everyone together provided insights into past failed efforts to reduce wildfire risk. The POD approach has led to disputes as the data in PODs is publicly available, while much of the ecological and cultural knowledge possessed by tribes may be too sensitive for public disclosure. Indigenous people may help delineate POD boundaries on their historic lands in POD workshops while withholding sensitive tribal resource information, which could later lead to destructive outcomes when fire crews treat those areas unexpectedly.Vikki Preston, who is part of the Karuk Tribe and works with cultural resources, says that many important tribal areas are located on high ground where fire lines and other firefighting measures are often made. When non-tribal fire crews come in to clear brush and thin the forest, they can harm or destroy ceremonial trails, archaeological sites, and other important tribal resources.

Bill Tripp, a member of the Karuk Tribe and head of natural resources and environmental policy, has witnessed bulldozers destroying a mushroom patch that has been used by the tribe for generations, causing it to stop growing in that area.

Now, the Karuk Tribe makes sure to have tribe members accompany fire crews on the lines in order to protect culturally important resources.

The strategy was put into place during last summer’s Six Rivers National Forest Lightning Complex Fires. After a series of lightning strikes started multiple fires across the Six Rivers National Forest and Redwood National and State Parks in August, a period of rain allowed land managers to let the fires burn on and to start some fires of their own.

Using designated lines to find suitable ridgelines, fire crews, accompanied by cultural representatives, started fires that moved downhill to merge with the wildfires. These controlled ignitions burned areas that the wildfires could have eventually reached, but likely did so in a more gentle manner. Taking advantage of natural fire behavior, the set fires mostly burned at low or moderate intensity, clearing ground-level vegetation.

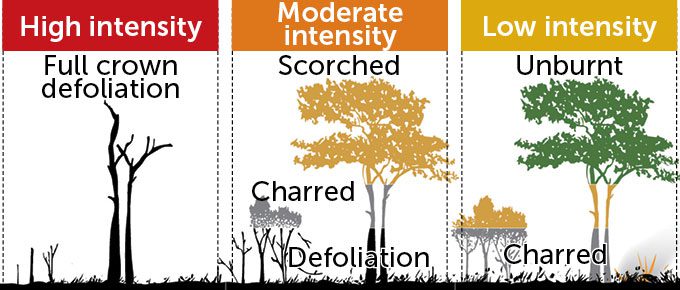

A low-intensity fire stays near the ground and mainly removes low-lying vegetation while sparing taller trees. On the other hand, a high-intensity fire can climb into tree canopies and cause the complete loss of leaves and needles. However, the absence of low-lying vegetation can slow down or even prevent these destructive fires.

GRID-Arendal/Studio Atlantis/Flickr (

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED

Fire scale

GRID-Arendal/Studio Atlantis/Flickr (

Science Advances , with the effects lasting at least six years.Even though the deliberately set fires burned within 100 meters of Harling’s home, he felt that the risk was worth it. “After 20 years of community work with the Karuk Tribe and partners, the federal agencies finally allowed us to use beneficial fire on the landscape,” he says. Tripp says that tribal consultations should be included in the process of treating lands within a POD. Merely opening the door for these discussions will highlight the need to build relationships, he says.In the 2023 Tribal Action Plan, the Forest Service emphasizes how important it is to appoint a tribal liaison for every wildfire response. Tripp suggests that using PODs might help identify where these liaisons could be most effective. If a POD is created in an area where there is no existing framework for working with a local tribe, that could be a reason to bring on a liaison to develop a relationship.

A new way to talk about wildfire

Go to the very middle of Arizona, and you'll likely end up near Payson. The town is surrounded by the Tonto National Forest, which is home to the largest continuous stand of ponderosa pine trees in the world. Some of those rough-barked, drooping-needled trees can be seen from Lata’s office.

“We know that this area used to burn approximately every seven years,” Lata says, referring to the time before widespread fire suppression began. As long as people are in the area, that frequency of fires is unlikely to return. “There aren't going to be many places where we allow the natural fire cycle to play its role, because even though we now understand how important fire is … we don't have the freedom to reintroduce that much fire into the system,” she says. There's a limit to how much fire and smoke people will accept.

During the Six Rivers National Forest Lightning Complex Fires in 2023, fire crews intentionally ignited fires to reduce damage from naturally occurring wildfires. In this photo, firefighters set fire to brush with a drip torch to prevent a blaze that posed a threat to a home.

Even so, PODs should help increase the amount of fire on the land, not only through the management of naturally occurring fires. Managers of the Tonto forest use PODs to pinpoint areas that would benefit from controlled burning to clear brush, thereby enhancing wildlife habitat, lowering the risk of wildfires, or obtaining other ecological benefits.

“It's obvious to use the PODs as boundaries for those projects,” Lata says.

Having a tool that can demonstrate to landowners why their neighbors’ property should be treated first is beneficial, says forest sciences researcher Cole Buettner of Colorado State University. In a 2023 study, he examined how PODs have been used in these non-incident contexts, as they’re called. “It can help generate a lot of support for what you’re doing.”

Perhaps in this respect, PODs fulfill their most crucial function. By translating ideas for fire into lines and colors on a map, PODs become a shared language through which a new relationship with wildfire can be established.

These shapes simplify the conversation, Lata says. “We can just say POD, and we all know what that means.”

Land managers in the western United States are using potential operational delineations, or PODS, to get ready for — and benefit from — wildfires.

Perhaps in this regard, PODs serve their most vital function. In translating visions for fire into lines and colors on a map, PODs become a communal language through which a new relationship with wildfire may be forged.

These polygons simplify the conversation, Lata says. “We can just say POD, and we all know what that means.”