TThe underwater mountains of the Nazca and Salas y Gómez ridges are a unique world. They stretch for 1,800 miles along the coast of Peru and are separated from the surrounding areas by a large low-oxygen zone, the depths of the Atacama Trench, and the powerful Humboldt Current. This isolation allowed evolution to take its own path.

Javier Sellanes, a marine ecologist at Chile’s Universidad Católica del Norte, says almost half of the species there live nowhere else.

Until recently, researchers had only studied the upper parts of the region’s seamounts. The creatures and communities living farther down their slopes were mostly unstudied.

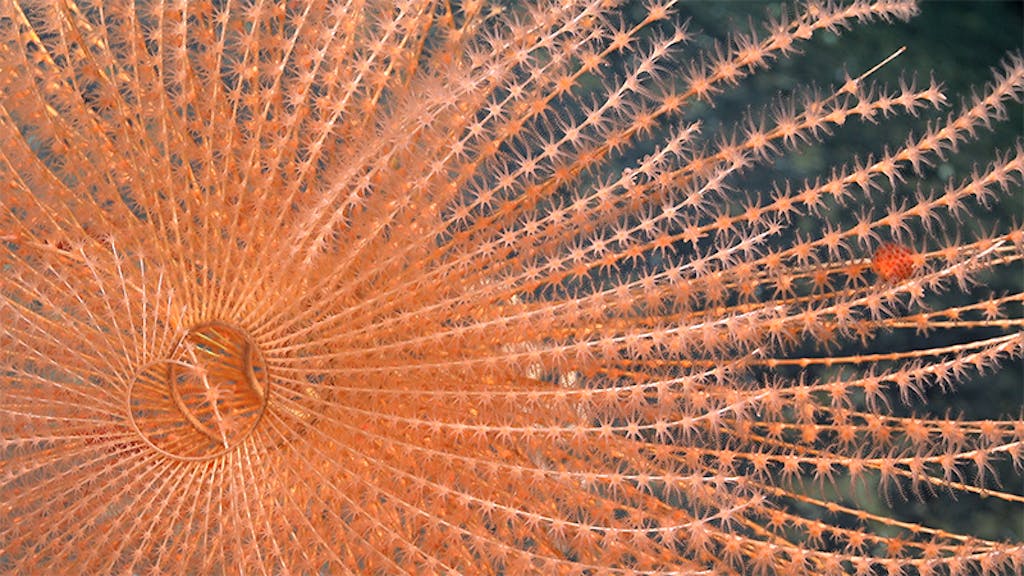

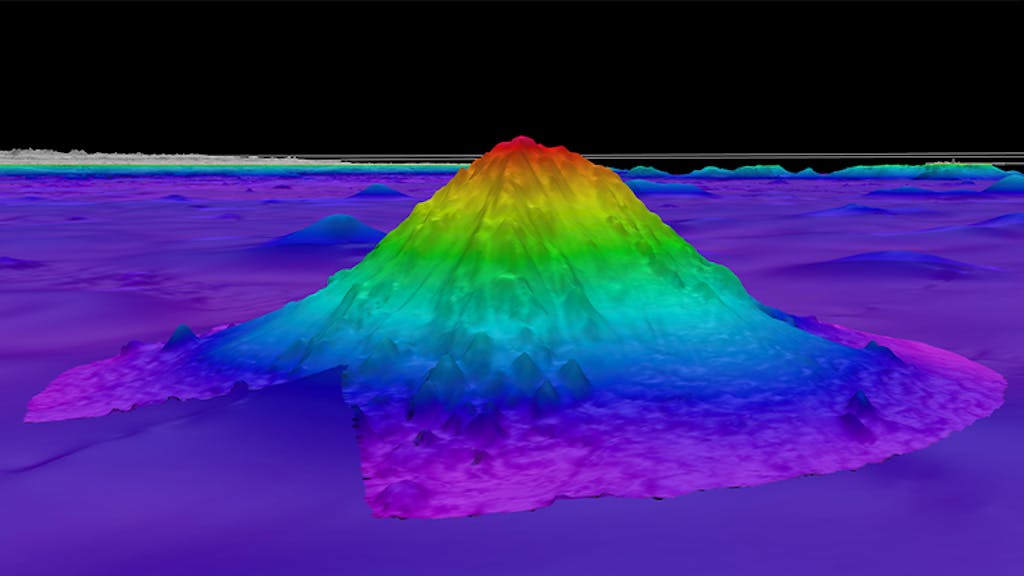

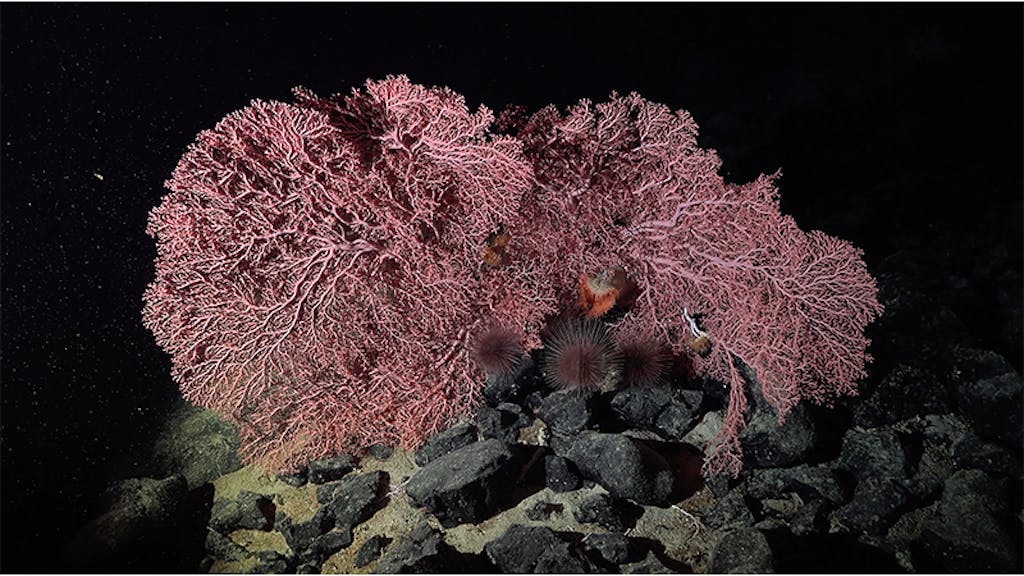

To find out more, Sellanes and a team of scientists went out earlier this year aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Falkor research vessel, equipped with a remotely operated submersible and all the instrumentation they needed to explore the depths. After mapping over 20,000 square miles of seafloor and discovering four seamounts, the researchers found a deep-sea wonderland: ancient corals, large urchins, fish adapted for walking, and over 100 species believed to be new to science.

Sellanes calls this “one of the least-explored areas of the ocean” and believes there is much more to discover at depth as at the surface.

TThe extraordinary communities observed by the researchers are thousands of feet below the ocean’s surface, yet their lives are closely linked to, and threatened by, events above.

Lost or discarded fishing gear eventually falls to the seafloor and trawling can destroy habitats that took millennia to form in a few hours. Seabed mining might bring not only localized destruction but also long-distance pollution through noise and sediment. Climate change affects the temperature and composition of deep-sea waters.

Sellanes hopes that the data collected on his journey will eventually be used to better control and safeguard the underwater mountains of the southeast Pacific. Doing so can be important for humans, notes Sellanes: Important fisheries may rely on species whose life cycles are connected to these underwater mountain communities. But, of course, the argument is not just about usefulness.

“Many of these species have small ranges. They’re unique to the region,” Easton mentions. “If they disappear, how will they be replaced?”

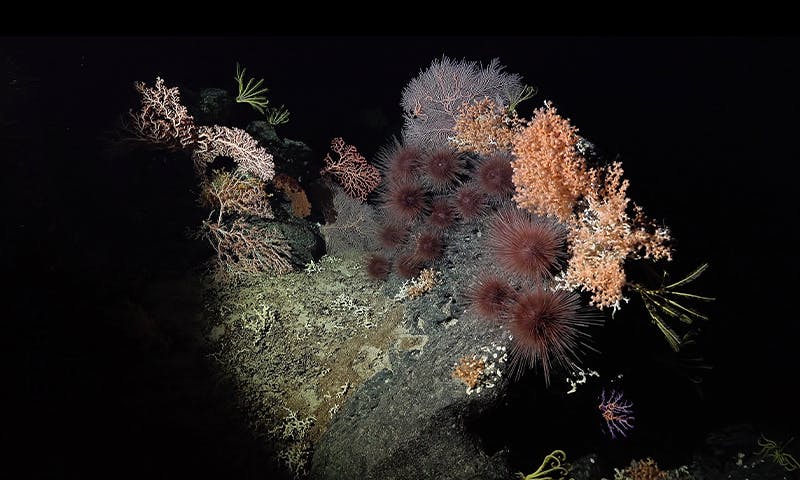

Lead photo: The submersible’s beams illuminate several types of corals. Their bodies offer homes and protection for many other creatures, including these cactus urchins, and their colonies are the basis of entire underwater mountain communities. Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute.