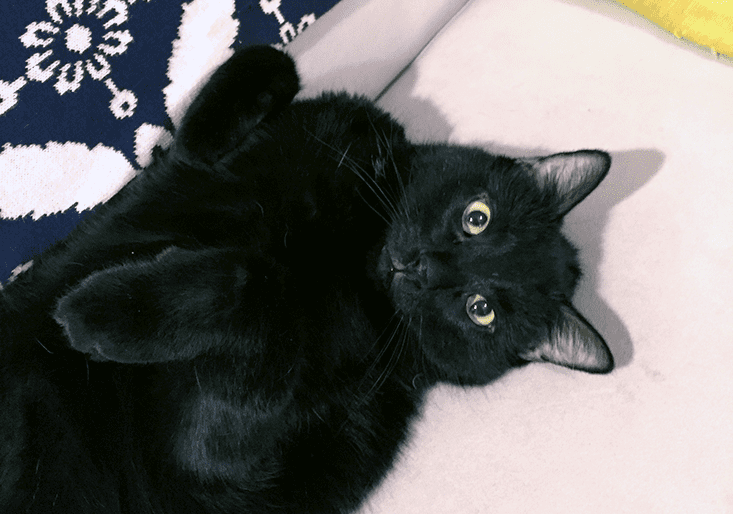

When I first adopted Lucas nine years ago from a cat rescue organization in Washington, D.C., his name was Puck. “Because he’s mischievous,” his foster mother said. Although we changed the name, her analysis proved correct. Unlike his brother Tip, whom I also adopted, a gray cat with white paws and an Eeyore-ish dour doofy sweetness, Lucas was from the start a fierce black fireball, a menace to stray toes or blanket fringes or loose items on tabletops. He was my alarm clock in the morning with his habit of knocking my hairbrush, deodorant, and earrings box off my bureau until I got up to feed him.

Then, almost four years ago, my husband and I had a child. Lucas, no longer the most important small creature in the apartment, retreated to the top shelf of his cat tree, where he would lie all day, staring morosely over the edge. When he did want attention, his solicitations became aggressive. Instead of waiting until 7 a.m. to start knocking things off of the bureau, he started hopping up there at 4 a.m. We closed the bedroom door and were still woken up at 4 every day by Lucas rattling the doorknob or hurling the weight of his 13-pound body against it. At mealtimes he would gobble down his food and then shove Tip out of the way to eat Tip’s food. He started marking the carpets in our living room and my son’s room, and his play with Tip turned more violent too.

I made an appointment, first, with a pet behavior specialist and, five months later, when her initially helpful suggestions didn’t change Lucas’s behavior, with a vet. The vet described Lucas’s condition as “anxiety” and prescribed fluoxetine, a generic for Prozac that’s often prescribed for animals. While I had felt a mixture of frustration and pity toward Lucas, in that moment I experienced a surprising stir of recognition. Over a decade ago, during six months in college, I had panic attacks every other day. I was given a similar diagnosis—panic disorder being a major anxiety disorder—and was prescribed a similar medication.

More than 50 years ago, behaviorist B.F. Skinner wrote, “The ‘emotions’ are excellent examples of the fictional causes to which we commonly attribute behavior.” For animals, who can’t describe their own emotions in words, this sentiment has proved more enduring than it has for humans. My panic attacks were an anxiety ouroboros: Am I having an attack now, on the subway? How about now, in front of my English class? Oh shit! It’s hard to imagine a rat or a mouse—or even my brilliant cat—ruminating on that obsessive meta-level. As Kierkegaard wrote in The Concept of Anxiety, “anxiety is not found in the beast, precisely because by nature the beast is not qualified as spirit.”

In fact, the concept of animal anxiety is something science has been wrestling with for a long time. And while our definition of anxiety, when it comes to animals, may still be fuzzy, it is growing ever sharper with time. That process has taught us much about our own emotions, and continues to teach us more about animal cognition. In the end, it also taught me a lot about my relationship with Lucas.

With all or almost all animals, even with birds, Terror causes the body to tremble,” Darwin wrote in his 1872 book, The Expression of the Emotions in Animals and Man. Today, with a greater understanding of the subcortical basis of fear, we know how closely brain systems resemble each other across mammals.

When a threat occurs, the flight-or-flight response is triggered by the amygdala, then moves to the hypothalamus, which in turn sends a signal to the glands, releasing adrenaline. The same happens in most mammal brains: Mice have tiny hypothalami and amygdalae that react to stress just as ours do. And as any dog- or cat-owner knows, the manifestations of fight or flight in animals are plentiful, complex, sometimes patterned (a dog that always sucks its paws and yowls during thunderstorms), sometimes based on temperament or genetics, sometimes coming out of the blue—very much like human anxiety.

Giving human drugs to animals isn’t just species narcissism. We know these drugs work for animals because they were originally tested on animals.

Veterinary behaviorists don’t worry much about whether anxiety is a valid term for what animals experience, or how to diagnosis it. “It’s not terribly difficult,” says Katherine A. Houpt, an emeritus professor of behavioral medicine at Cornell University. Vets look at external display: Does an animal startle quickly, snap, suffer from sleeplessness? Is a cat in a fearful posture like something New Jersey behaviorist Emily Levine called “the meatloaf position” (all four legs under and hunched)? By these observable measures, anxiety exists in great quantities in the animal kingdom, both among pets and far beyond.

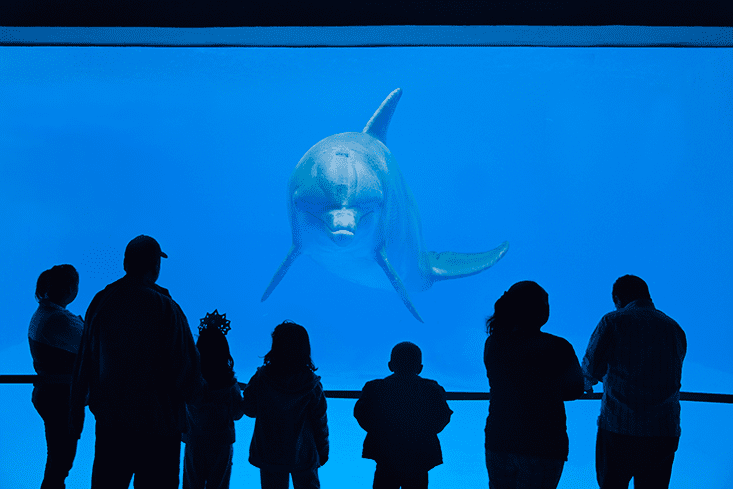

In her book, Animal Madness, science historian Laurel Braitman cites a study by the pharmaceutical giant, Eli Lilly and Company, that states that 17 percent of American dogs suffer from separation anxiety. Braitman also describes anxious zoo gorillas and a bonobo who wouldn’t eat a meal until he went through a series of obsessive compulsive disorder-like rituals, anxious chickens given Prozac to calm down so their flesh will be more delicious, and the “stereotypic” (repeated self-harming) and aggressive behavior of walruses and sea lions at amusement parks like SeaWorld.

To ease their symptoms, we’ve been giving animals our meds for decades. Starting in the 1970s, captive animals were increasingly medicated, ranging from Gus the bipolar polar bear to penguins bummed out by British weather to the sea mammals at SeaWorld, caught in a scandal in 2014 after court documents obtained by Buzzfeed showed that doctors were dosing aggressive orcas with benzodiazepines, the family of anti-anxiety medication that includes Xanax and Valium. Some of the mine-sniffing dogs in Afghanistan diagnosed with PTSD were given Xanax, as well as other treatments, like desensitization. So many dogs, cats, and other pets are on antidepressants and antianxiety medication today that the industry has swelled to a multibillion-dollar business.

Giving human drugs to animals isn’t just species narcissism. We know these drugs work for animals because they were originally tested on animals. The underlying similarity between mammalian brains and patterns of anxious and depressive behavior has allowed monkeys, dogs, cats, rats, and mice to stand in for humans in psychoactive drug testing starting with the early barbiturates in the 1900s and continuing through tranquilizers in the ’60s to today’s SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), drugs that, it’s believed, improve the symptoms of depression and anxiety by increasing levels of a neurotransmitter called serotonin.

Methods of provoking or measuring stress in laboratory animals to study these drugs are endless, creative, and should come with a trigger warning, if you’re at all an anxious person yourself. In the “forced swim test” (my summer-camp nightmare) mice are forced to swim in cylindrical pools to test their resilience in the face of certain defeat. Some “animal models of anxiety” try to create situations that are especially stressful for animals, like open spaces (the “elevated plus maze”) or being out in the open on a balance-beam like structure (the “Suok ‘ropewalking’ test”).

Methods of provoking stress in laboratory animals should come with a trigger warning, if you’re at all an anxious person yourself.

In one chronic stress experiment, mice were restrained, shaken, isolated, held under a hot hairdryer, kept under bright lights overnight, or had their cages tilted at a 45 degree angle. In the end—and just like humans who live under chronic stress—the mice became severely anxious and lost any appetite for “exploratory behavior,” like depressed teenagers hiding out in bed.

There’s plenty of debate over whether the stress tests and other “animal models of anxiety” match up closely enough to human anxiety to make all the animal research on psychoactive medications credible. Even the more subtle tests seem closer to repeatedly punching a human in the face until that human collapses into a shivering puddle, rather than replicating the complex patchwork of genetic and environmental factors that end up producing a human anxiety disorder.

Researchers rarely use the word anxiety to describe what the animals experience. Studies usually describe “anxiety-like symptoms,” focusing on the behavioral rather than the emotional, the expression of the feeling rather than the feeling itself. The fact that anti-anxiety medication soothes these symptoms in animals suggests they have something in common with the symptoms we call anxiety in humans. But are they a conditioned fear or something else entirely? And can we humans ever really know?

Joseph LeDoux, a professor of neural science and psychology at New York University, and author of The Emotional Brain, has performed some of the most important research on anxiety disorders. “Do animals have mental states? We don’t know, and we can never know for sure,” he said in an interview with BrainWorld magazine in 2012. For LeDoux, observations of behavior aren’t enough to give it a label like “anxiety” when we can’t enter into the animal’s subjective experience. It might be emotion, it might also just be an automatic response to danger, and without any way of entering into the animal’s brain—the way language allows us to, at least to a certain mediated degree, with other humans—we can’t assess that.

But Jaak Panksepp, a neuroscientist at the College of Veterinary Medicine at Washington State University, disagrees. Most famous for his studies demonstrating that tickled rats “laugh” in high-pitched chirps inaudible to the human ear, Panksepp researches underlying, unconditioned emotional systems. When it comes to fear, this means instinctual, native fears, not fears created in the laboratory by repeated foot-shocks. Using deep-brain stimulation on an animal’s amygdala, hypothalamus, and midbrain periaqueductal gray—the center of the fear system in humans—Panksepp is able to trigger these instinctive fears, and then watch how the animals react. He’s discovered that activating the fear response causes animals not only to go into typical fight or flight mode, but also to try to stop the experience—to turn off the terror in their brain. Humans exposed to deep-brain stimulation in these regions experience existential fear, describing their emotions (according to studies quoted in Panksepp’s 2012 book The Archeology of Mind) in terms like “I’m scared to death” and “an abrupt feeling of uncertainty just like entering into a long, dark tunnel.” Rats and mice, says Panksepp, likely experience something just as unpleasant.

Of course, fear is not the same thing as anxiety. While fear is a primary-process emotion, anxiety is more complex. “It’s something you’re reflecting upon, your confrontations in the world, who’s treating you poorly,” Panksepp says. “We cannot look at the thoughts of an animal—no one has a methodology for that.” However, Panksepp says, he suspects animals experience their own kind of “thoughtful worries.” “I personally believe they do because they’ve got plenty of upper-brain material in areas that we know control human thinking and worry about basic survival ideas.”

Some might argue that I am anthropomorphizing, but the result has been positive for everyone.

Other scientists agree, both with the difficulty of defining animal anxiety and with the possibility that it could exist. Lori Marino was a neuroscientist at Emory University and is now the executive director of the Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy. Anxiety among animals “is more debatable because it has a component that fear doesn’t have and the component is time,” she says. A sense of one’s self existing in time is fundamental to anxiety. You worry about your future self—where will I be tomorrow, in three weeks, in a month? You mull over past regrets.

For a long time, most scientists have believed humans are unique in having a concept of ongoing time. But recent studies of Western scrub-jays and Eurasian jays (two corvid, or crow, species) have shown the birds anticipate later feeding needs even when those needs are different from what they want in the present. A 2013 study suggested that chimpanzees and orangutans in zoos may have human-like autobiographical memories—that a single cue can activate a series of remembered events, just the way it does for humans.

It’s still a leap to assume that a more complex relationship with time implies a set of emotions around those remembered or planned for events—although one recent study found that pigs engage in “avoidance behavior,” balking and oinking, when anticipating a negative task in the future. But it does raise some intriguing possibilities.

“I think you can say that many animals have some sense of time,” Marino says. “It may not be exactly as sophisticated as that in humans, but I think they are able to anticipate something, they know that something is going to happen in the future, even if it is just a few minutes or a few hours or a few days. It’s just not possible to survive with just being fearful, without also feeling some anxiety about what might happen or anticipate it, even in the simplest sense.”

For me, labeling Lucas as anxious changed everything in how I thought of his behavior. I had seen him as an adversary: robbing my sleep, peeing on my kid’s rug, bullying me and my family and my other cat. Now he was a fellow sufferer. Some might argue that I am anthropomorphizing, but the result has been positive for everyone. As I became more sensitive to Lucas’s neuroses, I began to notice my role in them.

Animal anxiety, to say the least, is frequently caused by humans—from our destruction of their habitats to our hunger for their flesh to our imprisonment of them in zoos. But we often cause anxiety in the animals that have evolved to live beside us, that we love most intensely and view as our companions, by imposing our needs on them and ignoring theirs. Dogs and cats alike need lots of stimulation and exercise; we like to live in cities and work all day. Cats like to be stroked on the cheeks and chin; we hug and cuddle them like stuffed animals, even when they are obviously upset by it.

When I thought about Lucas as anxious, I also began to think about his needs more than I had before. I played with him more often and gave him more, smaller meals. He responded as well to the meals and play as he had to the antidepressants, which he had not been taking as much because he rejected the food I put them in. He stopped waking us up in the middle of the night and marking in my son’s room. Science may be only partway to understanding whether Lucas is anxious, in the Kierkegaardian sense, or just acting like he is. In the end, it became more useful to be generous about the definition of anxiety—to recognize a connection, and also my own responsibility, in whatever anxious might mean for Lucas.

Britt Peterson is a contributing editor at Washingtonian magazine and a writer on ideas and culture for Smithsonian, the Boston Globe, Slate, and Elle.com.