This piece is part of a series of Nautilus conversations with artists, you can find the rest here.

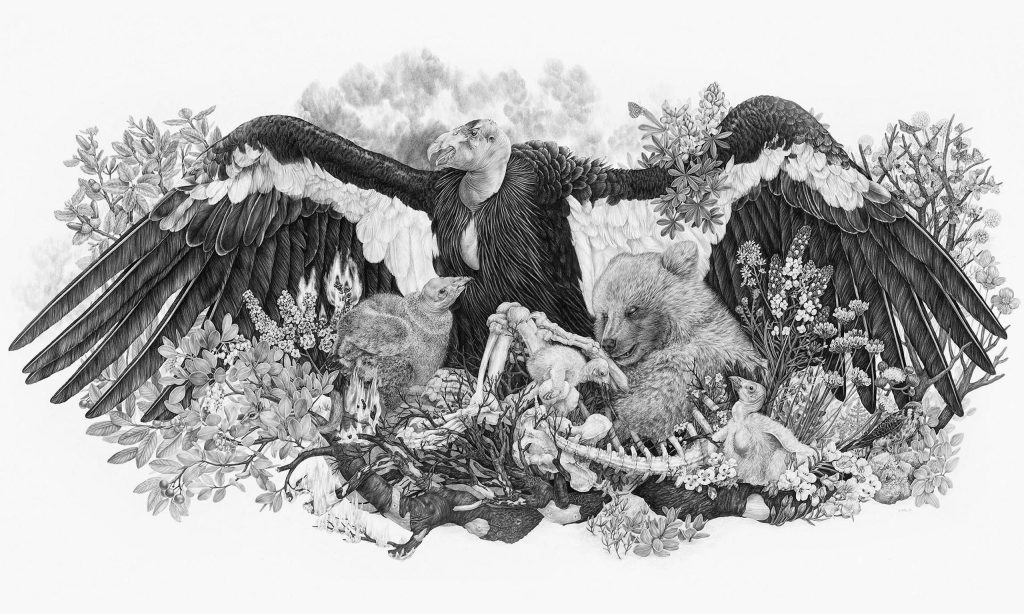

Zoe Keller is an artist with a mission to capture the beauty of biodiversity before it's too late. She works with both pencils and digital tools to carefully bring animals to life with a respect reminiscent of the great naturalists of the 19th century. Instead of documenting newly discovered species, Keller focuses on celebrating those at risk of disappearing.

This is one of the reasons why Keller was the perfect choice to create the cover for our first special edition about the ocean as well as the cover story for Nautilus Issue 39 about the decline in nautilus populations. We recently spoke with her to learn about her creative process, the difficulties of portraying endangered wildlife, and what scientists can learn from artists.

When did you decide to pursue art as your path?

I've loved drawing since I was very young, and I'm fortunate to have a supportive family. My interest in scientific illustration developed a couple of years after I graduated from college with a degree in Graphic Design, while volunteering with a group of artists on the coast of northern Maine. Over the past ten years, I've enjoyed using drawing as a tool to discover more about the natural world.

Your work is incredibly realistic and you capture even the tiniest details of the animals you depict. Can you tell us about your creative process?

I like to start with a loose plan, mapping out the entire drawing and refining the composition as much as possible. I work on the entire piece for some time to ensure I understand where the darkest values will be. The final stage takes the longest. I usually start from the top left corner and work my way to the bottom right, adding in the textural details. It's crucial for me to keep an eye on the piece as a whole as I work, ensuring that all the elements remain balanced.

Your work often showcases endangered or threatened species. Does an animal's conservation status impact how you portray it?

I'm particularly drawn to at-risk species that are less popular, such as snakes, amphibians, invertebrates, bats, and fungi, which are prominently featured in my work. I strive to depict these imperiled species in unique ways that may allow the viewer to appreciate the species' physical beauty for the first time. Additionally, I make an effort to emphasize the vital roles these species play within their habitats.

You mentioned reading primary scientific research when preparing for your projects. How does that influence the final product?

Reading about species is honestly my favorite part of the entire process! I love delving deeper into my understanding of a familiar species or living vicariously through a scientist who has studied a species I will never see in person. The more complex compositions in my work highlight species' life cycles, predator-prey relationships, symbiotic relationships, and mating rituals: aspects that are not obvious to me as a novice naturalist. Often, my initial concept for a piece will completely change after I've had the chance to go through a few journal articles.

A lot of your work, including the cover for the first Ocean Special Edition, Nautilus Ocean Special Edition, feature a variety of octopuses. What is it about these animals that captures your imagination?

This piece was originally made as part of an ongoing collaboration with PangeaSeed Foundation, to celebrate the diversity of our oceans and World Octopus Day. This piece showcases 10 of the almost 300 known species of octopus that live in waters worldwide. I enjoy exploring the differences between species: the delicate transparency of one, the bold, vibrant patterns on another. The more we look, the stranger, more beautiful, and more valuable our world becomes. I hope that art can help protect what has not already been lost during our human-driven mass extinction era.

Is there anything you think scientists can learn from artists—or vice versa?

Every scientist I've met seems like an artist to me. We're all similar! I believe that scientists and artists working together can be very effective storytelling teams: Scientists provide the knowledge, and artists can help translate that information into compelling visuals.

The emergence of generative AI services like Midjourney is causing some controversy in the art world. What are your thoughts on the use of AI to create art?

Living artists are already feeling the impact of AI. AI-generated art is appearing on the covers of popular authors, in advertisements from big companies, and on the clothing of well-known brands, among other instances I know of. These companies have the means to pay artists, but they choose not to. For many smaller and mid-size companies, paying artists is a challenge. As AI continues to advance, the temptation to take shortcuts with AI will be huge. Making a living as an artist is incredibly difficult, which is why many successful people in the art world come from privileged backgrounds.

I grew up middle-class with no connections in the art world, and worked hard to establish a full-time, self-employed creative career by piecing together various gigs and jobs, often from small companies for low pay. Over time, the gigs improved, the clients became larger, and the pay increased. Looking ahead, I believe that many of those entry-level jobs—the jobs that helped launch my career—will not be available to the next generation of artists. They will be done by AI. There will always be artists, but if AI art becomes normal, I'm concerned that the already small portion of the art world consisting of working and middle-class artists will be devastated.

You have an extensive collection of nature guides; do you have any must-have recommendations for our readers?

I love Peterson Field Guides for reptiles and amphibians and Sibley Guides for birds. National Audubon Society Field Guides are another go-to for species of all kinds. I always look for region-specific guides when I’m traveling. Park gift shops and small local book stores often stock books and guides that can be difficult to find online, or that are so specific you might not even think to search for them!

Are there any upcoming projects that you are enthusiastic about?

I recently returned to the mid-Hudson Valley in New York and am very excited to start working on a significant personal project. A group called ‘Zena Development LLC’ has recently bought 625 acres of untouched forest in my hometown of Woodstock, New York. I plan to showcase the variety of plants and animals and the natural attractiveness of this area, in order to support the volunteers who are resisting the developers’ plans.

Interview by Jake Currie.

Lead image courtesy of Zoe Keller.