In the span of nearly 5 years, Uber has gone from a limited launch in San Francisco to offering rides in more than 300 cities worldwide. In China alone, despite existing in a legal gray zone, the company claims it arranges 1 million rides per day. That means 35 Chinese people hop into an Uber there every time you blink.

But are there limits to how much Uber can scale? There might be: Us.

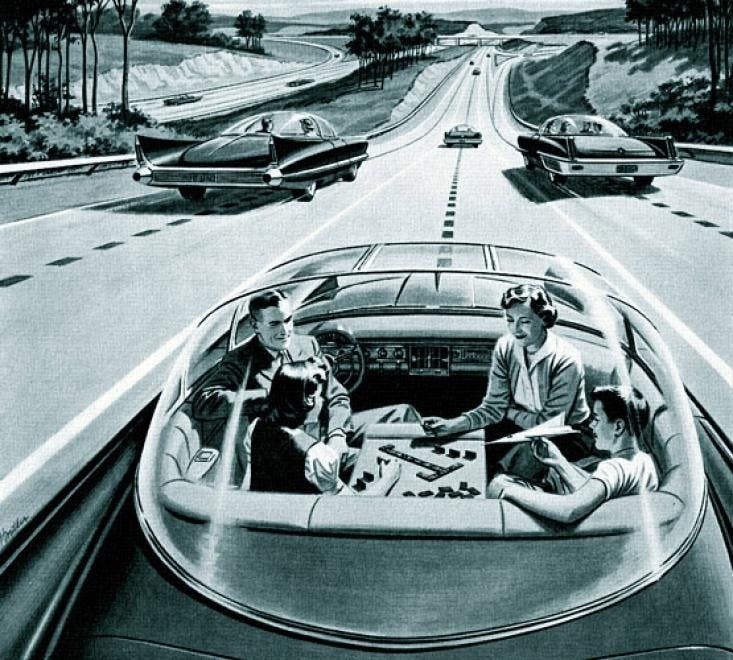

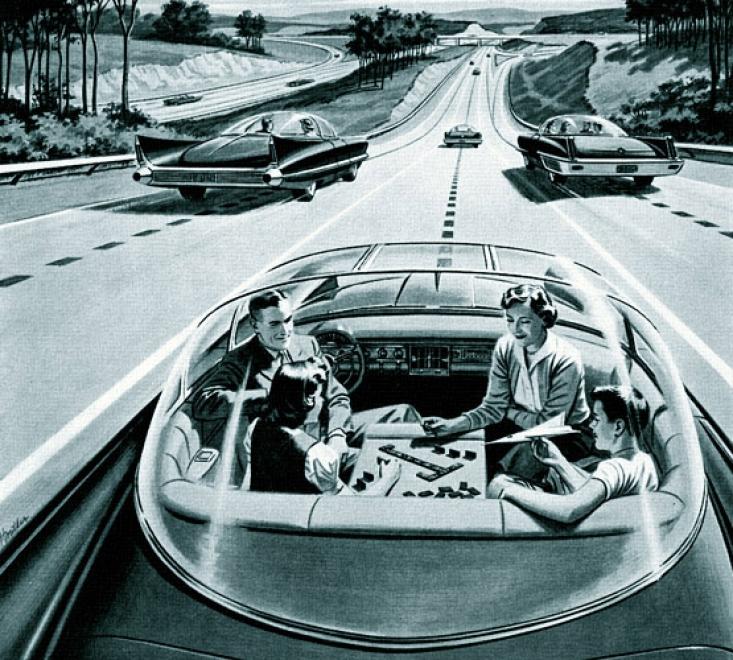

“The natural end point has to rely on autonomous driving technology”—not humans, says Emilio Frazzoli, director of the Transportation@MIT Initiative. He thinks robots could be taking the wheel in the next 15 years, certainly within the next 30. The reasons, he says, are economical and cultural.

First, as much as 50 percent of an Uber ride’s cost goes toward paying the human behind the wheel, Frazzoli says, and that’s money that could be going into Uber’s pocket. Replacing human operators has already begun in Singapore, a city that relies heavily on public transit. It’s not widely advertised, Frazzoli says, but the subway trains there “are completely automated. They are just horizontal elevators.”

Felix Oberholzer-Gee, a professor at Harvard Business School, agrees. Uber, he says, is a perfect example of a business that benefits from network effects, where the value of its service increases with more use. But, unlike other companies that benefit from strong network effects, such as Facebook, Uber has to deal with bringing two different types of users—and networks—together: drivers and riders. The network effects of getting rid of human drivers, he says, “will make the platform even stronger.”

Plus, for reasons from supply to quality control, Oberholzer-Gee says getting drivers will likely always be more of a headache than finding more riders. With autonomous vehicles, he says, “You could have a guaranteed supply of one of the sides, and particularly of the side that is harder to manage.” Uber might already be learning how cheap they can pay their drivers during a transition to vehicle autonomy. “They want to test the bottom line,” a Chinese Uber driver told MIT Technology Review, “just to see how much lower they can go before you quit.”

Second, Uber’s urban saturation is making a lot of people rethink the idea of owning a car, Frazzoli says, “versus just taking an Uber.” That’s no accident: As Uber’s general manager in Vietman recently told Reuters, “Our goal is to replace private car ownership.” Carnegie Mellon computer scientist David Andersen is on board. “What an unfortunate waste of resources,” he wrote in his blog, referring to the cost of using his car, which he recently sold. “Taking public transit, uber, or cabs…wouldn’t have been free, but it would have been better for my wallet.”

Uber is a perfect example of a business that benefits from network effects, where the value of its service increases with more use.

Stowe Boyd, lead researcher at GigaOM Research, which specializes in emerging technology, thinks more and more people will follow Andersen’s lead once self-driving cars arrive. They will “radically decrease car ownership,” he told Pew Research Center. “Perhaps 70% of cars in urban areas would go away.” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick has already acknowledged this potential future. “This is the way of the world,” he once said, “and the world isn’t always great.” Apparently to bring it about, Uber hired away 50 researchers from Carnegie Mellon’s National Robotics Engineering Center, a third of the department’s staff, for a developmental project on self-driving cars. (A month later, in February, the company and school announced a “strategic partnership” that makes the hiring seem a little less like brain poaching.)

If the custom of car-ownership dramatically dissolves, then Uber’s mass of potential drivers will, too. Driver scarcity will serve as another forcing function on Uber’s business model, further compelling it to evolve toward autonomous cars.

Oberholzer-Gee, however, doesn’t think it would be in Uber’s best interest to manufacture its own fleet of self-driving cars. That would change its strategy from, he says, “a very asset-light business model that Wall Street and the investors love, to sitting on billions and billions of dollars of invested assets.” That is a particularly difficult proposition given the dramatic fluctuations that happen to ride demand and availability. A large fleet of vehicles is needed at peak times, but a fleet that sits idle during off hours is just an added expense. “Regular drivers and autonomous vehicles have similar properties that I think make the Uber model difficult to scale,” says Oberholzer-Gee.

Say Uber (which declined to comment for this story) does decide to ditch its human drivers and opts not to operate its own fleet of self-driving cars: Who would do it for them? Oberholzer-Gee suggests that a large car manufacturer, such as Toyota, could be ideal. But then again, maybe it will be autonomous car owners themselves that will make up the next generation of Uber “drivers.”

Tesla recently unveiled its autopilot feature for the Model S, its luxury sedan. In the near future, it may be worth it for current or prospective Uber drivers, or anyone, to shell out $35,000 for Tesla’s economy car, the Model 3 sedan, due in 2017. Then, once the Model 3 becomes fully autonomous, it could just earn their owners a day’s wage now and then.

Jon Kelvey is a freelance writer and a reporter for The Carroll County Times.