A separate investigation of a priest accused of sexually harming Inuit children in Nunavut states his Catholic group didn't know about the claims when he went back to France.

A retired judge named André Denis conducted the analysis of 93-year-old Johannes Rivoire.

Denis discovered that the Oblates of Mary Immaculate were not aware that Rivoire was under investigation by Canadian police when he returned to France in 1993, and the religious group was not contacted by RCMP when charges were made five years later.

The investigation reveals that the Oblates in France only learned of the charges through a news report in 2013.

“Rivoire did not fully tell the truth to his superiors, to his fellow priests, to the Inuit under his care, and he himself denies a reality that has been proven,” Denis stated in his final report released Tuesday.

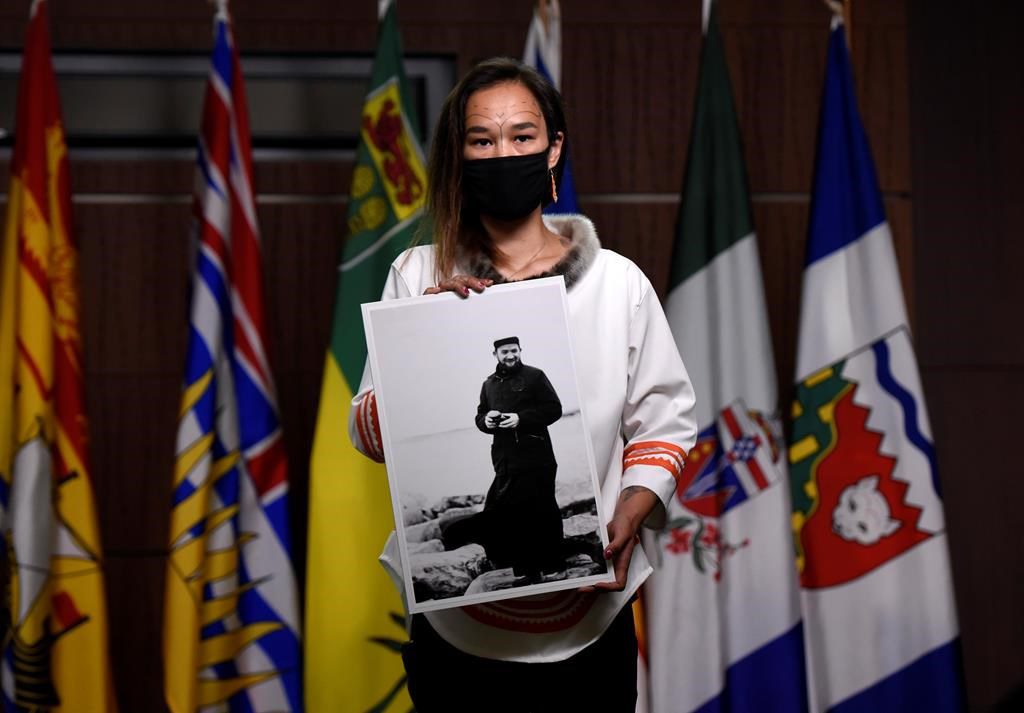

Rivoire declined to come back to Canada after an arrest warrant was issued in 1998. He was faced with at least three charges of sexual abuse in the Nunavut communities of Arviat, Rankin Inlet, and Naujaat. More than two decades later, the charges were dropped.

Another arrest warrant was issued for Rivoire in 2022 for a charge of indecent assault involving a girl in Arviat and Whale Cove between 1974 and 1979. French authorities rejected an extradition request.

Inuit leaders and politicians urged the priest to stand trial, and there was increasing pressure on the religious group to provide explanations.

Last year, Denis was appointed by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, OMI Lacombe Canada, and the Oblates of the Province of France to lead the review.

In 2020, Denis was also requested by the Archdiocese of Montreal to review accusations of sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults in nine Catholic dioceses in Quebec. Additionally, Pope Francis assigned Denis earlier this month to investigate allegations against a senior leader of the Roman Catholic Church in the province.

Denis stated that his findings on Rivoire do not serve as a replacement for a trial. However, based on the “preponderance of evidence,” the review supports claims that Rivoire assaulted six children in Nunavut.

The investigation also uncovered evidence of another Inuit victim around 1968 to 1970, despite no formal complaint being filed.

Rivoire has denied all accusations against him, and none have been proven in court.

When the Oblates in France confronted Rivoire 15 years after the charges were filed, the report states that he told another priest in France that he is “not innocent” and “in the (Inuit) environment children were looking for tenderness that they didn’t have in their families.”

The report alleges that Rivoire said, “If I’m not innocent, the children aren’t either, but we don’t say that.”

Denis met with Rivoire in France last year. The priest maintained his innocence, the report states, but he admitted to having a sexual relationship with a woman.

Rivoire arrived in Canada in 1959 and stayed in the North until January 1993, when he informed superiors that he needed to return to France to care for his elderly parents.

In that same month, four individuals went to the RCMP in Nunavut to accuse Rivoire of sexual attacks.

Denis suggests that maybe the priest left because of rumors about his behavior, but the church was not informed about this.

Denis talked to some of the people who complained and to family members of those who have passed away. They discussed the ongoing trauma and pain they experienced.

Many people believed that the Oblates were involved in Rivoire’s departure, as stated in the report.

Denis examined extensive records from the Oblates in Canada, France, and Rome.

He also spoke with church officials from that time. He found no proof that the church knew about the accusations or played a part in assisting Rivoire in leaving.

The report states that neither the 1998 charges nor the arrest warrant were given to Rivoire or the Oblates, and the case was not made public due to a publication ban.

The next year, the RCMP informed a northern diocese of an investigation and provided contact information for Rivoire in France.

The report states, “The RCMP had no communication with the Oblates, nor did they notify them of anything throughout the legal process.

When the Oblates found out about the criminal proceedings in Canada, Rivoire was not allowed to publicly minister. The Oblates in Canada and France repeatedly encouraged Rivoire to face the charges, but he refused.

The Oblates in Canada and France also appealed to leaders in Rome to start the dismissal proceedings against Rivoire, but earlier this year it was decided that the priest could remain a member of the congregation.

Denis urges the superior general in Rome to reconsider that decision, the report says. This may not provide the justice Inuit families seek, but it could bring some healing.

The report says, “A symbolic measure but a balm for the victims’ wounds. Perhaps the only one.”

Rev. Ken Thorson of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate Lacombe Canada said that nothing can undo the harm and tragic history of clerical abuse.

In a news release, Thorson said, “We hope this report offers some validation for those who were silenced and disregarded many times by various institutions and authority figures across this country.