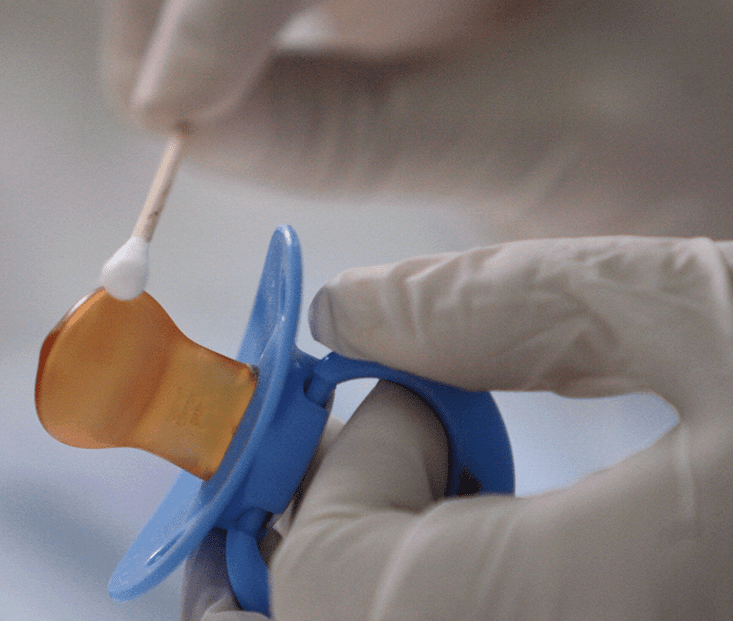

Who’s your daddy? It’s a fair question. A meta-study published in 2006 by a University of Oklahoma anthropology professor estimated that 30 percent of men who have low paternity confidence about a child were justified in their suspicions. Even among men with high paternity confidence (that is, they’re married to the mother), about 2 percent were cuckolds.1 During the eons before reliable paternity tests became available in the 1960s, there was no way to verify these “non-paternal events”; even the mother could only guess. Today anyone can submit a few hundred dollars and a scraping of their cheek cells and, if the older guy who claims to be the father does the same, within weeks confirm or deny that claim. Predictably, that 2 percent margin of error has led to some uncomfortable situations (see Genetic Surprises).

DNA testing has become very popular among genealogists. The birth certificates, census records, and other documents they usually rely on can be wrong. DNA is never wrong. It can’t be altered, or forged, and you can’t misfile it. You can’t even always destroy it: DNA has been recovered from a frozen, 5,000-year-old corpse and used to identify his living descendants.2 Genetics do not uncover everyday family secrets such as the fact your great-great-grandfather owned slaves (unless he fathered children with some of them) or that a great uncle flunked out of West Point—it reveals the family secret, from whence you came, your begat. And your tree very likely has some invasive branches. As you look further up the tree, the chances of a non-paternal event rise exponentially. After 10 generations, you have 1,024 ancestors—I’m telling you, someone strayed. That’s why it’s prudent to trace families, not pedigrees.

You read these alarming stories once in a while about men who were first enthused about testing but then troubled when they discovered they aren’t who they thought they were, at least biologically, or that they have a half-brother they didn’t know about, or that an unsuspecting, elderly uncle doesn’t match any other male in the family (do you break it to him?). A hyperventilating, cautionary report posted last year at Vox.com trumpeted that genetic testing can unexpectedly tear families apart with revelations that are especially painful “when users aren’t looking for them in the first place.” As the databases at testing sites such as 23andMe grow, it warned, “there will be more and more family reunions, many of them by users who have no idea they are coming and aren’t prepared for them.”3 The article was accompanied by an essay by a reproductive biologist who had submitted his Y-DNA and that of his father for analysis. After the samples were processed, “George Doe” and his father both opted to see close matches. As George recounted, a user identified only as Thomas was shown to be a 50 percent match to George’s father—a son. George’s father professed to know nothing about Thomas, but George said the revelation unleashed “years of repressed memories and emotions,” presumably because Thomas had been conceived during an affair.4

If a child is found to have a higher risk of skin cancer, can a parent be compelled to keep the child away from the beach?

The Vox report irritated Blaine Bettinger, who blogs as The Genetic Genealogist. He argued it unfairly castigated DNA as a home wrecker. After all, Bettinger pointed out, census records, birth certificates, wills, and many other records also have the same potential. Bettinger discovered this himself when a state census revealed his great-grandmother was adopted, a fact that affected more than 60 living descendents. (Should he have been warned by the census bureau that the data he was requesting was dangerous?) Further, most people are not devastated but overjoyed to discover lost siblings, or birth parents, or re-connect with children given up for adoption.5 Startling tales of discovery are also extremely rare: while Vox reported that some 7,000 users at 23AndMe “have discovered that their parents weren’t who they thought they were, or that they had siblings they never knew existed,” a 23andMe spokesman told me that calculation was based on a guess that about 1 percent of its then-700,000 users had discovered a relative they didn’t know about, and that discovering distant cousins was far more common than anything about parents or siblings. The lost relative must also be a member of the site, which makes a match all that more unlikely.

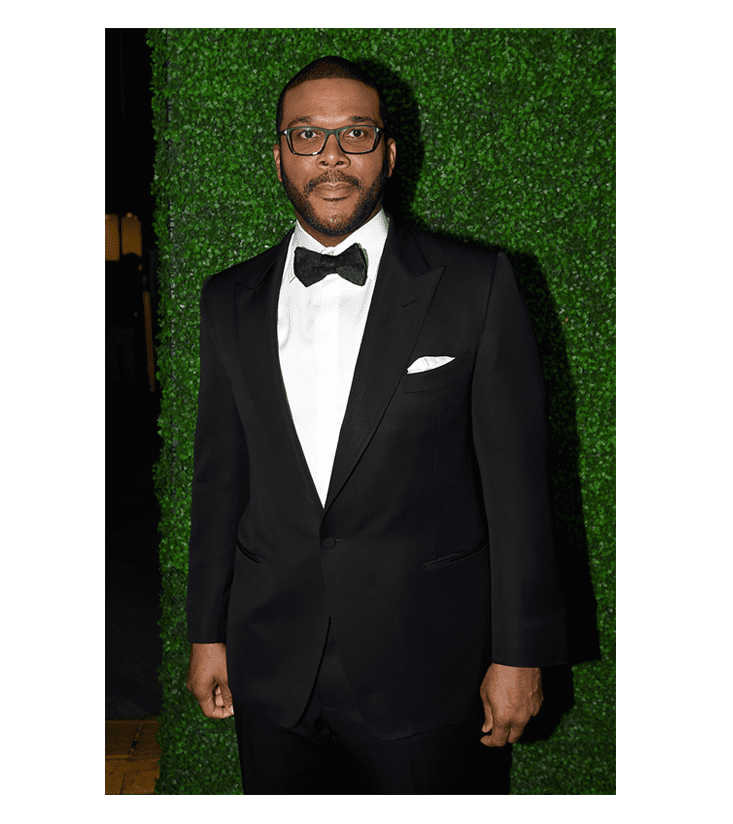

* The comedian and director Tyler Perry was originally named Emmitt Perry, after his father, although his father was so abusive Tyler wondered about the relationship. His mother reassured him, but after her death, Perry tested his Y-DNA and found it did not match his brother’s. He confirmed the family secret when his father was tested and matched Tyler’s brother but not him. He is now searching for his biological father.

* A Pennsylvania doctor named Mark Hudson discovered in 2005 through Y-DNA testing that his 12-year-old son was not his. Hudson left his wife but was ordered to pay $1,400 a month in child support. “I still feel like he’s my son,” he told a reporter. “But I think it’s wrong to enrich the person who committed the fraud. The child deserves the truth.”

* Alan Cumming, best known for his role in the X-Men films, had a troubled relationship with his father. They had not spoken for 16 years when his father revealed that Alan wasn’t his son. He said Alan’s mother had cheated with a family friend, whose name he provided. Cumming was devastated but also wary, so he had Y-DNA tests done that proved he was, in fact, his father’s son. “Whatever the results of the DNA test, even before that, I didn’t think I was my father’s son,” Cummings has said. “I marvel at the fact I am related to this person.”

Bettinger labeled Vox’s sky-is-falling approach as an example of “genetic exceptionalism.” The term caught my eye because I hadn’t seen it in a long while, and never in relation to genealogy, only medicine. It was coined in 1997 by a bioethicist named Thomas Murray to describe the fallacy that our genetic code is so powerful it deserves special protection beyond that given to other kinds of personal information.6 The phrase is a play on the earlier idea of “HIV exceptionalism”—that HIV status needed to be locked behind two steel doors because of the enormous potential for discrimination. While geneticists generally don’t subscribe to the notion that genetic information is exceptional (unless hyping their own research to secure more funding, perhaps), the public is another story. According to public opinion surveys, we vastly overestimate the predictive power of genetics. For instance, in a 1990 survey, 55 percent of respondents believed incorrectly that genetic testing could be used to “predict whether or not a person will have a heart attack.”7 Even as late as 2010, half felt “all children will be tested at a young age to find out what disease they get at a later age.” Further, 38 percent believed a class system would soon develop between those with “good” and “bad” genetic dispositions.8 The public frets especially that employers and insurance companies will use genetic tests to fire them, or hike their rates, or deny coverage. They fear insurers and employers will embrace the power of genetics and use it against them, because those groups believe in the same power—an infinite loop of ignorance.

James Evans, a geneticist at the University of North Carolina, specializes in public policy and attitudes toward genetics. Genetics are indeed powerful, he told me, in that they are “at the heart of our most profound relationships.” (Genealogists would agree.) But too many people believe they define who we are by “determining” our personality, intelligence, appearance, behavior, and health.

C. Thomas Caskey, a doctor at the department of Molecular Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine recalls one example. A young patient visiting his clinic was found to have mutations in BCRA1 that are associated with a fast-growing type of breast and ovarian cancer. The woman had an elderly aunt who had survived breast cancer, and the doctor suggested the aunt be tested for BRCA1. The aunt refused, saying she didn’t want to know because if she had the gene, she might have to tell her daughters they were at risk. Caskey found that attitude unfortunate but not surprising. The aunt may have associated telling her daughters about BRCA1 as the equivalent of a diagnosis of cancer, yet most women with these mutations in BCRA1 never develop breast cancer. The gene is not a death sentence.

The idea that genetic testing somehow reveals dark, infallible secrets about the future puts pressure on politicians to do something about it. Although genetic testing is protected, like medical data, by privacy laws, many states have passed laws that treat genetic test results as super-double-special secret. Congress brought them all together in the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, which is aimed specifically at employers and insurers. (Notably, long-term disability and life insurance are not covered by the law, so those providers test you for whatever they want. There are also no laws protecting your genealogical data, although sites that provide these services all have privacy policies, however binding those may be.) Ironically, genetic privacy laws discriminate in their own way by singling out people whose diseases can be tied to genetic risks. As two Georgetown law professors wrote in 1999 about state laws: “Why, for example, should medical information about a woman who has developed breast cancer of genetic origin … be given greater protection than a woman who has developed breast cancer because of environmental or behavioral factors (e.g., smoking)?”9 Besides, the professors added, genetic test results usually tell a doctor far less about future risk than a patient’s sex, age, race, occupation, financial status, employment status, and family history—all of which receive only “ordinary” protection from prying eyes.

Scientists deserve some blame for these misconceptions about the power of DNA. “Since the 1950s at least, molecular biologists have been prone to talk of DNA … as containing genetic information,” the British bioethicist Neil Manson has written. “But this is to use ‘information’ in a causal sense: … specific DNA sequences (in the right context) will cause those traits or bring about the production of those proteins.”10 In other words, genes don’t operate in a vacuum; environmental influences play a huge role. (It’s worth noting that epigenetics, which studies heritable trait changes not caused by changes in genes, has its own exceptionalist discussion.11) But that’s not always what you hear. James Watson, one of the discoverers of the double helix, said, “We used to think our fate was in the stars. Now we know in large measure, our fate is in our genes.” In 1993 George Annas, a health lawyer at Boston University, described our genes as a “future diary.”12 That shorthand got him in trouble, he told me recently, with some colleagues accusing him of coming off as a “determinist,” which is a geneticist’s way of calling someone a simpleton.

Annas was and is deeply concerned about the potential bureaucratic abuse of genetic markers, and contributed to the 2008 federal privacy law.13 If a child is found by a child protection agency to have a higher risk of skin cancer, he asked in 1993, can a parent be compelled to keep their child away from the beach? Or, as the cost of sequencing an individual’s genome drops (it’s now less than $1,000), will universities ask for samples to check applicants for markers of sufficient intelligence? How about those that point to early death, since so much is being invested in the person’s education? And what about our obligations and responsibilities when it comes to sharing genetic data? Annas told me he believes parents should be prohibited from testing their fetus or child for genetic markers unless there is a way to prevent or cure the disease before the child turns 18. Otherwise, it’s nobody’s business but our own. (Annas concedes, given the legal power parents have over their children, this prohibition is unlikely to happen.)

That’s like saying that because a woman is born with eggs in her ovaries she has a pre-existing pregnancy.

The problem with this line of thinking is a simple one: As the geneticist Eric Juengst has written, genetic testing is not fortune telling, but a weather map, a fallible tool.14 I’m sure health insurers would love to codify genetic exceptionalism and treat specific genes as “pre-existing conditions,” but that’s like saying that because a woman is born with eggs in her ovaries she has a pre-existing pregnancy. “The identification of a risk marker is not a disease,” Caskey explains. “Everyone has five to 10 recessive traits, including some that are potentially very severe.” Further, studies have shown that even if you combine several risk factors for any particular illness, it can’t tell you or a doctor what will happen. As Evans pointed out in one study: “The lifetime risk for an individual in the United States to develop Crohn’s disease is about 1 in 1,000. How helpful is it for clinicians and patients if that risk shifts to 1 in 500 or 1 in 2,000?”15 There is also no evidence that knowing you have a genetic marker (or a lack of one) changes behavior. Finding out their genetics suggest a decreased risk for diabetes doesn’t send most people on a sugar binge.

Further, there is no “gene for Alzheimer’s” or “gene for breast cancer.” Researchers were focused on single genes early on but have shifted focus to arrays of genes and how they conspire with each other and the environment, rather than scanning for lone assassins in the crowd. For example, the suspicion now is that some people who have a gene associated with a certain disease but never develop it may have other genes that suppress the first one. Gene mutations have been found that prevent HIV from entering cells, reduce the amount of bad cholesterol, or offer partial protection against heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. One effort to find healthy people with genes that increase their propensity for fatal diseases is called The Resilience Project. The researchers analyzed the genetic code of 500,000 test subjects and found 20 people who seem to fit the criteria. One example is Doug Whitney of Port Orchard, Washington, who has a genetic mutation associated with Alzheimer’s. That disease killed his mother and nine of her 13 siblings, most of whom had died by their mid-50s. Whitney is 65 and healthy—and quite popular with geneticists.

You also can’t ignore the role of chance. Earlier this year researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine concluded in a paper published in Science that random mutations in otherwise healthy stem cells may account for two-thirds of the risk in whether a person gets the deadliest types of cancer. (Notably, the study did not look at breast or prostate cancers.)16 “If you go to the American Cancer Society website and you check what are the causes of cancer, you will find a list of either inherited or environmental things,” the lead researcher, Cristian Tomasetti, told Science. “We are saying two-thirds is neither of them.” The researchers said they hoped the results would help people calm down about whether every little lifestyle choice was going to give them a tumor. On the other side of that coin, the fact that so much cancer occurs because of random mutations may mean you can’t do anything to prevent it. Sometimes you’re just unlucky.

It’s been just 12 years since scientists finished sequencing the 3 billion DNA letters in the human genome. It is going to take more time for the public to gain a more nuanced view of what genes are and do—and this includes me. Recently I noticed a store greeter dancing and singing and being generally peppy and optimistic, in distinction to my own default state, which is glum resolve. Yet even after having spent a few days talking with geneticists, after which I should have known better, I thought to myself, “He must have happy genes.”

Chip Rowe is a writer based in New York.

References

1. Anderson, K.G. How well does paternity confidence match actual paternity? Evidence from worldwide nonpaternity rates. Current Anthropology 47, 513-520 (2006).

2. Ermini, L., et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tryolean Iceman. Current Biology 18, 1687-1693, (2008).

3. Belluz, J. Genetic Testing Brings Families Together—And Sometimes Tears Them Apart. Vox.com (2014).

4. Doe, G. With Genetic Testing, I Gave My Parents the Gift of Divorce. Vox.com (2014).

5. Bettinger, B. A Response to the Genetic Testing Article in Vox. Thegeneticgenealogist.com (2014).

6. Murray, T.H. Genetic Exceptionalism and “Future Diaries”: Is Genetic Information Different From Other Medical Information? In Genetic Secrets: Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality in the Genetic Era Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (1997).

7. Singer, E. Public attitudes toward genetic testing, Population Research and Policy Review 10, 235-255 (1991).

8. Henneman, L., et al. Public attitudes towards genetic testing revisited: comparing opinions between 2002 and 2010. European Journal of Human Genetics 21, 793-799 (2013).

9. Gostin, L.O. & Hodge J.G. Genetic privacy and the law: an end to genetics exceptionalism. Jurimetrics 40, 21-58 (1999).

10. Manson, N.C. How not to think about genetic information. The Hastings Center Report 35, 3 (2005).

11. Rothstein, M.A. Epigenetic exceptionalism. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 41, 733-736 (2013).

12. Annas, G.J. Privacy rules for DNA databanks: Protecting coded “Future Diaries.” Journal of the American Medical Association 270, 2346-2350 (1993).

13. Annas, G.J. Drafting the Genetic Privacy Act: policy, and practical considerations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 23, 360-366 (1995).

14. Juengst, E.T. FACE facts: Why human genetics will always provoke bioethics. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 32, 267-275 (2004).

15. Evans, J.P., Meslin, E.M., Marteau, T.M., & Caulfield, T. Deflating the genomic bubble. Science 331, 861-862 (2011).

16. Tomasetti, C. & Vogelstein. B. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 347, 78-81 (2015).