In 1983, Yosef Eckstein an ultra-orthodox rabbi in Brooklyn, New York, had reason to be happy: His wife had just given birth to their fifth child. But the couple’s happiness was short-lived: The child was soon diagnosed with Tay–Sachs disease, a genetic disorder that affects the nervous system. Over time, the child would experience developmental delays, become paralyzed, and die before the age of five. This was the Ecksteins’ fourth child born with the disease, which was typically only found in one of every 3,600 children born to Ashkenazi Jewish families.

The couple was heartbroken, but since Tay–Sachs is passed on through genes and ultra-orthodox, or Hasidic, Jews don’t allow abortion, they felt there was nothing they could have done. Eckstein learned about efforts in the larger Jewish community to reduce the prevalence of Tay–Sachs disease by doing genetic tests for couples before they had a child, but it hadn’t caught on in the Hasidic community, mostly due to mistrust of the outside world and the stigma a diagnosis could bring to a family. (See Alexandra Ossola’s previous post on testing for Tay–Sachs among Ashkenazi Jews as a whole.) So Eckstein developed a genetic screening program that would prevent two Tay–Sachs carriers from having children, thereby reducing the prevalence of the disease, while keeping the results as discrete as possible. He called it Dor Yeshorim, the righteous generation.

At the time, the Hasidic community in the New York area was the largest in the world. (Today it’s surpassed only by the community in Tel Aviv, Israel.) These fervently religious groups wear traditional clothes that harken back to Eastern European styles of a few hundred years ago, and they strive to follow much of the legal framework set by the Bible’s Old Testament. The community remains fairly closed, mostly living and socializing amongst themselves; marriages between young people in the community are arranged through a shadchan, or matchmaker, and most are married by age 20. And though many orthodox Jews consider it an important duty to care for one’s physical wellbeing, even their relationship to health care carries a religious component, as many individuals seek counsel from their rabbis before seeing a doctor. With few exceptions, Hasidic Jews also reject birth control and abortion.

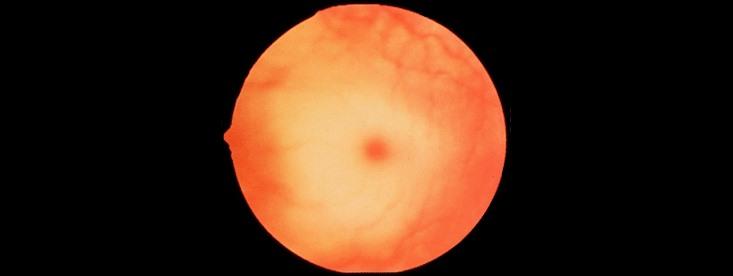

All of these factors made it harder for Eckstein to start to purge Tay–Sachs from the community. But the challenge he was most concerned about was the stigma surrounding the disease. Tay–Sachs is caused by recessive genes, so parents who carry the gene have no indication until they have a baby with the disease or they get a genetic test. Eckstein knew that the traditional community’s attitude toward birth control wouldn’t allow for the approach used by some people in the mainstream world: in vitro fertilization, pre-implantation genetic testing, and abortion. And he was wary of the stigma that might be attached to families trying to match their offspring in marriages—if a family was trying to find a wife for their son, he might be seen as less desirable if the entire community knew that Tay–Sachs runs in their family.

So Eckstein devised a way to screen for the recessive gene while still keeping the results anonymous. High schoolers who were not yet engaged would have a blood sample drawn for the DNA test. But they would never see their results—instead, the results went to Dor Yeshorim, while each person would receive an identification number. Later on, when a marriage was proposed, the families or the shadchan would call the Dor Yeshorim hotline with the two anonymous identification numbers for the potential couple. If one potential mate or neither of them were a carrier, the hotline operator would say it was a good match; if both people were carriers, the operator would say it was a bad match. Couples could still proceed with the engagement if they chose, but they would be forewarned that their children might be born with the lethal condition. They would also receive genetic counseling to help in those choices.

To Eckstein’s credit, the program has worked and continues today. Each year, Dor Yeshorim screens about 20,000 individuals in over 400 schools worldwide, for Tay–Sachs as well as a slew of other genetic diseases, including Gaucher’s disease and cystic fibrosis, neither of which is curable but can be well-managed with treatment. So far, Dor Yeshorim has advised 4,200 couples not to marry based on the results of the test, most of which took the advice and broke off the match. As a result, Tay–Sachs has become much less prevalent in Hasidic communities; the Tay–Sachs ward at Kingsbrook Hospital in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, which once had a waiting list of patients, has permanently closed, and the disease is now more common in non-Jewish families than among Jews.

Despite the positive results and his efforts to avoid ruffling the community, Eckstein has not been immune to criticism. As Dor Yeshorim has tested more people and expanded to include more diseases, some have accused Eckstein of practicing eugenics or “playing God.”

Even the greatest proponents of Dor Yeshorim understand that the program was likely successful because it was limited to such a clearly defined population where marriages were arranged at such a young age. “Would it work for the larger community? Probably not,” says Karen Litwack, a senior advisor for educational initiatives at the Center for Jewish Genetics in Chicago. “In the general community people choose their own spouses and don’t use the go-between. People want to be able to make their own decisions based on knowledge, so it makes sense for them to receive their results [of a genetic test].” But Litwack is wary of expanding the Dor Yeshorim testing to dominant genetic traits within the Jewish community, such as the BRCA breast cancer genes. She says those sorts of tests don’t help parents make informed decisions about family planning because many conditions are treatable and most are less severe than Tay–Sachs.

Others outside the Hasidic community see the powerful community engagement that has made Dor Yeshorim a success, and could do the same for other conditions that are as damaging as Tay–Sachs. “[Eckstein and his collaborators] built upon personal experiences and urged individuals to do something about what they as a community agreed was a problem,” says Julia Inthorn, a medical ethicist at Göttingen University in Germany. As genetic testing becomes more common, researchers will uncover more genetic links between particular populations and diseases—Dor Yeshorim, Inthorn says, could set the standard for how communities start to talk about these issues. “We really need to understand why some genetic screening efforts are so successful—less so in the medical aspect, but more about how communities are integrated into the development of a genetic screening program.” Understanding the forces underlying community decisions, as Eckstein did, may hold the key to lowering the prevalence of many other genetic diseases in the future.

Alexandra (Alex) is a science writer. Currently based in New York City, she has previously lived in Brattleboro, Vermont; Lima, Peru; and Washington, D.C. She tweets at @alexandraossola.