George Shiras the third (1859-1942) was captivated by the waters of Lake Superior at night, when sounds, shapes, and movements seemed more mysterious, more dramatic. Under cover of darkness, he sought out animals that lived along the shore of the lake. Shiras would place a lamp at the bow of a canoe and wait quietly in the shadows at the rear of the boat, until two eyes could be seen reflecting the boat’s light back out of the darkness. The “blue, translucent eyeballs” were the signal to quietly slide forward into range, take aim, and shoot his quarry. This was how Shiras took the first photos to show the nightlives of wild animals, over a century ago.

[NB:slide]

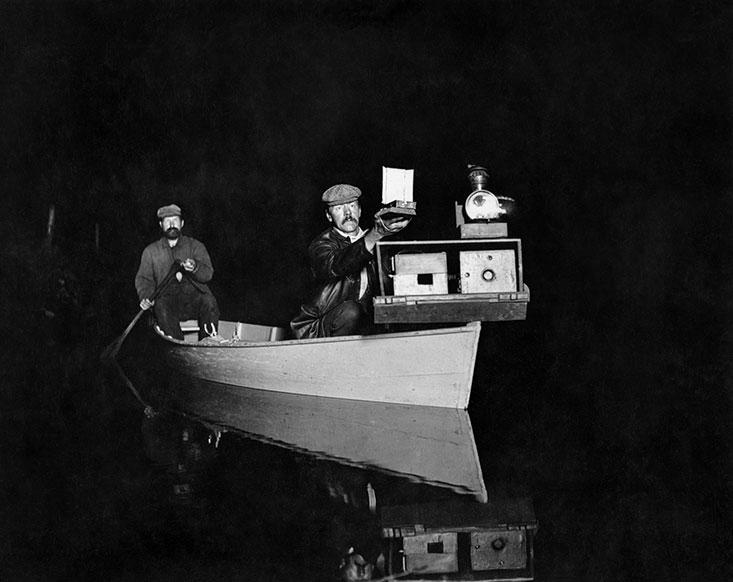

In these early days of photography, Shiras was forced to haul clunky cameras using large-format sheet film on his canoe; the flash was an explosion of magnesium powder that he likened to a mystifying “blowing moon.” Shiras described what happened at this critical moment: “Suddenly there is a click and a white wave of light breaks out from the bow of the boat—deer, hills, trees, everything stands out for a moment in the white glare of noonday. A dull report, and then an inky veil of darkness descends. Just a twenty-fifth of a second has elapsed, but it has been long enough to trace the picture of the deer on the plates of the cameras, and long enough to blind for the moment the eyes of both deer and men.”

Confused or scared animals would sometimes charge the boat, knocking cameras overboard. Sometimes he used two cameras, one to capture the animal as it quietly watched the light, and another to catch the animal in flight after the first flash. Shiras adapted the flash and camera setup over time, by trial and error.

Shiras’ photographic technique was an adapted form of “jacklighting,” a hunting practice he had learned from guides belonging to the Ojibwe tribe of Native Americans. Between Shiras’s groundbreaking pictures and the articles he wrote about “hunting with a camera” for various publications in the 1890s, he was instrumental in popularizing wildlife photography. Shiras later served in Congress, where he sponsored the first bill meant to protect migratory birds.

A new book, George Shiras: In the Heart of the Dark Night, rediscovers photographs from his night prowls, presenting them for the first time in a monograph. Perhaps what makes these images seem so fresh even now is the relative lack of compositional control in the experimental process. The animals are transfixed by the boat’s light—sometimes they pause in their nocturnal routines to stare, other times they turn and run. The images are documentation of an intervention, records of human and animal interaction. What we see is not nature as it is, or nature idealized, but rather nature observed.

Rebecca Horne is a California-born, Brooklyn-based artist, writer, and multimedia producer.

All photography © National Geographic Creative Archives. Distributed in the U.S. by Dap, available on www.Exb.Fr