The Grand Prismatic Lake in Yellowstone National Park is rightfully famous for the beautiful colors produced by its unique chemistry. But there are also other places where chemistry and geology combine to create vivid natural colors, in hot springs, rock formations, and even normally monochrome glaciers.

Chinoike Jigoku, or Bloody Hell Pond, is one of a series of linked hot springs in the city of Beppu, in Japan’s Oita Prefecture, known as the Eight Hells. With temperatures in some of the springs reaching as high as 302 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius), the waters are too hot for a relaxing dip, but that doesn’t dissuade tourists who come to marvel at the superheated springs. Bloody Hell Pond gets its distinctive crimson hue and horror-film name from the red clay at its base, which is laden with magnesium oxide and iron oxide.

Bloody Hell Pond isn’t the only one of the Eight Hells that is strikingly colored. Visitors can snack on hard-boiled eggs cooked over the steaming waters of Umi Jigoku, which gets its startling blue coloration from iron sulfate.

In the Triassic Period, more than 200 million years ago, huge rivers flowed across what is now Arizona, carrying sand and silt along with them. Compressed over the course over eons, those particles now compose the colorful Chinle Formation in the Painted Desert Petrified Forest National Park. At the Teepees, the variety of hues present in these distinct deposits is on full display. The result is a series of sandstone and mudstone hills that look like cakes with layers of blue, purple, green, grey, white, and red.

Located in western Egypt, the White Desert is a remote wonderland where white chalk monoliths, carved into exotic shapes by wind erosion, tower above forbidding sand dunes. Formed from the shells of ancient marine animals known as coccolithophores, these startling formations compose a monument to the history of one of the driest places on Earth, back when it was actually an ancient seabed.

The Yellow Mounds in South Dakota’s Badlands National Park are an example of a paleosol, an ancient layer of soil that was buried and became fossilized. The paleosol was once a dark layer of mud at the bottom of a seashale (pdf), but after the hills were uplifted and then exposed to the elements for years, the soil turned into an infertile, Crayola-yellow layer that forms the base of these stubby hills.

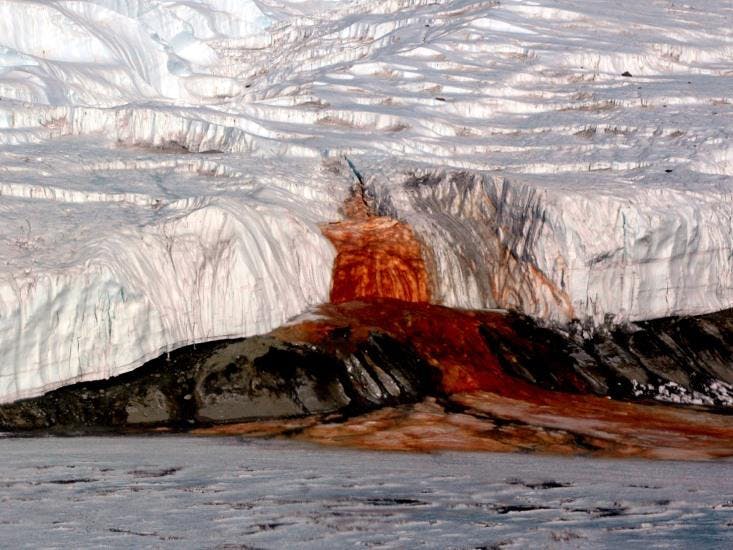

Blood Falls looks like a gusher of organic matter flowing freely from a wound in the side of Antarctica’s Taylor Glacier. But (with apologies to Shakespeare) if you prick a glacier, it does not bleed. The actual source of the brick-red liquid that flows from the glacier is an iron-rich saltwater lake covered over by the glacier more than a million years ago. The lake water flows out through a cleft inside the glacier and out through its edge, producing a steady flow of red, rusty water down into nearby Lake Bonney.

Ian Chant is a science and technology journalist and an editor at IEEE Spectrum.