Sports are a human universal, found in every known culture. We can hardly imagine England without cricket or the United States without baseball, basketball, and football. Japan without sumo wrestlers is no longer Japan.

Cultural change is another human universal. Over the millennia, cultures have emerged, flourished, declined, and disappeared. This cultural ebb and flow raises a question. What happens to a culture’s sports if that culture disappears? The answer is deceptively simple. When the culture disappears, its sports vanish.

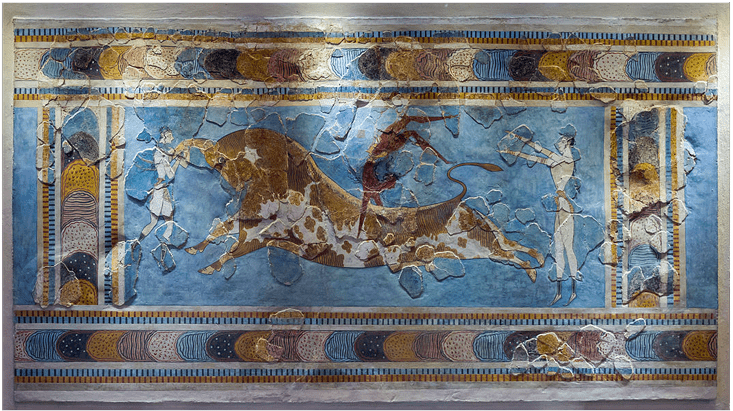

So it was with the Minoan culture of ancient Crete. In a damaged, hard-to-interpret fresco found in the Palace of Knossos in the town of Heraklion, girls (painted white) boldly grip the horns of a huge bull or wait to catch the boy (painted red) who is in flight over the bull’s elongated back. It is possible that the painted figures represent acrobats performing for the amusement of the court, but it is more likely that their sport was part of an intiatory ordeal or a fertility ritual. We cannot be sure because the palace is a ruin and the sport vanished millennia ago.

And so it was with the vanished Aztec culture of pre-conquistador Mexico. In areas adjacent to their temples, young men engaged in a ball game, known as ōllamaliztli, that concluded with the bloody sacrifice of one of the players upon the temple’s altar. Whether the sacrificed player was a winner or a loser we shall never know. The temples are in ruins and the game has vanished, condemned as satanic by the Christian conquerors.

Aristotle would have categorized this modern mania for price quantification as a psychic disorder.

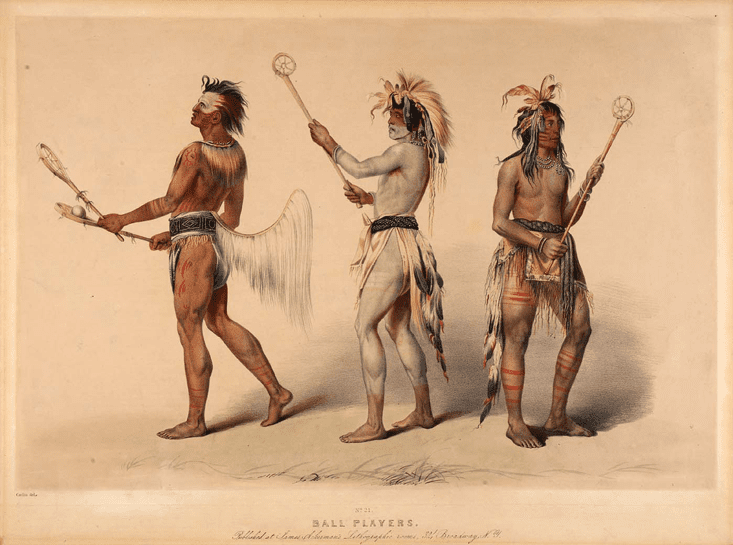

Cherokee stickball, another traditional sport associated with religious ritual, seems to be an exception to the rule. It seems, at first glance, to have survived the assimilated culture in which it was an integral part. The traditional game began with 28 days of sexual abstinence. The night before the game, shamans scarified the players (all male) on their arms, legs, backs, and chests. Each player bled from nearly 300 gashes. The game itself took place on a field whose boundaries were not strictly defined; the goals might be 100 feet or several miles apart. The number of players varied from 20 to several hundred on a side, and the two sides were not necessarily even. The player used a pair of sticks to carry and throw a ball—and to hit their opponents. (Serious injuries were common.) Cherokee stickball is still played, but it has been transformed and packaged as a tourist attraction. The field is now a rectangular space similar to the playing fields of soccer, rugby, and American football. The two teams are now equal in the number of players and—most importantly—the game has been stripped entirely of its religious aspects. Medicine men roam along the sidelines, but no one pays much attention to them. Lacrosse descends from the Eastern version of stickball, but it, too, is substantially different from its ancestral game.

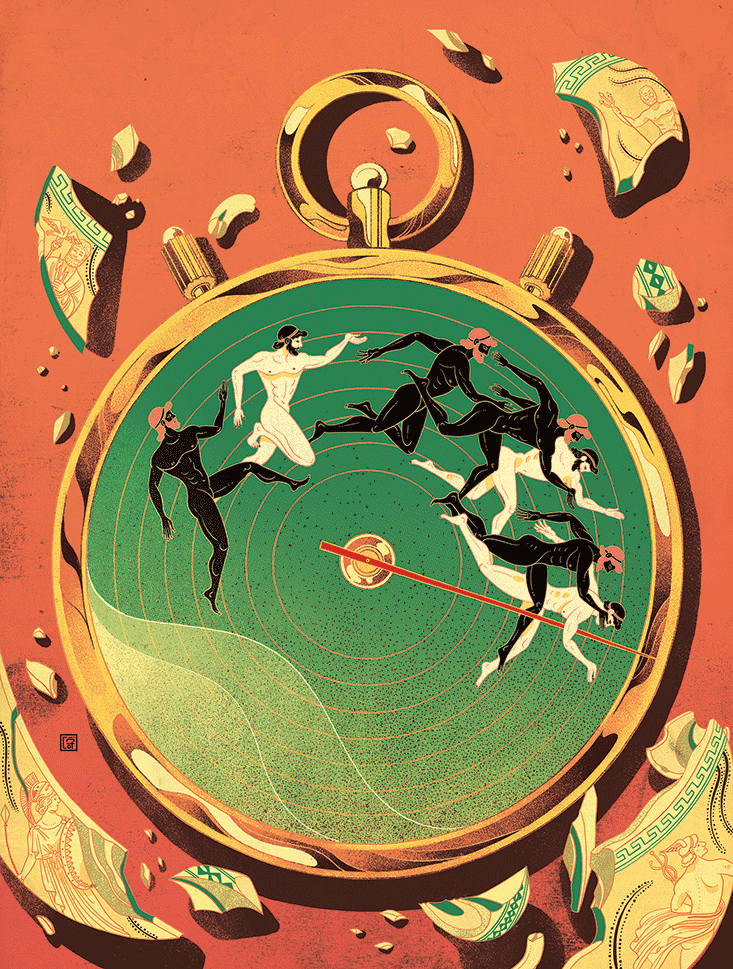

The Olympics are yet another example of a reinvention so thorough that the original sport is played in name only. Ancient Greek culture did not vanish as did the cultures of Minoan Crete and pre-conquistador Mexico. Indeed, much of what the Greeks achieved is still with us. But the ancient Olympic Games did vanish. They were forbidden after the Roman Empire’s conversion from paganism to Christianity in the fourth century.

They were supposedly revived in 1896 by Pierre de Coubertin, a philhellenic French aristocrat, but the modern Olympics have almost nothing in common with the ancient games other than the name and the fact that they are celebrated every four years. As a pious gesture, Coubertin added the discus to the track-and-field program, but none of the athletes, not even the Greeks, knew how to throw a discus.

We can best understand the fundamental difference between the ancient and the modern Olympics if we look at what is arguably the simplest and most widely practiced of all sports: foot races. The quadrennial athletic festival celebrated in honor of Zeus, at Olympia, began (in the eighth century B.C.) with a single foot race. In time, a number of other foot races were added to the program, but never as many as at the modern games. The ancient runners had to be ethnically Greek free adult males. No slaves and no foreigners were allowed to compete. Women were barred from the site even as spectators. (Girls had their own races, at a separate festival in honor of Hera.) In the heyday of the ancient games, the athletes competed entirely nude, presumably in order to emphasize the fact that the Olympics were a sacred religious festival and not a part of everyday life. The races were not timed. The Greeks lacked the technological ability to accurately time a race. The Greeks did measure distances, but the unit of measurement for foot races was far from standardized. It was the stade, that is, the length of the stadium. The stade was the unit of measurement for all Greek athletic festivals, but the length of the stade varied from one athletic festival to the other because the size of the stadium varied from festival to festival.

At Olympia, the shortest race was one stade. The diaulos or “double race” was twice as long. Contestants raced to a marker at the far end of the stadium, rounded it, and then raced back to the starting line, which consisted of stones set in the sand. In the dolichos, the longest of the ancient races, the runners ran back and forth many times. How many times, no one knows for certain.

Coubertin meant his renovation of the ancient Olympics to become a secular religion with an array of invented rituals.

And the men’s and women’s foot races at today’s Olympic Games? The runners, representing some 200 different nations, are racially, ethnically, and religiously diverse. None, to the best of my knowledge, is a slave—except to the nearly incredible demands of modern scientific training. In order to compete, ancient Olympians had to pass scrutiny by religious authorities known as hellanodikai. Modern Olympians become eligible when they are selected by National Olympic Committees that have been officially recognized by the International Olympic Committee. The runners, who are most definitely not naked, wear spiked shoes scientifically designed to maximize performance. The length of the race is measured in meters, which are defined as the distance traveled by light in a specific fraction of a second. The standardized 400-meter track measures 84.39 meters for the straights and 115.611 meters for the curves. Each lane is 1.22 meters wide. The starting blocks, which are not blocks, are electronic devices that make it utterly impossible for a runner to successfully “jump the gun. ” Races are timed to the hundreths of a second. Aristotle, who compiled a list of ancient Olympic victors, would have categorized this modern mania for price quantification as a psychic disorder.

The hurdles, which were never a part of the ancient games, are an even more striking example of standardization and quantification. For the men’s 110-meter hurdles, each obstacle is exactly 1.067 meters high. The distance to the first hurdle is 13 meters, the distance between the intermediary hurdles is 8.5 meters, and the distance from the last hurdle to the finish line is 10.5 meters. The hurdle itself is an abstract, standardized version of the highly irregular fences and hedges over which premodern runners leaped.

The price of ludic (from the Latin ludus, game) survival is secularization, standardization, and quantification. Modern sports have lost the religious dimension that pervaded ancient games. People may pray to play, but no longer play to pray: The game no longer fulfills a specific religious function. In the modern commercialized world, sports—even Olympic sports—are more likely to serve Mammon than God. And yet the human impulses found in traditional religion have made their way into even the most secular sports. With their innumerable rituals, their expressions of faith, their idolatrous worship of “immortal” stars, and their sagas of a fall from grace followed (of course) by a deeply moving redemption, sports events are probably the closest that any secular activity can come to a religious ceremony. Although sports may no longer serve religion, they arguably are a religion.

There is a church in Argentina called Iglesia Maradoniana. In this church, God is football—soccer—and its prophet is the renowned player Diego Armando Maradona. Founded in 1998, the year after the star’s retirement, the Iglesia Maradoniana now has some 120,000 members worldwide, who bear its insignia D10S—a portmanteau of Dios, the Spanish word for God, and Maradona’s shirt number, 10. Members congregate in sports bars; transubstantiation occurs not to wine and wafer, but to beer and pizza. They even have their own version of the Lord’s Prayer: “Our Diego, who art on the pitches, hallowed be thy left hand,” alluding to Maradona’s controversial “hand of God” goal in the 1986 World Cup.

It all sounds a bit absurd, but at least some of the church’s founders and followers appear to be serious. Co-founder Hernán Amez told The Argentina Independent in 2008: “It’s not just a bit of fun—it’s a religion. Religion is about feelings, and we feel football.” He is right, psychologically speaking. The power of religion, sociologist Émile Durkheim wrote, stems from its ability to unite two of our deepest yearnings—the universality of God and the cultural specificity of a clan—through totems and rituals. The specific beliefs of a religion do not matter so much as its ability to meet these emotional and social needs. In other words: deed, then creed. Given this, Iglesia Maradoniana seems entirely logical. Ninety percent of Argentinians declare allegiance to a soccer team, and more than 2.5 million play the sport in a structured capacity. Soccer was already a religion in Argentina.

While we commonly think that ancient sporting rituals were performed in the service of religion, this modern example and others suggest it is just as often the other way around: Religion adapts itself to sport. Take the United States, where football (American football) and faith are closely linked. Football counts 63 percent of Americans as fans, more than any other sport in the country. Fully half of American sports fans tell pollsters they believe God influences the outcome of games. One-fifth perform some kind of ritual before or during games of their favorite teams, whether that’s wearing color-coordinated clothing (e.g., the green and gold of the Green Bay Packers) or team symbols (the Packers’ cheese-shaped hats, jerseys), sitting in the same seat for each game, or turning their underwear inside out. For some people, sports seem to be replacing religion. On the average Sunday, 21 percent of Americans say they are more likely to be watching football than attending church.

“The relationship between sports and religion in America has always been close, and it has often been awkward,” Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote in 2014. Awkward for him, perhaps. If people can find God in a stadium just as easily as they can in a church, is traditional religion doomed?

Well, if a sport can become like a religion, a religion can become like a sport. Megachurches, defined as churches that have 2,000 or more in weekend attendance, are often modeled after sports stadiums. Crenshaw Christian Center in Los Angeles, perhaps the largest sanctuary in the U.S., can pack 10,400 churchgoers into its 360-degree stadium seating. Critics of megachurches argue that their large size discourages nuanced discussions of social-justice issues and the formation of intimate communities. What they do encourage is groupfeel. Sociologist Katie Corcoran has likened sitting in megachurch to standing in the crush of a packed stadium: Both allow the self to melt away.

Recognizing that this selflessness transcends any single belief system and, perhaps, sports’ superior ability to catalyze it, megachurches are now seeking to wield sports’ power for their own ends. In 2005 theologian Matthew Brian White examined the 100 largest megachurches to examine how they used sports to win over followers, a practice known as “sports evangelism.” In addition to distributing pamphlets and videos at major sporting events, megachurches have created their own sports associations such as Upward Basketball, which integrates religious practices into pre-game rituals and play. “In a gym full of parents, uncles, aunts, and grandparents, while the kids are off talking strategy, the adults are hearing about how to know Jesus,” White reports. John Garner, author of Recreation & Sports Ministry, writes: “If we are to reach this type of world, we must use every tool at our disposal to capture the imagination of this leisure-oriented, unseeded, and sports-crazy culture.”

Religion has proved itself adept in evolving with culture, and Iglesia Maradoniana is just one example. As Anthony Bale, a 23-year-old Scot who attended the Maradona Christmas celebration in 2008 at an Italian restaurant in the Argentinian city of Rosario, said: “What has Jesus done that Maradona hasn’t? They have both performed miracles. [It’s] just that Maradona’s are actually on record.”

—Susie Neilson

No one understood this better than Coubertin. He meant his renovation of the ancient Olympics to become a secular religion replete with an array of invented rituals—the parade of nations, the rings, the torch, the flame, the oath, and the medal ceremony with its flags and anthems. In the words of Avery Brundage, Coubertin’s American disciple, president of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972, the Olympics are “a 20th-century religion, a religion with universal appeal which incorporates all the basic values of other religions, a modern, exciting, virile, dynamic religion.”

That sports can become a secular religion is an insight shared by the leaders of Japan’s Sumo Association. Sumo, in fact, is a splendid example of a sport that did not vanish with its cultural context. One reason for the sport’s success has been the ability of its governing association to modernize the sport’s practices. The Sumo Association standardized the ring and strictly regulated the amount of time allotted to shikiri (ritualized, precontact staring and stamping). The association rationalized its traditional ranking system to allow promotion on the basis of quantified achievement and reluctantly opened the very top rank, the yokozuna, to ethnically non-Japanese wrestlers.

In other words, the Sumo Association behaved like other sports organizations engaging with the processes of modernization. But sumo was different from most other traditional sports in that its leaders quite consciously embarked on a process of retraditionalization. They took a sport that had begun to modernize and introduced “traditional” elements that were actually not at all traditional. In its origins, sumo seems to have been a wholly secular sport, practiced at the imperial court as a form of political rather than religious representation. Today, ritual purification of the ring in accordance with Shinto custom is a prominent part of the spectacle. In 1909, the referee was stripped of his modern garb and anachronistically attired in garb similar to that of a Shinto priest. In 1931, the farmhouse roof above the sumo ring was redesigned to conform to the architectural style of the sacred Shinto shrine at Ise. Thanks in part to this combination of modernization and retraditionalization, sumo has not vanished; it has simply played fast and loose with past and present.

Sumo’s success can be contrasted to kemari’s failure. Kemari, a medieval Japanese football game, was played in a more or less rectangular space at whose four corners were planted cherry, maple, pine, and willow trees. Players kicked a deerskin ball cooperatively in order to keep it aloft as long as possible, like hackysack. The physical grace of the elegantly attired players mattered far more than the number of successful kicks. There were no winners and no losers. In 1884, as Japan was beginning its drive to modernize, a group of aristocrats created a society to preserve the game in its pristine form. Their success was limited. As a spectator sport, sumo holds its own with Japanese baseball. Kemari is performed on a few temple grounds as an annual festival attracting a small group of curious tourists.

When cultures disappear, their sports disappear with them. When cultures are transformed, either from within or in response to external forces, their sports are also transformed—and only a few of us spend much time pondering the nature and extent of the transformation.

Allen Guttmann is a professor of English and American studies at Amherst College. He has written numerous books, including The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games and From Ritual to Record.