In 1932, the Soviet Union sent one of its best agents to China, a former schoolteacher and counter-espionage expert from Germany named Otto Braun. His mission was to serve as a military adviser to the Chinese Communists, who were engaged in a desperate battle for survival against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists.

The full story of Braun’s misadventures in China’s Communist revolution is packed with enough twists and turns for a Hollywood thriller. But in the domain of culinary history, one anecdote from Braun’s autobiography stands out. Braun recalls his first impressions of Mao Zedong, the man who would go on to become China’s paramount leader.

The shrewd peasant organizer had a mean, even “spiteful” streak. “For example, for a long time I could not accustom myself to the strongly spiced food, such as hot fried peppers, which is traditional to southern China, especially in Hunan, Mao’s birthplace.” The Soviet agent’s tender taste buds invited Mao’s mockery. “The food of the true revolutionary is the red pepper,” declared Mao. “And he who cannot endure red peppers is also unable to fight.’ ”

Taste of Sichuan

By Andrew Leonard

If there is a single dish that most exquisitely captures Sichuan’s love for the chili pepper, and perhaps its revolutionary fervor, it’s La Zi Ji—“Spicy chicken.”

The cooking process isn’t too complicated—morsels of fried chicken are stir-fried with an enormous amount of chili peppers—though the visual impact is intimidating.

But have no fear, the look is scarier than the bite. The flavor of the chili pepper is blunted by the numbing tingle induced by ground Sichuan peppers (a condiment unre- lated to either chili peppers or black peppers). The ensuing taste sensation is entirely unique to Sichuan cuisine.

My favorite recipe for this dish is the one below from Taylor Holliday, author of The Mala Project, a blog devoted to Sichuan food.

Try the recipe out, and share your results to the Nautilus Facebook page.

Photo: The Mala Project

Maoist revolution is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when your tongue is burning from a mouthful of Kung Pao chicken or Mapo Tofu at your favorite Chinese restaurant. But the unlikely connection underscores the remarkable history of the chili pepper.

For years culinary detectives have been on the chili pepper’s trail, trying to figure out how a New World import became so firmly rooted in Sichuan, a landlocked province on the southwestern frontier of China. “It’s an extraordinary puzzle,” says Paul Rozin, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist, who has studied the cultural evolution and psychological impact of foods, including the chili pepper.

Food historians have pointed to the province’s hot and humid climate, the principles of Chinese medicine, the constraints of geography, and the exigencies of economics. Most recently neuropsychologists have uncovered a link between the chili pepper and risk-taking. The research is provocative because the Sichuan people have long been notorious for their rebellious spirit; some of the momentous events in modern Chinese political history can be traced back to Sichuan’s hot temper.

As Wu Dan, the manager of a hotpot restaurant in Chengdu, Sichuan’s capital, told a reporter: “The Sichuanese are fiery. They fight fast and love fast and they like their food to be like them—hot.”

The chili pepper, genus capsicum, is indigenous to the tropics, where archaeological records indicate it has been cultivated and consumed perhaps as far back as 5000 B.C. Typically a perennial shrub bearing red or green fruit, it can be grown as an annual in regions where temperatures reach freezing in the winter. There are five domesticated species, but most of the chili peppers consumed in the world belong to just two, Capsicum annuum and Capsicum frutescens.

The active ingredient in chili peppers is a compound called capsaicin. When ingested, capsaicin triggers pain receptors whose normal evolutionary purpose is to alert the body to dangerous physical heat. The prevailing theory is the chili pepper’s burn is a trick to dissuade mammals from eating it, because the mammalian digestive process normally destroys chili pepper seeds, preventing further propagation. Birds—which do not destroy chili pepper seeds during digestion—have no analogous receptors. When a bird eats a chili pepper, it doesn’t feel a thing, excretes the seeds, and spreads the plant.

The word “chili” comes from the Nahuatl family of languages, spoken, most famously, by the Aztecs. (One early Spanish translation of the word was “el miembro viril”—tantalizing early evidence of the chili pepper’s inherent machismo.) Botanists believe the chili pepper originated in southwest Brazil or south central Bolivia, but by the 15th century, birds and humans had spread it throughout South and Central America.

Enter Christopher Columbus. On Jan. 1, 1493, the great explorer recorded in his diary his discovery, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, that “the pepper which the local Indians used as spice is more abundant and more valuable than either black or melegueta pepper [an African spice from the ginger family].”

In the 15th century, Spain and Portugal were obsessed with finding sea routes to the spice markets of Asia that would allow them to break the monopoly wielded by Arab traders over access to hot commodities like black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, and ginger. Although Columbus was utterly wrong in his belief that he had sailed to India, he still succeeded in locating precisely what he had been seeking.

What he found was a potent, popular spice—the natives, observed Columbus’ physician Deigo Chanca, included chili pepper with every meal. The plant Columbus encountered is believed to be Capsicum annuum or frutescens, which he described as “like rose bushes which make a fruit as long as cinnamon.”

Eating chili peppers is like riding a roller coaster. It delivers a rush of danger and pleasure.

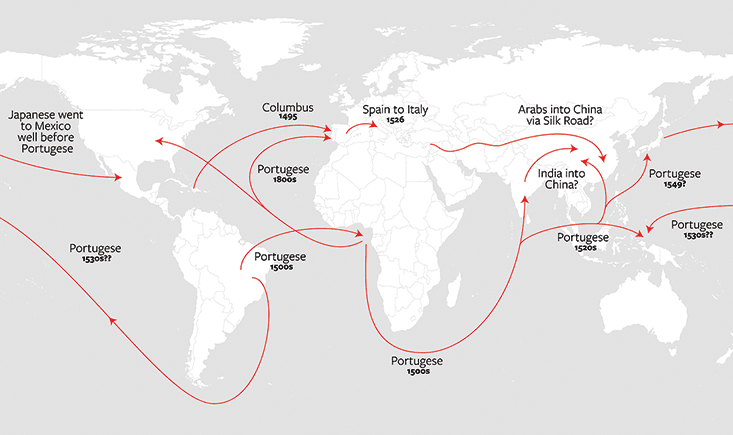

The chili pepper, like so many edible plants native to the New World, proved to be a wildly popular global sensation. Within a century of Columbus’ arrival in the New World, the chili pepper had made its way to places as far-flung as Hungary (paprika!), West Africa, India, China, and Korea.

The first mention of the chili pepper in the Chinese historical record appears in 1591, although historians have yet to arrive at a consensus as to exactly how it arrived in the Middle Kingdom. One school of thought believes the pepper came overland from India into western China via a northern route through Tibet or a southern route across Burma. But the first consistent references to chili peppers in local Chinese gazettes start in China’s eastern coastal regions and move gradually inland toward the West—reaching Hunan in 1684 and Sichuan in 1749—data points that support the argument that the chili pepper arrived by sea, possibly via Portuguese traders who had founded a colony near the southern Chinese coast on the island of Macao.

Historians and ethnogastronomes have been confounded by the fact that other parts of China with exposure to the chili pepper sampled it and shrugged. Notably, in the southeast, the Cantonese easily resisted its blandishments while maintaining allegiance to their own much more subtly flavored cuisine. But in Sichuan, the chili pepper stuck. Clearly some constellation of factors made the province different.

Due in large part to its dramatic geography, Sichuan has enjoyed a distinct historical identity in China dating back thousands of years. Separated from its neighbors by majestic mountain ranges and rivers, while at the same boasting a temperate climate and a fertile central plain so conducive to agriculture that the province was nicknamed the “Land of Plenty,” Sichuan has been a refuge when things were going wrong elsewhere in the empire.

One of the most dramatic events in Sichuan’s history came in the 17th century, as the Ming dynasty was collapsing and the Qing began to consolidate power. During the Ming-Qing transition, a devastating set of disasters—rebellions, banditry, famine—resulted in massive depopulation. The best guess is that as much as 75 percent of Sichuan’s population died or disappeared during this period.

Over the next century, one of the greatest instances of mass internal migration in the history of China substantially repopulated the province. The great majority of the new immigrants came from the two provinces directly to the east, Hunan and Hubei.

The historian Robert Entenmann wrote his doctoral thesis at Harvard on the great migration. According to his calculations, there were only around 1 million residents left in Sichuan by 1680, but between 1667-1707, 1.7 million immigrants arrived. So at about exactly the same time that the chili pepper had made its way as far inland as Hunan, the Hunanese were moving en masse to Sichuan, driven by overpopulation in their home province and sheer economic necessity.

Capsicum annuum is easy to grow in both tropical and temperate climates and maintains its potency when dried, making it ideal for long-term storage and transportation. At a time of great destruction, chili peppers were a relatively cheap source of flavor compared to salt and black pepper. As a Sichuanese folk saying goes: “Spicy peppers are the meat of poor guys.” Chili peppers also contain ample vitamin A and significant amounts of vitamins B and C. Flavorful, nutritious, cheap, and easy to grow; from a purely pragmatic standpoint, the chili pepper’s global adoption is easy to appreciate.

Another, more provocative explanation for chili pepper popularity holds that its geographical distribution can be explained by its purported anti-microbial properties. In a 1998 paper published in the Quarterly Review of Biology, Cornell’s Paul Sherman and Jennifer Billing found a correlation between the mean temperature of a country (or region) and the number of spices called for in recipes representing the “traditional” cuisine of that region. The equation was simple: The hotter the temperature, the more spices consumed. Their theory: Spices performed an anti-microbial function especially useful in tropical or subtropical regions where meat was likely to go bad quickly.

Over the past decade, researchers have found evidence of anti-bacterial properties in chili peppers, and broadly speaking, chili pepper consumption is more popular in tropical regions than elsewhere. The Sherman-Billing thesis also jibes with the traditional Chinese explanation of why Sichuan and Hunan love spice.

In her memoir Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper, Fuchsia Dunlop, an author of Chinese cookbooks, writes that the region’s passion for spice is explained by the intersection between climate and traditional Chinese medicine: “In terms of Chinese medicine, the body is an energetic system, in which damp and dry, cold and hot, yin and yang, must be balanced.”

Sichuan is notoriously humid—damp in the winter and hot in the summer. To counteract the soggy weather, the Sichuanese have historically spiked their diet with warming foods like garlic, ginger, and Sichuan pepper (a spice unrelated to the hot pepper that creates a numbing sensation on the tongue). When the chili pepper arrived, the Sichuanese plugged it seamlessly into their preexisting palate.

To appreciate how deeply the hot pepper has become embedded in southwestern Chinese culture, says Gerald Zhang-Schmidt, an Austrian cultural anthropologist who lived for three years in Hunan, look at the vigorous rhetorical competition between the Hunanese and the Sichuanese on the question of which province is less afraid of the hot pepper. Both provinces, the core of China’s “chili belt,” exalt the stereotype of the “spicy girl” (la mei zi) who is “at least as irascible as the chili is hot,” Zhang-Schmidt says. In a video of the pop song “La Mei zi” by Hunanese singer Song Zuying, scores of young, red-clad Chinese women frolic amid a harvest of tons of chili peppers, as Song Zuying sings:

As children, spiciness is not the spicy girls’ fear

As adults, spicy girls don’t fear the heat

Getting married, spicy girls fear that things might not be spicy enough.

From spice girls to revolution may not, after all, be that big a step.

In the 1970s, Rozin, of the University of Pennsylvania, studied the chili pepper-eating habits of Mexicans in a small village in Oaxaca. Today he believes the fundamental reason that people all over the world eat the hot pepper is simple: for the flavor and the burn. But they’re not born that way.

Unlike most foods humans are accustomed to eating, the chili pepper causes actual pain when ingested. That pain, scientists believe, is an artifact of evolution. When capsaicin comes in contact with nerve endings it trips a pain receptor whose normal function is to detect the kind of heat that is legitimately burning hot. The receptor, known as TRPV1, is designed to keep us from doing dumb things like picking up a burning branch with our bare hands, or biting into something so hot it would physically damage our mouths.

Based on his fieldwork in Oaxaca, Rozin determined that the act of eating chili peppers is an acquired taste in Mexico. Children do not come out of the womb craving a scorching hot cuisine. They’re trained, by their families, to handle the chili’s burn with small doses that gradually increase.

Little is known about the genetics of capsaicin sensitivity. Some variation may be linked to the same physical characteristics that make a minority of the population “supertasters,” those especially sensitive to bitter tastes. However, initial adverse reactions can be overcome by regular consumption. If you grow up in a culture where everybody eats chili peppers, you will likely become accustomed to eating chili peppers yourself, whether or not you are inherently more sensitive to capsaicin—or even more rebellious and thrill-seeking than your peers.

Nevertheless, Rozin saw that some people, even in Mexico, ate more chili pepper than others. And outside of traditional chili pepper-eating cultures, it is common to see people learn to love spicy food on their own. To explain this phenomenon Rozin came up with a theory he called “benign masochism.” A certain type of person, he theorized, was lured to the burn—the same kind of person, he suggested, who might be drawn to other “sensation-seeking” activities.

Eating chili pepper is like riding a roller coaster, he notes. “In both cases, the body senses danger and behavior normally follows which would terminate the stimulus. In both cases, initial discomfort becomes pleasure after a number of exposures.”

Linguistically and anecdotally, the association of “spice” with “excitement” rings true, but proof of Rozin’s theory did not arrive until decades after he formulated his original thesis. The missing link appeared in 2013, when two Penn State researchers, John Hayes and Nadia Byrnes, published “Personality Factors Predict Spicy Food Liking and Intake” in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

Hayes is an associate professor of food science at Penn State who received an NIH grant in 2011 to investigate the genetics of the TRPV1 receptor. Nadia Byrnes was one of his graduate students. In experiments conducted on 97 test subjects, Byrnes found a significant correlation between people who scored high on a “sensation seeking” scale and people who liked the burn. (Examples of questions that determined “sensation seeking” included “I would have enjoyed being one of the first explorers of an unknown land” and “I like a movie where there are a lot of explosions and car chases.”)

Byrnes, now a post-doc at the University of California, Davis, says her data shows that there are links between sensation-seeking and liking spicy food that align with Rozin’s theories “to an extent.” The data also suggest some provocative gender-based differences related to spice attraction. In comparison to women, Byrnes says, men may be more motivated to eat hotter food because of the “extrinsic rewards” provided by society: the “cultural expectation that being male includes machismo and strength and daring—all these kinds of stereotypically male characteristics.”

So does this mean Mao was right? That there is a link between revolutionary fervor and the chili pepper?

Both the Sichuan and Hunan provinces exalt the “spicy girl,” who is at least as irascible as the chili is hot.

Hongjie Wang, an associate professor of history at Armstrong State University in Georgia, specializes in Sichuan culture. In his essay, “Hot Peppers, Sichuan Cuisine and the Revolutions in Modern China,” he marshals some interesting data points supporting what one contemporary Chinese cultural observer called Sichuan’s inherent “potential for rebellion, so beautiful and marvelous.” In 1911, according to Wang, a protest against “imperialist” control of newly constructed railroads in Sichuan triggered national unrest that ultimately led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty, which means one can make the case that Sichuanese hot tempers set in motion the entire process of China’s modern political development.

In his essay, Wang emphasizes the insurgent fire of the Sichuan people. During the Sino-Japanese War between 1937-1945, he tells us, Sichuan provided nearly 3.5 million soldiers for the Chinese army, accounting for nearly a quarter of the total drafted forces during the wartime period. The Sichuan city of Chongqing served as Chiang Kai-shek’s war-time capital. Perhaps most compelling, he writes, of the 1,052 generals and marshals who served in the early ranks of the People’s Liberation Army, a whopping 82 percent hailed from China’s four spiciest provinces.

In Sichuan, Wang writes, “eating spicy food has come to be regarded as an indication of such personal characteristics as courage, valor, and endurance, all essential for a potential revolutionary.”

The puzzle starts to take shape. Personality: risk-taking immigrants on the move. Economics: a cheap and easy-to-grow option for adding flavor to a constrained diet. Weather and culture: a hot and humid climate, and yin and yang medical philosophy. Taken together, we see the formation of a culture, the beginning of an identity.

The final stroke cementing this modern act of identity-formation may not have arrived until the Sino-Japanese War, when the elite classes of China, fleeing to Sichuan from both the Communists and Japanese, found themselves in precisely the same kind of dire economic straits as those refugees who had immigrated to Sichuan centuries earlier. Then they too began to turn to the cheap, spicy, peasant fare that the lower classes had inadvertently nurtured into one of China’s great cuisines.

“The new wave of migration to Sichuan before and during the Anti-Japanese War in the 1930s finally witnessed the flourishing of Sichuan cuisine in today’s version,” says Wang.

Sometime late in the 19th century, a pock-marked woman known to history as “old lady” Chen started serving her signature dish, a blazing-hot stir-fried mixture of tofu and ground pork, in a small shop near the north gate of Chengdu.

Recipes for Mapo doufu vary, but a typical version includes fresh tofu stir-fried in a mixture of minced garlic and ginger, chili pepper paste, scallions, tree ears, water chestnuts, ground pork or beef, soy sauce, rice wine, rice vinegar, and Sichuan pepper. It’s impossible to single any one sensation out as more or less definitive than the other. It is the combination, the interaction of flavors, that tells the full tale.

To this day, there is a restaurant in Chengdu that purports to be the direct descendant of Chen’s original stall. And no wonder. The enduring popularity of the dish is not just about the interactive flavors. Mapo doufu offers an ideal metaphor for a society that thinks of itself as rebellious and revolutionary, that prides itself on its spiciness in every sense of the word.

The bite and the burn of the red chili pepper is a reminder of how the peasants of southwestern China, at the mercy of historical and economic forces, crafted culinary masterpieces from the basic instinct for survival. Out of poverty and war and the currents of globalization they fashioned fire for their palates, and ours.

Andrew Leonard is a writer living in Berkeley, California, working on a book about Sichuan food, globalization, and the Tao.