When Germanwings Flight 4U9525 crashed into the French Alps in March it did not take investigators long to determine the likely reason: Co-pilot Andreas Lubitz had allegedly been suffering from depression and may have crashed the plane as a means to commit suicide, taking hundreds of people along with him. But that doesn’t tell the whole story; investigators needed to know more. Why was he allowed to pilot a jet full of passengers despite his treatment for mental illness? How did he manage to lock the pilot out of the cockpit? What faults in the system allowed that fatal combination of circumstances to occur?

Such questions have become routine following major accidents. They reflect an understanding that in any complex technological system the human is but a single component, albeit a crucial one. People often blame human error for accidents when they can’t find a mechanical cause. But that’s too simple, as the investigators of Germanwings and other tragedies know; for mistakes rarely happen in a vacuum.

For most of human history, the notion of “human error” did not exist, in the sense of mistakes that cascade into technological accidents. Certainly our ancestors made their share of errors, but there was only so much damage that a slip with a hand tool wielded by a craftsman could do. That changed with the Industrial Revolution: Instead of simply using a tool, the worker also became one in a sense, as a cog in a factory. Under the pressure of repetitive tasks, accidents became common—sometimes serious enough to shut down a production line. Rather than look for flaws in their machinery, factory owners would often blame the human component. By the early 20th century, workplace psychologists were studying so-called “accident-prone” employees and wondering what made them that way. The British industrial psychologist Eric Farmer, who shares credit for inventing the term, devised a series of tests to weed out such people or place them where they could do the least harm.

That view toward human error dramatically changed during World War II, when new technologies were emerging so rapidly that even the least accident-prone human could slip up. In 1943 the U.S. Air Force called in psychologist Alphonse Chapanis to investigate repeated instances of pilots making a certain dangerous and inexplicable error: The pilots of certain models of aircraft would safely touch down and then mistakenly retract the landing gears. The massive aircraft would scrape along the ground, exploding into sparks and flames. Chapanis interviewed pilots but also carefully studied the cockpits. He noticed that on B-17s, the two levers that controlled the landing gears and flaps were identical and placed next to each other. Normally a pilot would lower the landing gears and then raise the wing flaps, which act as airbrakes and push the plane down onto the wheels. But in the chaos of wartime, the pilot could easily grab the wrong lever and retract the landing gears when he meant to raise the flaps. Chapanis’s solution: attach a small rubber wheel to the landing gear control and a flap-shaped wedge to the flap control. Pilots could immediately feel which lever was the right one, and the problem went away. In this case it was clear that the problem wasn’t the pilot, but the design of the technology that surrounded him.

After the war, that kind of thinking made its way into industry and led to the study of “human factors” engineering. The idea was to no longer blame humans, who often represented the superficial cause, but to examine the complicated systems in which they operated. In other words, before the war humans were seen as the cause of error; after the war they were seen as the inheritors of errors inadvertently built into the system. In 1967 the National Transportation Safety Board was established to ferret out such errors: Its “Go Teams” of experts race to a transportation or pipeline disaster to conduct a technical and procedural autopsy. Largely because of this agency’s work flying a commercial airliner is statistically one of the safest things you can do.

Disasters are inevitable, and with each one our understanding of error grows more sophisticated. Experts have learned that it’s not only technology that leads to what appears to be human error, but the culture in which that technology operates. In the wake of the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor, sociologist Charles Perrow developed his theory of the “normal accident”—the idea that certain technologies are so complex, with thousands of interconnecting locking parts and procedures, that accidents inevitably occur. After the space shuttle Challenger catastrophe, sociologist Diane Vaughan produced her theory of “normalized deviance”—that over the years NASA had become so accustomed to seeing flaws in the O-rings that were supposed to prevent flammable gas from escaping that they could not imagine the same flaws would cause a disaster.

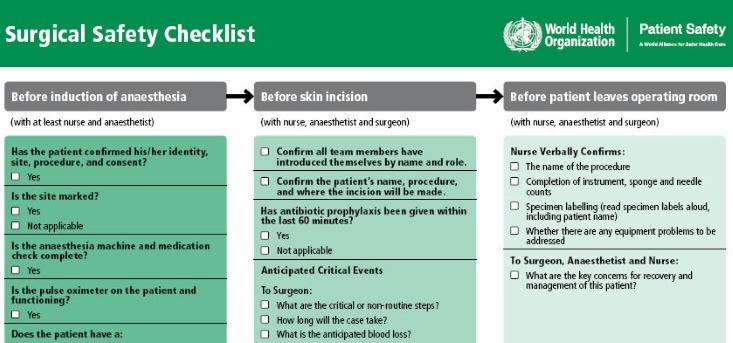

What’s compelling about this kind of thinking is not only its subtlety, but its proactive quality: After all, simply blaming a “bad apple” does nothing to fix the flaws in a system. For that reason, this approach, called root-cause analysis, has made its way into many fields, such heavy industry, fire-fighting, and medicine. A few decades ago, anesthesia was one of the most dangerous medical procedures. In examining the problem, experts learned that they could save lives by tweaking the equipment, such as making that the nozzles and hoses of oxygen and nitrogen incompatible so patients could not be given the wrong gas. The accident rate plummeted to less than a fiftieth of what it had been, according to Lee Fleisher, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Pennsylvania. Some surgeons go through pre-operative checklists, much like a pilot before taking off. That’s what my orthopedic surgeon did a few years ago, as I lay on the table for rotator cuff surgery. He also had the nurse write “yes” on one shoulder and “no” on the other—another redundant safety measure inspired by aviation.

The most provocative new venue for root-cause analysis is the justice system. What could be more blameworthy than a botched prosecution or wrongful conviction? Yet psychologists and legal experts are finding that legal catastrophes are born of multiple factors, rather than a single overzealous prosecutor or misguided cop. Consider the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. No one imagines that officer Darren Wilson woke up that morning and decided to shoot an unarmed teenager. And so we should ask—what previous decisions and policies presented him with that choice in the first place? Was he equipped with non-lethal weaponry? Was he trained in de-escalation? Should he have had a partner in his squad car? To what degree did racism and revenue-based policing, as cited by the U.S. Department of Justice, set the stage for that tragic event?

“It’s not just the cop or the prosecutor,” says James Doyle, a prominent defense attorney who is leading a nationwide effort to bring systems analysis to police departments and courtrooms. “It’s also the people who set caseloads and budgets; who created the huge pressures that other people have to adapt to.”

That’s not to excuse people like Wilson or Lubitz, whose actions have caused harm. But to really get to the root of any tragedy it’s important to see ourselves as we are—imperfect beings living in webs of complex social and technological systems. Some humility is in order before we assign blame.

Douglas Starr is co-director of the graduate program in science journalism at Boston University. His books include The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science and Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce.