From our perspective here on Earth, constellations appear to be fixed groups of stars, immobile on the sky. But what if we could change that perspective?

In reality, it’d be close to impossible. We would have to travel tens to hundreds of light-years away from Earth for any change in the constellations to even begin to be noticeable. As of this moment, the farthest we (or any object we’ve made) have traveled is less than one five-hundreth of a light-year.

Just for fun, let’s say we could. What would our familiar patterns look like then? The stars that comprise them are all at different distances from us, traveling around the galaxy at different speeds, and living vastly different lives. Very few of them are even gravitationally bound to each other. Viewed from the side, they break apart into unrecognizable landscapes, their stories of gods and goddesses, ploughs and ladles, exposed as pure human fantasy. We are reminded that we live in a very big place.

Orion

Most commonly drawn as a hunter, the central stars that make up Orion have been interpreted in different ways over human history. They have often been taken to be a male figure. In Babylonia, he was “the true Sheppard of Anu.” In ancient Egypt, he was first the god “Osiris” and later the pharaoh “Unas.” Hungarian folklore portrayed Orion as either an archer or a reaper, while Muslims knew him as al-jabbar “the giant.” In India, the dots were connected to depict “Mriga, the deer,” and the Lakota Indians of North America drew a bison.

The most well known pattern, and story, of Orion comes from the Greeks. The son of Poseidon (god of the sea) and Euryale (a gorgon, and sister to Medusa), Orion was a giant with supernatural strength and excellent hunting skills. In an arrogant boast, he threatened to kill every living creature on Earth. Gaia (the goddess of the Earth and all animals) got word of this and sent a scorpion to kill him. Both Orion and the scorpion were cast into opposite ends of the sky, one rising while the other sets, forever reenacting the myth.

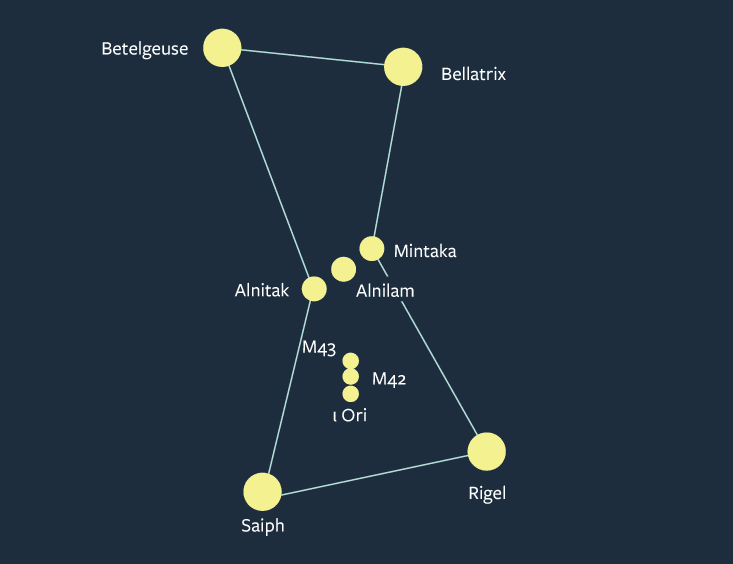

Even if you aren’t familiar with the mythology, odds are you’re aware of Orion and have seen it hanging over your head on some winter night. It is officially comprised of over 200 stars, but it takes only 10 points of light (eight stars and two nebulae) to outline the shape that most people associate with it—a shape that is still visible through light pollution in most cities. Betelgeuse and Bellatrix mark Orion’s shoulders; Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka his belt; Saiph and Rigel his knees or feet; M43, M42, and ι Ori his sword.

Looking at Orion takes you over 1,000 light-years out into space and over 1,000 years back in time (one light-year is the distance light travels in one year). The closest star to us in the simplified version of Orion is Bellatrix, at about 243 light-years; the farthest is Alnilam at about 1,342 light-years. The top two points of Orion’s sword, M43 and M42, are at about 1,600 and about 1,344 light-years, respectively. This means the light reaching your eyes from each of these points is not all the same age. The light from Bellatrix left the star when Captain Cook was commanding the first expedition of the HMS Endeavor. The light from Alnilam and M42 (aka the Orion Nebula) departed its sources around the time the Arabs embarked on their first siege of Constantinople. And the light from M43 (also known as De Mairan’s Nebula) left its birthplace a few years after the Visigoths sacked Rome in 410. With one upward glance at the night sky, you’re essentially seeing all that history.

Big Dipper

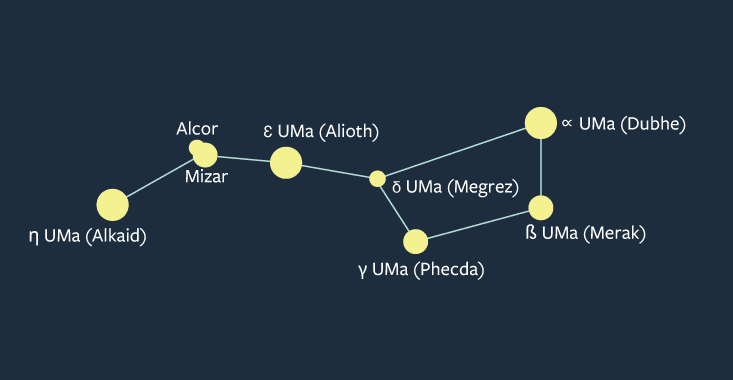

The Big Dipper is not a full constellation, but an asterism—a smaller recognizable grouping of stars. The seven points of light that outline the dipper comprise the brightest stars in the constellation Ursa Major (or Great Bear), the third largest constellation in the sky. While this asterism is recognized by many cultures, there are a surprising number of different interpretations of its shape.

In northern Europe it is most often depicted as a plough or wagon, while in India it represents the “Seven Great Sages.” In Mongolia, they are the “Seven Gods.” Here in North America we see the stars in the shape of a dipper, or ladle, but also as the back of the great bear in the full constellation.

While the stars of the Big Dipper are not as spread out in distance from Earth as those in Orion (they span less than 50 light-years in depth), the story of their discovery is a fascinating one. The middle “star” in the handle of the dipper is actually two separate points of light that are conflated together for anyone viewing them through a fair amount of light pollution. But get yourself a telescope or get outside of the city and you will actually see two points of light, called Mizar and Alcor.

Sometimes referred to as the “Horse and Rider,” it is said that the ability to distinguish these two stars was used as a vision test by the Roman Army. In the early 1600s with the advent of the telescope, Benedetto Castelli, a friend of Galileo Galilei, discovered that Mizar itself was two stars in a binary system, Mizar A and Mizar B, orbiting each other on time scales of thousands of years. Two centuries later, spectroscopic observations showed Mizar A was a binary too. Twenty years after that, spectroscopic observations of Mizar B showed it to be yet another binary, bringing the total number of stars in the Mizar-Alcor system to five. Nearly a century after that, in 2009, two separate teams of astronomers announced that Alcor was really Alcor A and Alcor B, also a binary system, bringing the count up to six.

The next time you look up at the Big Dipper, reflect on the dance taking place in that one fuzzy point of light: nested pairs of stars circling around each other, the two stars of Mizar A once around each other every 20 days or so, the two stars of Mizar B every six months, Mizar A and Mizar B once every 5,000 years, and Alcor A and B every century while simultaneously making a 750,000 year trek around the Mizar binary.

Cassiopeia

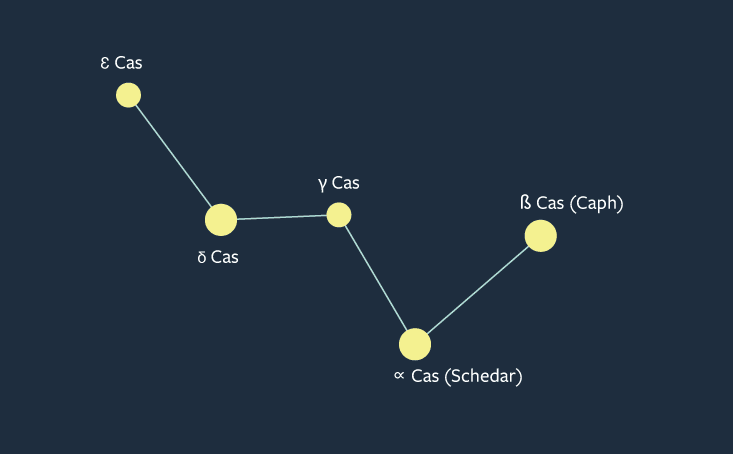

Cassiopeia is one of the constellations listed in the Almagest, Ptolemy’s second-century treatise on mathematics and astronomy. Drawing from Babylonian texts and the works of the Greek mathematician Hipparchus, Ptolemy identified a total of 48 constellations, all of which are still recognized today. In Ptolemy’s worldview, the stars sat on the surface of a fixed celestial sphere at some great distance that rotated around the Earth. Little did he imagine that the five brightest stars of Cassiopeia might actually be spread out over 550 light-years in distance from Earth. Or that the nearest (β Cas) might only be 54 light-years away.

The constellation is named after Cassiopeia, queen of Aethiopia (what we know today as Ethiopia). Married to Cepheus, king of Aethiopia, Cassiopeia had a quality common to most mythological figures: arrogance. She once boasted that her daughter, Andromeda, was more beautiful than Poseidon’s sea nymphs, the Nereids, and perhaps that even she herself was more beautiful. For that Poseidon sent the sea monster, Cetus, to attack Aethiopia. After consulting an oracle, Cassiopeia was told the only way to save her people was to sacrifice her only daughter as an offering to Cetus. As often happens in Greek mythology, a hero arrived just in time to save Andromeda. Perseus killed the monster Cetus, rescued Andromeda, and then married her. Lest Cassiopeia remain unpunished, Poseidon placed her in the sky tied to her throne. Since Cassiopeia is at such a high celestial latitude, the constellation can be seen year-round revolving around the sky, always facing towards the North Star. Thus for half of every night, the queen hangs upside down as punishment for her vanity.

β Cas (aka Caph) is currently in the process of turning into a red giant. Three times the size of the sun and almost 30 times brighter, it currently rotates about its axis once a day. For comparison, our sun takes over 26 days to make one complete rotation. β Cas is spinning so fast, it’s actually bulging out at its equator, making it 24 percent fatter than it would be if it were spinning normally.

γ Cas is the farthest of the five stars making up Cassiopeia, at more than 600 light-years away. It’s what is known as a variable star: a star that varies in brightness with some regularity. γCas is actually the namesake for a particular class of variable stars known as Gamma Cassiopeiae variables. At times it can outshine two of its brighter companions, α Cas and β Cas, and at 19 times more massive and five times as hot, it gives off 55,000 times more energy than our sun.

In addition to γ Cas, α Cas and β Cas are also known to be variable stars, both of different classes. δ Cas varies in brightness as well, but for a different reason—it is an eclipsing binary, meaning it’s two stars instead of one and the plane they orbit each other in is actually edge-on as seen from Earth. So when δ Cas appears brighter, both stars are visible and when δ Cas dims, one star is eclipsing the other.

So if Cassiopeia ever looks a little brighter or a little dimmer, night to night or month to month, now you know why. Those fixed, unmoving, and unchanging stars of Ptolemy are really anything but.

Summer Ash is the Director of Outreach for Columbia University’s Department of Astronomy. She is also the “In-House Astrophysicist” for The Rachel Maddow Show and tweets as @Summer_Ash.