In 1984 I was on an expedition outside the barrier reef in New Caledonia, an archipelago 750 miles east of Australia. The expedition was formed to study the daily migrations of the nautilus, the longest-lived animal survivor known to science. I was accompanied by, among others, Mike Weekley, a 26-year-old marine biologist, who had worked at the Waikiki Aquarium. Mike was a veteran of nautilus research trips, seemingly fearless, and an expert diver.

On our fifth day of research, we saw thieves approaching one of our holding cages, roped to a buoy, where 10 nautiluses were being kept for future experiments. Nearby, tied to the reef edge, a long piece of rope stretched down to a deep cage, where we were performing a crucial experiment: What was the maximum depth at which the nautilus could empty its chamber?

From a mile away, we set off for the pirates, with our French captain loading his rifle. But the thieves had a fast boat. We were still a half-mile away when we saw them lift the buoy of the first cage. Had they discovered the other rope? Mike and I quickly hit the water. Both the rope and deep cage were still there. As I dove deeper to check the rope for wear, Mike’s job was to keep any aggressive white-tip sharks off my back. After five minutes, I turned to motion to Mike, who was supposed to be only a few feet behind me. But when I turned there was no Mike. Only an almost imperceptible “hoot” from below me.

The water in the New Caledonia reefs is crystal clear. Looking down, I saw a small human-like form impossibly far below me, a stick figure, motionless. I powered down past the 100-foot mark of a nearly vertical reef wall, seeing the still figure come ever clearer. I could feel my heart pounding, feel my fear. I willed the shape to move. As I passed the 200-foot mark, nitrogen in my brain smashed me with narcosis. When I reached Mike, he was resting in black coral, like a child held carefully in a mother’s arms. I saw that his regulator was not in his mouth and I pushed it back in, hoping he would breathe. It all seemed like a joke, but when I looked into his eyes, I saw the truth, I saw life, I knew that somewhere in his brain he was silently screaming in fear and terror, some parts of him not yet dead.

I pulled Mike from the place he had settled and headed up, trying to squeeze out any air in his lungs before it would expand. It was for naught. The ascent burst his lungs.

Two hours later, in the emergency room of a New Caledonian hospital, Mike lay dead on the tiled floor. His would-be rescuer, and possibly his killer, lay naked, wetsuit cut away and copious amounts of blood being pumped out of his stomach. I had involuntarily swallowed blood while doing mouth-to-mouth and heart massage to Mike for what seemed like eternity on the dive boat. I never learned why Mike sunk to the bottom. It is the nightmare of all divers, a sudden loss of consciousness, or a sudden stoppage of the heart, possibilities even for a young man.

I spent the next year on crutches. My left hip, shoulder, and ankle had been destroyed by nitrogen bubbles. In the decades that followed, the left side of my skeleton has become increasingly made of titanium, ceramic, and rubber, as doctors robotized me, joint by necrotic joint.

Tragedy changes a person. The nautilus had made me a scientist. Yet that same animal caused the death of a close friend. Was his death due to chance, or the human equivalent of bad genes—and, if genes, Mike’s or mine? How could it be explained?

In his book Wonderful Life, the late, great paleobiologist Stephen Jay Gould argued that chance has had the single greatest influence on the history of life. He wrote about a thought experiment that he called “replaying life’s tape.” It was an illustration of how unlikely it would be for the biota of Earth to re-evolve in the same fashion that it has over the past almost 4 billion years. Recently, as I have begun to look back at my lifelong preoccupation with Nautilus pompilius, better known as the Chambered Nautilus, I have begun to replay my own tape and see how a series of random, chance events have directed my own life and career.

For 25 years the overarching theme of my work as a paleobiologist has been a need to know the identities of which species lived, and which died, in the great mass extinctions, the five intervals in geological time, going back 540 million years to the dawn of animal life, when a majority of species were killed off. I have been able to tell a very plausible evolutionary story about how the nautilus has survived over 500 million years by sidestepping the dinosaur-killing asteroid and every other menace the earth and cosmos have thrown it. It was not because it was especially adaptable, it was because it had the incredible good fortune to prefer deep waters and a metabolism suited to life in the slow lane.

But there is one chance element that I never foresaw in my field notes. Humans—present on Earth only because the dinosaurs died out—find the nautilus, with its mother-of-pearl interior, and tiger-striped outer coloring, so beautiful, and so suitable for jewelry, that they are managing to do what mass extinctions never could: drive the nautilus to extinction.

In recent years I have contributed to the breakthrough discovery that ancient Nautilus pompilius is in fact many separate species, which has overturned the widespread reference to it as a “living fossil.” Yet the human toll on the nautilus may be the last discovery that I ever make about this remarkable animal. Looking back at the myriad decisions, tests, detours, and the rest of the messy contradiction and actions that we call life, I have to marvel at the waves of chance that swept the nautilus and me into its rough seas.

My scientific journey, now professionally far nearer its end than its beginning, has been more akin to a pinball descending through a field of random bumpers than some ordained conclusion. And not just in the positions I won (and lost), or the books and papers I wrote, or had rejected. The very topic of my research came into my life by a combination of random events combining with a newly grown tool (the brain and body of a young boy) capable of reacting to chance influence and being transformed by it.

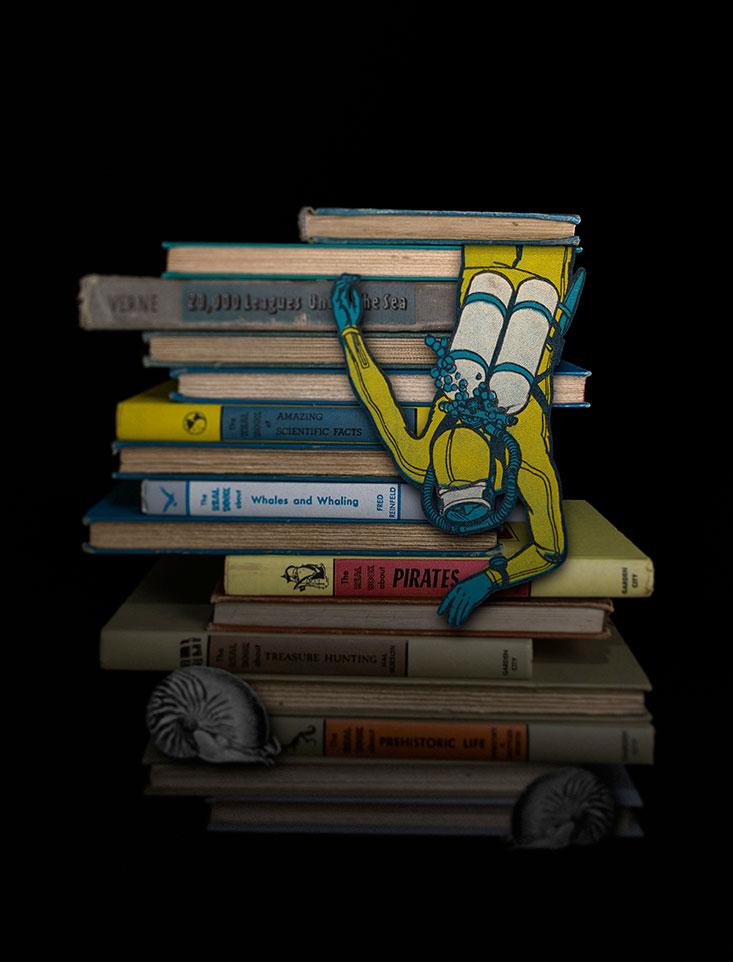

My journey began with the 1954 Disney movie 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea—the first movie I ever saw on a big screen, at the ripe old age of 5. The star of the show was the submarine, or rather Disney’s rendering of the storied craft at the center of Jules Verne’s tale: a surprising shape of curves and straight lines, an extended diamond of a ship exuding strength and speed, difficult to remember in detail beyond an inchoate vision of grace. Much of the movie took place underwater, a highly romanticized underwater at that. Growing up next to Washington state’s Puget Sound, with its wonderful tide pools and salmon, whales and seabirds, was itself an invitation to love science and marine biology.

This dual love of a shape and place—submarine and the ethereal underwater world it owned—was soon augmented by an even more seductive shape. In 1956, on a trip to Hawaii, I was suddenly confronted by the real thing: the chambered nautilus. The shell shop was on a quiet corner, a block from the beach. I moved from display to display, pleased by the cornucopia of shapes and exuberant colors that the tropical mollusks possess. With its beguiling curves and chambers, the whole proclaiming a mathematical embrace of function by form, I was hypnotized. In this I know I am not alone. Many of my colleagues who study ancient nautiloids and their cephalopod cousins, the beautiful and extinct group of swimming animals known as ammonites, have confessed to falling under a similar spell.

My job was to be in the water with the whales and separate mothers from their young. The going price for an orca was $50,000. I was paid $50 a day.

My obsession was further stoked in 1958, when the world’s first nuclear submarine, the USS Nautilus, made the first transit beneath the ice-covered North Pole. Soon I was doodling the damned spiral with its regularly increasing chambers on every school paper, and was probably certifiable. Nautilus, nautilus, nautilus. What emerged was a merging of submarine and romance, a witchcraft induced by three different nautilus submarines: one celluloid, one biological, and one armed with torpedoes. My course was set. Here was a living submarine, wrapped in mystery, inhabiting the Pacific in the hallowed places where my father had fought a bloody war a decade earlier, a creature linked to dinosaurs and the undersea. What better star to become attached to? All I had to do was get good enough grades to get into college, not flunk out and get sent to Vietnam to be killed or maimed, as so many who did wash out of organic chemistry class were, get into grad school, and end up as a professor at a major research university. Because any number of things could have easily ended my quest, it is quite apparent that luck was my guardian angel. Sheer luck on the scale of winning a lottery.

Because the nautilus lives in the sea, I needed to be water-wise and water-tested. I had the great fortune to grow up on a lake. A 15-foot dive to its muddy bottom, required in the games of sponge tag that the gang of boys in my neighborhood endlessly played, taught me to respect rather than fear water. From early on I was un-flummoxed by being in the dark, cold wet. At age 16, I built a scuba tank out of an old fire extinguisher bottle, acquired a $15, used regulator and an old hand-me-down (and piss-stinking) wet suit, and began diving in Puget Sound after a single scuba lesson. I went on to teach and certify more than 1,000 people to dive, while putting myself through college as a commercial salvage diver, which led me to one of my most fateful jobs: a diver for Sea World, catching live killer whales.

In 1970 and 1971, I was part of the infamous Penn Cove (Washington) whale hunts. At that time the Puget Sound region, or its salmon-fishing community, despised the orca, which routinely ate half the salmon returning each year to spawn. Trapping was applauded. We encircled pods of 30 to 40 whales with seine nets thrown from fishing boats, and culled and captured with ropes the babies for aquaria. My job was to be in the water with the whales and separate mothers from their young. (I once found my leg down the throat of an enraged mother, who spit me out). Rumor had it the going price for an orca was $50,000. I was paid $50 a day.

But another part of my job was to dive down into the seine nets at night, should the whales try to break out. During those nights I learned more about fear than I ever wanted to know—down 40 feet in low visibility, with a dive light in one hand and a knife in the other to confront the poorly seen but certainly felt struggles of a gigantic, multi-ton behemoth fighting for its life in a heavy net, its massive tail thrashing through the blackness. We mostly succeeded in cutting the whales loose from the nets. But not always. That brought about shame, followed by rage, at myself, and at the greedy, voracious men who then, as now, make money from the incarceration of these intelligent creatures.

Following an expose of the hunts by Seattle TV news reporter Don McGaffin in 1971, some of my fellow divers and I testified to state authorities that our employers had been covering up evidence of whales killed in the hunts. Our proof helped launch a state and then federal law to prevent capturing whales in U.S. territorial waters and giving them a life sentence in solitary confinement. It remains the most important work of my life: helping stop the obscene captures.

Nautilus lives in the sea. It also lives in the past. In college I pursued a course of study that married marine biology with paleontology. I was admitted into graduate school in geology (I earned my Ph.D. at McMaster University in Ontario) and conducted studies that got me as close to the nautilus as academics could then go—the study of fossils. I waited and watched and hoped that chance would provide me entrée into my real dream, the chance to study the living nautilus in the wild.

My lottery number came up in 1975. One spring day I happened to be on the University of Washington campus, when I saw a poster announcing a scientific talk to be given by a hero of mine, the great physicist-turned-marine biologist Eric Denton, of the famous marine laboratory at Plymouth, England, about the nautilus and buoyancy.

Since the nautilus first came to the attention of European naturalists in the 1600s, there was intense speculation on how it used its chambered shell to attain weightlessness. For almost four centuries it was believed that when each new chamber was formed, the animal secreted gas into it. It was the same principle, or so it was thought, used by submarines: Gas pumped into ballast tanks generates buoyancy.

But Denton, working in large buckets and tide pools on the tropical island of Lifou in the mid 1960s, discovered that each new chamber, sequentially produced by a growing nautilus, was filled with a saline bodily fluid, not gas like a submarine. Through osmosis, carried out by a permeable siphuncle, which spirals through the shell’s chambers, the nautilus pumps salt ions from the chamber liquid, causing the “fresher” liquid to be secreted as urine. While gas, circulating in the nautilus’ blood, diffuses back into the chamber, it has no effect. It’s the liquid leaving the chamber that grants the nautilus its famous weightlessness. Denton and his colleague John Gilpin Brown did show that the name nautilus was appropriate for the animal and submarine in one sense: both have the same design flaw—a finite depth at which both are crushed by too much pressure. In the sea creature’s case, about 2,500 feet.

The development of buoyant shells by the nautiloid was one of life’s great evolutionary innovations. Some 500 million years ago, the time before fish, all animal life lay on the ocean floor. Then along came an animal that could “float” in the water. For the first time a mobile carnivore could descend on its prey, with eyes and sensory apparatus that could look ahead but never up. For the crustacean-like trilobites, the main prey of the first nautiloids, it was slaughter.

The nautiloids were probably the smartest creatures in the sea. When they evolved from snail-like ancestors, more than 520 million years ago, they were energetic, thanks to enormous gills and a new kind of blood pigment, the copper-based haemocyanin (oxygenated nautilus blood is blue). With all that oxygen coursing through their bodies, a new type of organ became possible: a large and perhaps calculating brain, certainly the highest level of intelligence seen in the animal world up to that point. Nautiluses also carried a lethal weapon—parrot-like jaws with cutting edges capable of slicing through arthropod exoskeletons. With brains and brawn, the nautiloids ruled the seas for millions of years.

Between 2007 and 2010, more than half a million nautilus shells or artifacts—cheap jewelry—were imported into the United States alone.

In the audience at Denton’s talk was a University of Washington professor, Arthur Martin, who had managed to acquire funds to travel to New Caledonia that summer to study the nautilus in the fabled Aquarium de Noumea, the first aquarium to maintain living coral, and the first to put the nautilus on exhibit. By chance I overheard Martin asking Denton for advice on the Aquarium, where Denton had done pioneering work. With heart in throat, I interrupted the pair and invited myself to accompany Martin to New Caledonia as his assistant, volunteering to find the money to pay my way on the three-month trip.

New Caledonia is the only place on Earth where nautilus swim in water shallow enough for a scuba diver to see them. On dark nights, I was able to follow them in their native habitat, the first scientist to ever do so. With a tough, ex-military French buddy, I spent many nights diving outside the vast reef that parallels the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. Every night we would spend an hour stabbing through the clear water with our dive lights, our probes reaching into the blackness, illuminating the white shells of the ascending nautilus. We would follow them, on moonlit nights with our lights off, as they swam right into the surf zones of the shallowest parts of the outer barrier reef. Their forays into the shallows was to find food—not live food, we learned, but fresh molts of lobster. That was a surprise. The nautilus, it turns out, is an obligate scavenger, and can find carrion from many miles away, thanks to an exquisite olfactory system.

Our research paid off in other ways too. I learned how the nautilus had lived through the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact, 66 million years ago, when its cephalopodan cousins, the beautiful and extinct group of swimming animals known as ammonites, did not. The shallow-water ammonites, living in and feeding on plankton, were either killed directly or starved to death in a charnel house that the shallow ocean depths had suddenly become. Far below the carnage, at about 1,000 feet, the nautiloids continued a life in the slow lane, rarely feeding, floating through life without the actions and metabolic costs of actively swimming organisms, such as squid and fish. They grow slowly but unlike other cephalopods, do not die after breeding. Some living nautilus might be a century old or older.

My trip to New Caledonia utterly changed my life. It brought me research papers, professorships, books, a marriage, and a son. It would send me on quests first to Europe and then into the Caucasus Mountains of Asia Minor to further understand the cause of the event that removed ammonites from Earth, yet spared the Nautilus. It sent me to South Africa to study an even more ancient extinction, then Australia, New Zealand, South America, and Antarctica. It was more adventure than ever imaginable by that 5-year-old boy in 1955, staring wide-eyed at the giant squid being fought to a draw in the climactic scene in Disney’s astonishing movie.

Chance, though, is not just the purveyor of gifts. After Mike’s death in 1984, I quit studying the nautilus. In fact, I quit science altogether. In the pit of my depression, fortune intervened in the person of Stephen Jay Gould. From his perch at Harvard, Gould had taken an abiding interest in all of us younger paleontologists, but a particular interest in my research, which showed that the ammonites disappeared suddenly after the cataclysmic asteroid, in contrast to the prior view that they went extinct gradually. Gould encouraged me to keep researching, beyond the ammonites. He helped me switch to the study of death writ large.

With Gould’s advice, I went deeper into the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, surely life’s worst day on Earth, when the world’s global forest burned to the ground, absolute darkness from dust clouds encircled the earth for six months, acid rain burned the shells off of calcareous plankton, and a monster tsunami picked up all of the dinosaurs on the vast, Cretaceous coastal plains, drowned them, and then hurled their carcasses against whatever high elevations finally subsided the monster waves.

In his novel The First Circle, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn noted that there were more paleontologists in the USSR during the grimmest period of the Stalin regime than any other kind of scientist. He told his readers why. Of all the sciences, paleontology allows its practitioners to abandon a hideous present to live in a more fascinating past. When I first read this, as a grad student, I didn’t understand it. After Mike, I did. For more than 20 years I lived in the deep past, writing books, trying to come to grips with Mike’s death.

My quest ultimately circled back to the present. In 2010, scientists in the United States government asked me to go back to the Pacific to study the nautilus, now being killed off by indigenous fishermen trying to feed their families in the southern Philippines.

I helped stop the harvesting of killer whales when I was young. Now I will finish my life trying to ensure that the longest living animal remains just that—living.

During my absence of 15 years, others, notably Bruce Saunders, of Bryn Mawr College; Neil Landman, of the American Museum of Natural History; and Andy Dunstan, of the University of Queensland, continued research into nautilus. They discovered, through DNA analysis of the living nautilus, more species than the four that were known during my decades in the Pacific. What had been called Nautilus pompilius in Indonesia, Palau, Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa, both sides of New Guinea, the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, the long barren coast of Western Australia, and most recently in Thailand, was found to consist of many distinct species. The term “living fossil,” which suggested a species with a low diversity, had to be overturned.

The research added a new chapter to the story of the nautilus. It revealed that the nautilus had dispersed longer distances than scientists had ever known, to establish safe harbors, and had evolved into smaller sizes to capitalize on scarce resources. Most of all, the new research showed that an ancient group wasn’t flickering out but had radiated into magnificent new species.

In 2011 and 2012 I returned to my old study sites in the Pacific, and collected DNA samples that helped confirm that Nautilus pompilius is many separate species. But I also discovered that unlike in the deep past, perhaps only a few thousand individuals make up each species. A few thousand individuals swimming long distances to be caught in a baited trap, from which they are hauled to the surface, killed, and sold for $1 a shell. For buttons and cheap tourist jewelry.

It’s a savage irony. Although the nautilus ruled the oceans for hundreds of millions of years, Earth’s changing conditions dwindled the number of species, about 3 million years ago, to less than a handful—or even a single species. Then came the advent of the Ice Ages and a radical drop in global sea level and temperatures, which, combined, created cool, highly oxygenated oceanic conditions similar to those when hundreds of nautiloid species existed. The nautilus was making a huge comeback in diversity, to the point where it may have been poised to once again be a presence in every ocean, rather than its current confinement to the western tropical Pacific.

But as recently as 50 years ago, the comeback hit a roadblock: us. In the Philippines and Indonesia, the distant nautilus species are being harvested to extinction. Between 2007 and 2010, the United States Department of Fish and Wildlife discovered that more than half a million nautilus shells or artifacts were imported into the United States alone. Fleets of nautilus boats now scour the coastlines of the South China Sea.

The life of the nautilus is providing its last lesson about chance events. But this time it’s about bad luck. It’s bad luck that nautiluses use their olfactory system rather than vision to find prey, because this trait makes them ludicrously easy to catch. Worse luck comes from a trait over which they never had control: they produce a shell with a visual power that humans covet—a covetousness, I can never forget, that contributed to Mike’s death.

This is not a death I can escape from, nor want to. I continue to travel to the Pacific islands to compile data to raise awareness about just how rare the nautilus has become. My work has been partly supported by two remarkable young fundraisers, Josiah Utsch, and Ridgely Kelly, of Maine, who launched a Web site, Save the Nautilus, after reading a 2011 article, “Loving the Chambered Nautilus to Death,” by science journalist William Broad, in The New York Times. They collect money, usually $1 at a time, from school kids, and so far have raised over $10,000.

In 2014 I traveled to the places in the Philippines and Vanuatu where I did my nautilus research in the ’80s. So much has changed. Far more industry, far more pollution, far more people. And far fewer nautiluses. Using underwater cameras for documentary evidence, we could for the first time make rather accurate population estimates. One population of nautiluses in the Philippines, a dwarf species isolated on a small island named Siquijor, is now extinct. Fished to extinction. All other populations are near that point. Many bear numerous shell breaks and scars from failed attacks by their human predators. The biggest irony and biggest sadness concerns the Allonautilus, the genus that my colleague Saunders and I named in 1997. Because of its rarity, the Allonautilus has become that much more collectible. Now a single shell of my genus can fetch up to $500, a fortune to the people in the remote region of Papua New Guinea where it lives.

Not a day goes by that I do not relish the luck of my own wonderful life. Nor does a day go by that I do not rue the chances that cost a young man his life. I helped stop the harvesting of killer whales when I was young, strong, and immortal. Now I will finish my life trying to ensure that the longest living animal known to science remains just that—living. Because this time if the nautilus survives, it will not be from chance.

Peter Ward is a professor of Biology and Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington. He is the author of In Search of Nautilus and, most recently, The Flooded Earth: Our Future in a World Without Ice Caps. He is beloved by his family, students, and dog.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in our “The Story of Nautilus” issue in April, 2013, under the title “Ingenious: Nautilus and Me.”