Skin may seem like a superficial human attribute, but it’s the first thing we notice about anyone we meet. Nina Jablonski came to this realization many years ago when she was teaching a human anatomy class to young medical students in Hong Kong. When faced with dissecting a dead body, they flinched at the thought of cutting into or even touching it. But they lost their inhibitions once they opened up the cadaver. Without skin, the corpse no longer looked human.

Jablonski got hooked on all things related to human skin. As a primatologist and paleobiologist, she wanted to understand why humans—alone among the primates—evolved to become the naked ape, and why skin comes in so many different hues and shades around the world. Once she started investigating the science of skin color, Jablonski was pulled into the sordid history of racism, and she saw how even great thinkers like Kant and Thomas Jefferson believed people with dark skin were innately inferior to light-skinned people like themselves.

As a young girl, Jablonski learned that one of her great-great-grandfathers was a “Moor” from northern Africa, which embarrassed her family but helped explain why, she has written, she had one of the darkest pigmentations of any kid at her school in upstate New York. Later, when she launched her academic career, she discovered that color anxiety permeated her own field of anthropology. Today, she’s an anthropologist at Penn State University with a long string of published articles and two books, Skin: A Natural History and Living Color: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Color.

I talked with Jablonski about how the emerging science of skin color could inform today’s public discussion about race. She grew animated when commenting on scholars who believe there are biological differences between races, even on the loaded issue of intelligence. In our conversation, Jablonski ranged over various issues—from human evolution to the history of slavery—as she described her fascination with skin.

Do you think about your own skin?

I think about it every day. Everyone, including me, looks in the mirror and says, “Hmmm, getting a bit older.” I see it as my autobiography. My skin has seen everything that I have, all of the weather, the sorrow, the happiness, the toil. I love the changes that I see in my skin, and I see it as part of my human story.

What about skin color? Why does this interest you as a scientist?

It is one of the most fundamental ways in which people vary in their appearance. People have also made a big deal about skin color. It’s caused humanity a lot of difficulties because people have associated color with the value of human character and moral values.

Do we know when dark skin first evolved in our ancient ancestors in Africa?

We can make a very good estimate from the fossil record, as well as from studies done by human geneticists. Humans probably evolved naked skin around a million and a half years ago, and at the same time they mostly lost their coat of fur. Today we have a few tufts of hair remaining on various parts of our bodies, but compared to our primate relatives, we are relatively hairless. Basically we’ve turned on the pigment-producing capabilities of our skin cells and allowed this dark pigment called melanin to serve as a natural sunscreen in the place of the hair we lost.

Why did we lose our fur?

We think it occurred because of the need to keep ourselves cool when we were moving around very vigorously in a hot environment. Around 2 million years ago, we see the evolution of the first members of the genus Homo. These ancestors were tall, strapping, strong walkers, vigorous runners, and all those activities under equatorial sun generate a lot of heat. Primates, including humans, dissipate heat through the surface of their skin. We can’t really pant like dogs, so we have to lose heat either through radiant heat loss from the surface of our bodies or by sweating. So we evolved the ability to sweat copiously and lost most of our fur.

So early humans in equatorial Africa developed dark skin as protection against the sun?

That’s right. The sun is great, but it has a lot of injurious rays, especially ultraviolet radiation. Most animals protect themselves from UV radiation with fur. What we did in our lineage was turn on pigmentation genes that allowed us to produce more permanent pigmentation in our skin cells. This was really an important revolution in human history because it allowed us to continue to evolve in equatorial environments and thrive and disperse. It really made it possible for us to continue along the trajectory toward modern humans, Homo sapiens, in Africa.

We developed melanin to protect us against the sun. Was skin cancer the main problem?

That probably wasn’t the main problem, although ultraviolet radiation can certainly lead to serious and lethal skin cancer. But this rarely occurs in individuals during their reproductive years, so when we think about the mechanisms of evolution, we have to think about what’s going to be affected during one’s reproductive years. As I was struggling with this problem more than 20 years ago, I realized that one important effect of UV radiation on biological systems is the ability to break down an essential B vitamin called folate, something that we get from green vegetables, citrus fruits, and whole grains. Folate is important for making DNA and new cells. It turns out that ultraviolet radiation has the ability to damage folate and some of the molecules related to folate that are important for our metabolism. The key insight behind our research is that protective melanin pigmentation evolved primarily not to protect us from skin cancer but to preserve our folate so that we could continue to reproduce.

Given all of the advantages of melanin, why doesn’t everyone have dark skin today?

For most of human history, we did. What we see today is the product of evolutionary events resulting from the dispersal of a few human populations out of Africa around 60,000 to 70,000 years ago. Our species, Homo sapiens, originated around 200,000 years ago and underwent tremendous diversification—culturally, technologically, linguistically, artistically—for 130,000 years before a few small populations left Africa to populate the rest of the world. These early ancestors of modern Eurasians dispersed into parts of the world that had more seasonal sunshine and much lower UV levels. It’s in these populations that we begin to see real changes in the genetic makeup of pigmentation. As people move into areas with much lower and more seasonal UV, they run into problems if they have too much natural sunscreen. Some UV is essential for making vitamin D in the skin.

What about differences between the sexes? Don’t men tend to have darker skin than women?

On average, men are darker than women in every population that has been examined. Sometimes this difference is subtle; sometimes it’s greater. Certainly some of it has to do with the physiological needs of the two sexes. Women need to make more vitamin D during their lives, especially when they’re pregnant and breastfeeding, to mobilize enough calcium for their offspring. So they are probably lighter because of this. But we also know that in many peoples across the world there has been a preference for one sex or even both sexes to be lighter colored. In Japan and India, it’s important for a wife to have lightly pigmented or nearly white skin. Where we actually see systematic preference, there’s sexual selection for individuals with lightly pigmented skin.

Wouldn’t it work the other way as well—that women would find men with darker skin more attractive?

Yes, in some cases that’s probably true. In Japan, we know it’s true from sociological studies. In India, however, most groups of men and women select for the lightest possible mates. So we have this interesting phenomenon where not only biological forces but also social forces lead to differences in pigmentation between the sexes or even between groups.

Is skin color still evolving?

Skin color is evolving insofar as we see all sorts of exciting new mixtures of people coming together and having children with new mixtures of skin color genes. If you go into any major city of the world, you see how children are being produced through such felicitous interactions. Not only the pigmentation genes but lots of other genes are getting mixed up. We don’t see much natural selection of pigmentation as we did earlier in our history because we mostly protect ourselves from the harshest parts of the environment—from excess sun or cold or dryness. We’re pretty good at putting on clothes and living in buildings as a buffer against the exigencies of the environment.

If we’re going to talk about skin color, we also have to talk about how we separate people into racial categories. How should we understand race, scientifically?

I think it’s important to understand this from a few different perspectives. When we look at genetic diversity, we can see there are no clean breaks between human populations. Individuals have different groups of genes, so we see rough-and-ready kinds of biological groupings, but these blobs of genetic variation overlap and grade into one another. There are no clear demarcation lines. This is one of the reasons, the primary reason, why geneticists have said there are no human races from a biological perspective.

Every population is unique, and there are some geographical patterns in that variation. The most important of these is the African origin of our species. Only a tiny fraction of alleles, and a small fraction of allelic combinations, is restricted to a single geographic region, and even less to a single population. The diversity between members of the same population is also large. There is extensive sharing of alleles across continents and small genomic differences between populations. This is why attempts to identify races in humans have failed.

How would you define race?

The definition of race depends on what kind of a scientist or observer you are. To most biologists studying races of plants or animals, a race is a population of organisms that can be visibly distinguished from other such groups. Human races have been defined by combinations of anatomical, behavioral, and cultural criteria, and these definitions have varied through time, through history, and from place to place. To most humans, races are creations of the mind that have social reality and that often have physical traits associated with them.

So race is strictly a social construction?

Yes, but that doesn’t make it any less real. When people identify as belonging to a certain group, the biological or philosophical status of the race doesn’t really matter. So race is a very durable construct and people have strong racial identities that are often tied up with physical appearance, but also include a lot of cultural aspects.

But it would seem there are some physical differences between races. For instance, people of West African origin dominate the world-class sprinting competitions.

This raises a very interesting question: Would you put West Africans in a separate race? Most people wouldn’t because their biological characteristics have so much overlap with people from East Africa, where people have tremendous abilities in long-distance running but not in sprinting. You can see concentrations of people with certain attributes, but these attributes overlap with nearby and even distant populations. So drawing a definite line of demarcation becomes impossible. And if you’re looking at a characteristic like sprinting ability, this requires biological ability in a person’s skeletal muscles. It also requires tremendous amounts of training, so there’s a huge cultural component. You can’t have just one or the other.

If our bodies evolved to develop certain differences, such as skin pigment, wouldn’t we also expect variations to evolve in our brains in response to local pressures? So wouldn’t the social behavior of different racial groups also be shaped by evolution?

For over 2 million years, our brains got larger along with the technology we developed to manipulate the environment and our fellow human beings. Over time this process was based on cultural rather than biological innovations, with most of the biological specialization of the modern human brain established before 70,000 years ago, when humans started leaving Africa and dispersing into Eurasia. We can’t rule out the possibility of genetically based specializations of the brain over the last 70,000 years, but this has undoubtedly been very minor.

All modern humans share tremendous abilities to observe and remember and respond with uncanny behavioral flexibility to all kinds of complex problems. The evolution of human skin, by contrast, has really only been affected by cultural evolution in the last 20,000 years, when we see sewn clothing and complex shelters. Before that, skin was the primary interface between our bodies and the physical environment. The tremendous variety of skin colors that we see today owes to local natural selection and also to genetic drift, which restricted the gene pools—and the variation of pigmentation genes—in many small, dispersing populations.

What do you make of studies that have linked IQ and race?

The studies are flawed in the way they’ve been conducted, in the nature of the samples that have been used, in the tests that have been given. The people who have undertaken these studies have gone in with an agenda in mind. This is dangerous, and we know in the history of science that when people come in with an idea they want to prove, this is not science.

There have been studies of relatively small numbers of individuals, with much better controls for educational background, socioeconomic background, and all environmental variables. What these small, careful studies have shown is that there’s no difference in intelligence between the so-called races and that all differences that develop are due to cultural differences. Some of these may be due to differences in diet. Most have to do with differences in learning patterns that result from a child’s cultural framework. In other words, we are all born basically with equal potential and what happens after birth is what really determines our so- called intelligence.

One of the most disturbing historical developments is how blackness became stigmatized around the world. Do we know when people of darker skin color started to be seen as socially inferior?

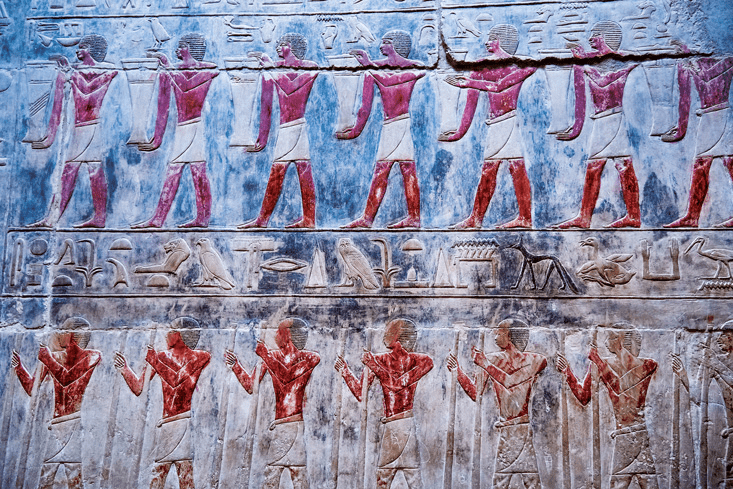

We do. In the earliest recorded interactions between people of different skin color—in ancient Egypt between 4,000 and 7,000 years ago—we see a history of felicitous trading interactions between peoples along the Nile, darkly pigmented and lightly pigmented people trading with one another and having mutual respect for each other’s cultures. In the earliest recorded history of interactions between peoples of different color, we don’t see any prejudicial interaction going on, but simply an acknowledgment of difference.

Some of those ancient societies had slaves, but those slaves were not necessarily dark skinned.

Absolutely. What we see in Greek and Roman societies is that slaves came in all colors. They didn’t share the Greek or Roman culture, so they were considered to be culturally inferior. In Rome, slaves were taken in huge numbers from Eastern Europe to man the agricultural plantations and the mines of the Roman Empire. Slavery was not just for darkly pigmented people. People from Africa were taken as slaves fairly late in the game. Sadly, they became the biggest slave market for a variety of reasons. They could be harvested in large numbers from equatorial Africa through various trading networks. People were also beginning to assign negative personality traits and moral values to their color.

When did this prejudice become widespread?

This becomes really potent in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries and then in a significant way in the 18th century. It’s mostly associated with the growth of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It becomes very important in the history of colonial mercantilism. A workforce was needed to develop colonial lands, and for a long time European traders tried to use European colonists and convicts to meet this need. This was insufficient for the tremendous demand and so, “Well, let’s get some slaves.” It’s very important that you create slaves as an inferior class as people. You dehumanize them by saying they are inherently immoral, inherently incapable of developing true human qualities. They are sub-human. This makes the whole slave trade much more palatable.

There were some influential thinkers who played up these racial differences. Linnaeus, the 18th-century scientist who developed modern taxonomy, separated people into four human races and attributed various temperaments to each. The philosopher Kant wrote about the different races of humanity and claimed that white Europeans were the most talented race. These people helped lay the foundations for the modern world.

Linnaeus was read by Kant, and many people read Kant, including Thomas Jefferson and other thinkers important in the formation of our country. Kant had a tremendous influence on them. They had their own emotionally based opinions about race that they wrote as fact, which complemented the biblical misinterpretations of color. This becomes the most toxic combination in human history. You have blackness associated with sub-human status, on a lower rung of human creation that’s less able to generate a complex civilization. This turns out to be a very potent combination and sadly, one that we’re still stuck with because so much of modern thinking in the United States derives from the late 18th and early 19th century, when these ideas were widely circulated and the trans-Atlantic slave trade was going strong.

Pale skin is clearly not as prized as it once was. How do you see the politics of skin color in today’s world?

We live in a strange world where many light-skinned people want to be darker—or at least tanned to look healthy and like they’ve just enjoyed a vacation on the Riviera. A lot of darkly pigmented people want to look lighter because lightness is associated with higher status. So we have a paradoxical situation where many light people want to be darker and many dark people want to be lighter. Humans are motivated by diverse sets of ideas. They usually aspire to an appearance that confers higher status. Once we recognize that it’s a pretty stupid thing to do, we can adjust our cultural sights and say, “Hey, let’s just live with the skin color that we have. Let’s protect it, let’s cherish it, let’s make sure that we are healthy with it.”

Steve Paulson is the executive producer of Wisconsin Public Radio’s nationally syndicated show “To the Best of Our Knowledge.” He’s the author of Atoms and Eden: Conversations on Religion and Science. You can subscribe to TTBOOK’s podcast here.