I teach one of the world’s most popular MOOCs (massive online open courses), “Learning How to Learn,” with neuroscientist Terrence J. Sejnowski, the Francis Crick Professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. The course draws on neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and education to explain how our brains absorb and process information, so we can all be better students. Since it launched on the website Coursera in August of 2014, nearly 1 million students from over 200 countries have enrolled in our class. We’ve had cardiologists, engineers, lawyers, linguists, 12-year-olds, and war refugees in Sudan take the course. We get emails like this one that recently arrived: “I’ll keep it short. I’ve recently completed your MOOC and it has already changed my life in ways you cannot imagine. I just turned 29, am in the middle of a career change to computer science, and I’ve never been more excited to learn.”

It’s a wonderful feeling to receive notes like this, as teachers around the world know. As gratifying as the note is personally, it also speaks for the impact of MOOCs. We all know about the importance of an education system, and how much society could gain if education, particularly for the disadvantaged, were improved. Online courses allow us to scale up those opportunities—a better education at lower cost. Already the numbers are impressive. More than 500 colleges and universities and 200 organizations and institutions offer MOOCs, with a total of 30 million users.

At the same time that “Learning How to Learn” has been one of the most satisfying experiences of my 20 years as a teacher—I am currently a professor of engineering at Oakland University in Michigan—I confess to feeling a little defensive. The success and tremendous educational potential for MOOCs has been dinged by some high-profile articles in the past couple of years. In an article called “Trapped in the Virtual Classroom” in the New York Review of Books, David Bromwich, the Sterling Professor of English at Yale University, claimed that the “MOOC movement cooperates with the tendency of mechanization” and “discourages more complex thinking about the content and aims of education.” Some research papers have reported the dropout rate in MOOCs is above 90 percent. And Robert Zemsky, Chair of the Learning Alliance for Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, has written that MOOCs, facing diminishing prospects, “were neither pedagogically nor technically interesting.”

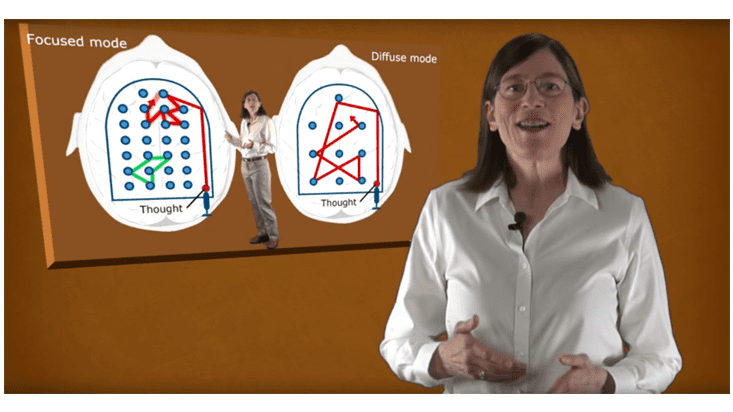

Human brains have evolved with a flitting, fleeting ability to maintain focus on any one thing.

I would venture to say most MOOC deniers have little experience with creating and teaching online courses. The reality is MOOCs can be artistically and technically fascinating and can have terrific pedagogical advantages. This is particularly true in the fraught area of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math), where difficult explanations often cry out for a student to replay a portion of a lecture, or simply to take a pause while comprehension works its way to consciousness. As for those dropout rates, Keith Devlin, a mathematician at Stanford University, has pointed out that some widely cited papers on MOOC attrition have depended on traditional metrics of higher education that are “entirely misleading.” People sign up for MOOCs for different reasons than they do for traditional college classes. “A great many never intend to complete the course,” Devlin writes. They “come looking for an education. Pure and simple.”

With the best MOOCs, students are getting an education that does indeed encourage complex thinking about the goals of education. Online courses can hold students’ attentions, at times better than teachers can. Creating “Learning How to Learn” provided an opportunity to do a “meta” on teaching and learning. Terry and I could use the online medium to help overcome some of challenges that students experience when facing traditional methods of teaching, and give them insight into the learning process itself.

Chilean recluse spiders are believed to be among the most dangerous recluse spiders. One bite can kill you. Those suckers are big—up to an inch and a half across. They’re also very fast. Imagine you spot a Chilean recluse spider 20 feet in front of you on the floor. Look again—suddenly, it’s two feet in front of you. That gets your attention, doesn’t it?

We’re beginning to tease out the neurocircuitry behind why motion—especially looming motion like that of a spider—attracts attention. When looming objects are detected, neurons send a cascade of information to the brain’s amygdala, a processing center of emotions and motivation. Looming is a big deal, phylogenetically speaking—creatures as different as insects, reptiles, birds, and people respond to looming motion.1

Human brains have evolved with a flitting, fleeting ability to maintain focus on any one thing. Those who kept too fixed a gaze on the wildebeest they were stalking could end up being killed by the lions stalking them. So it shouldn’t be a surprise to learn that humans may not have been meant to sit boxed up for prolonged periods, focused on a teacher in a classroom. No matter how much we might like or be interested in the material, a lecture is out of tune with how our brains work.

This is a problem for teaching. It sounds heretical to even ask whether teachers help us learn. Our intuition tells us they should. And in fact they do help us learn—the best teachers seem to get inside our heads to intuit just what we need to get that ah ha! of initial understanding. They can charm, bedevil, and inspire us to learn well, even when the mountaintop of mastery seems insurmountably high. Clear explanations, inspiration, humor, personal focus on individual pressure points of conceptual misunderstanding—they all help us want to keep moving forward in the sometimes difficult task of learning.

But counterintuitive research has shown that teachers don’t seem to help us learn very well. A 1985 paper, “The initial knowledge state of college physics students,” by physics professors Ibrahim Abou Halloun and David Hestenes, revealed that when we put physics students in front of a traditional “talk-and-chalk” instructor, those students claw their understanding of physics forward by only a tiny amount—even when the teacher is an award-winner.2

One of the tricks used by many of the past greats in science has been to imagine themselves transported into what they’re trying understand.

The Halloun and Hestenes paper produced an upheaval in science education. How could it be that traditional methods did such a poor job of educating? As researchers grappled with the implications, they began to test out new and better methods for teaching. Seminal research by physicist Richard Hake and others revealed that interactive engagement in a classroom, including big classrooms with over 100 students, resulted in a marked improvement of knowledge gained in a semester, compared to more traditional “sage on the stage” approaches.3 Maintaining students’ attention can be improved, it seems, by allowing them to talk and work interactively with one another.

Many college classrooms have shifted to this approach. A meta-analysis by Scott Freeman and his colleagues in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences revealed that “active” learning produces such an improvement in science, engineering, and math classrooms that it is almost pedagogical malpractice not to use it.4 But learning can’t all be interaction. Sometimes the more the interaction, the slower the progress. Usually, proponents of active learning (I’m one of them; I coauthored a 2004 paper on the subject) suggest that a good approach to teaching provides a balance of explanation time by the instructor coupled with “active” time, where students are able to grapple with the material themselves, often while interacting with teammates.5

The resolution to the paradox about the value of teachers lies, it seems, in the context of the researcher’s studies. Private tutoring can naturally hold a student’s attention by not only giving clear explanations, but by switching things up, asking questions, and taking short breaks as needed. In the traditional talk-and-chalk larger classrooms that Halloun and Hestenes were investigating, even the best teachers couldn’t help but become boring as a lengthy college class among a herd of other students dragged on.

These findings point toward the flitting nature of our brains—driven much more than we might like to admit by elusive, unconscious factors. Our inability to maintain focus for lengthy periods of time, coupled with our need to try things out for ourselves and talk things out with others, reduces our ability to make the best use of teachers who teach in traditional sage-on-the-stage form.

With the advent of the Internet, an even newer approach to teaching has been the “flipped” classroom. In this approach, professors are recorded on video so they can be viewed at home, helping to synthesize and bring key ideas to life. Class time is then taken up with answering questions and with collaborative interactions: solving problems, discussing issues and concepts in teams, and working out the misunderstandings that have arisen during the preliminary solitary study. These types of personal interactions are where the teacher, and other students, are both invaluable.

The development of the flipped class has led to MOOCs as the next important frontier in education.

Perhaps my biggest asset to creating “Learning How to Learn” was that I had been a terrible student. I flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. Remedial math didn’t even hit my playbook until age 26, after I’d gotten out of the military. (Poor job prospects can be a great motivator for career change.) I couldn’t learn well by listening to lectures—in class, virtually everything but the professor was a shiny object of glorious distraction for me. The only way I could ultimately be successful was to become a classroom stenographer—later studying the notes at my own pace and in my own way.

As I started to learn math as an adult, I was often terribly frustrated by the material—sometimes I felt that textbooks and professors ganged up to present matters in the most arcane way possible. Whenever some professor with a near lifetime experience with Fourier and Laplace transforms would say something like, “Of course, it’s intuitively obvious that …” I’d get a shiver, because I knew it wouldn’t be intuitively obvious to me. I’m not a quick study—it would often take me a long time to see that what I was looking at was actually very simple.

Terry and I created “Learning How to Learn” to get students to grasp that simplicity themselves. We wanted to incorporate some of the advantages of face-to-face tutoring with recent lessons from video game makers and TV. From the fast pace of Grand Theft Auto to money flying in a dryer in Breaking Bad, motion is an important aspect of reaching deep into viewers’ subconscious to get a lock on their attention.

In “Learning How to Learn,” we make assiduous use of motion. Using green screen, I can suddenly pop from one side of the screen to another. Or I can loom from full standing to a close up of my face. Or, as I laugh on the side of the screen, I can speed up the onscreen picture-in-picture video of my daughter ineptly backing the family car off the driveway and onto the lawn—a living example of what can happen when procedural fluency hasn’t been acquired. It’s all video trickery, of course, but it works to keep students’ attentions.

In fact, one of the tricks used by many of the past greats in science has been to imagine themselves transported into what they’re trying understand. Einstein famously imagined himself chasing a beam of light to help him formulate theories of relativity. Nobel Prize winner Barbara McClintock imagined herself in the realm of the “jumping genes” she became famous for discovering. We can help our students to develop the same sort of intuition as these Nobel Prize winners by bringing objects to life in video in a way that’s virtually impossible to do in a classroom. We can walk into the mitochondria of a cell, or the ionic interaction that sparks an aurora, or the spiraling epiphany of Euler’s equation.

Online videos allow students to do what their brains are naturally geared for—focusing, replaying the toughest parts of what they’re trying to learn, then taking a break.

A technology often used in current “in person” classroom instruction is to have a PowerPoint slide on the screen while the instructor stands to the side. Mimicking this approach in video format, we often see a small talking head in the corner of the screen (which is basically, because of its limited range of motion, like a still image), while the main image—whether it’s a piccolo or a Picasso—is enlarged and discussed on another part of the screen.

But this “two image” approach actually increases a learner’s cognitive load. With two separate images on the screen, you’ve got to process two different things at once. However, green-screen technology can allow a professor to appear to walk around a digitally upsized Greek vase that’s the same size as she. In a biology video, the professor can point to life-sized structures of the cell. In engineering, she can point to the counter flow aspects of a heat exchanger. This cinematic joining of professor and object-under-discussion into one image reduces cognitive load and focuses students’ attention on important details—even when, in real life, those details are small. All this has a big effect in making it easier for students to grasp key ideas.

Metaphors and analogies are just as important to learning as reducing the cognitive load. A theory called “neural reuse” posits that we seem to often use the same neural circuits to understand a metaphor or analogy as we do to understand the underlying process itself.6 When we use water flow as an analogy for electron flow, or the idea of a stalker who creeps ever closer to help us understand the concept of limits in calculus, we’re calling into play the same neural circuits that underpin our ability to understand those abstract concepts. Science, engineering, and math professors can be a bit snooty about dumbing down their material through sometimes silly analogies. These types of pedagogical tools are extraordinarily valuable—they serve as intellectual on-ramps to get students on board with complex ideas more quickly by using pre-existing neural circuitry.

Good online courses make students feel professors are speaking directly to them. A teacher’s direct focus on the camera translates as personal attention in the videos. Students develop a sense of familiarity; we are often seen as friendly private tutors. It makes us more approachable and “listen-to-able.” It’s not that we’re replacing teachers in a classroom. It’s that we serve as additional personalized resources, despite the fact that we’re explaining at massive scales. And I should mention that every single video lecture I give in our MOOC is the best lecture on that topic I’ve ever given in my life.

Online classes make enhanced quizzing available. Testing, as it turns out, is one of the best ways we can learn.7 Tests at key points in videos, and dozens of carefully created alternative quiz questions at the end of each module, can do a lot to improve students’ understanding of the materials. Educators sometimes point to research from physics showing that students don’t really learn from careful explanations—they learn from making mistakes. But physics, unlike most subjects, is rife with pre-existing misconceptions that induce students to skip past explanations because they think they already understand—a stuck-in-a-rut mindset known as “Einstellung.”8 Mistakes in the frequent low-stakes quiz questions available online can force students in physics—or any other subject—to revisit the explanation.

So online videos allow students to do what their brains are naturally geared for—first focusing, then replaying the toughest parts of what they’re trying to learn, then taking a little break. They can quiz themselves, or I can quiz them. They can stop the video and stare into the distance, thinking away until all of a sudden, it clicks. They can touch base on the discussion forums with a friend in Zimbabwe or Chile. Much of this is impossible to do in a conventional 2-hour class period. (Have you ever tried to follow 10 fully worked out examples of Bayes Theorem in a 2-hour class period?)

Not all MOOCs are fabulous. But with their increasing diversity and quality, what MOOCs offer students—those enrolled in colleges and those not—is choice. Students can sample a wealth of subjects and classes, and if they are not sparked, move on. And MOOCs alone aren’t the answer to improved education. That will come from a variety of sources: MOOCs, resources developed by textbook companies, and teachers themselves. Online assets will not serve as a replacement for in-person instructors—rather, they’ll serve as assets, providing high-quality personalized tutoring and great testing materials with rapid grading.

Terry and I made “Learning How to Learn” for less than $5,000, and largely in my basement. I had no previous film editing experience—in fact, I could barely click a camera shutter. Much of the moving imagery for the course was created using simple PowerPoint slides. So I would issue a challenge to MOOC critics. Make your own online course. Film the most interesting, most insightful lecture you’ve ever given in your life. If you don’t think your lecture is good enough, reshoot it until you’re happy. Make your video available for millions of students around the world, not just the privileged few in your classes. Come up with questions for a quiz on the mistakes you most commonly see in your classes. You will learn more than you know about the outreach and capabilities of MOOCs. More importantly, you will exemplify a wonderful openness for learning to students everywhere.

Barbara Oakley is a professor of engineering at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, and the author of, most recently, A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). She is co-creator, with Terrence J. Sejnowski, of the online course, “Learning How to Learn.”

References

1. Skarratt, P.A., Gellatly, A.R., Cole, G.G., Piling, M., & Hulleman, J. Looming motion primes the visuomotor system. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 40, 566-579 (2014).

2. Halloun, I.A. & Hestenese, D. The initial knowledge state of college physics students. American Journal of Physics 53, 1043 (1985).

3. Hake, R.R. Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics 66, 64 (1998).

4. Freeman, S., et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 8410-8415 (2014).

5. Oakley, B., Brent, R., Felder, R.M., & Elhajj, I. Turning student groups into effective teams. Journal of Student Centered Learning 2, 9-34 (2004).

6. Anderson, M.L. Precis of after phrenology: Neural reuse and the interactive brain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 16, 1-22 (2015).

7. Keresztes, A., Kaiser, D., Kovacs, G., & Racsmany, M. Testing promotes long-term learning via stabilizing activation patterns in a large network of brain areas. Cerebral Cortex 24, 3025-3035 (2014).

8. Bilalic, M., McLeod, P., & Gobet, F. Why good thoughts block better ones: The mechanism of the pernicious Einstellung (set) effect. Cognition 108, 652-661 (2008).