This year marks three decades since 1984, the titular year of George Orwell’s classic novel. Among the many articles and events marking this anniversary, I was fortunate to participate in one—a panel discussion. It was unusual in a couple of ways.

For one thing, it took place among the concert stages and art-filled forests of England’s Latitude Festival. Later in the day, our pavilion was taken over by a rap artist in a feather boa. Rain-soaked revelers in headdresses tripped across the fields outside.

Also unusual was that the panel members were scientists and engineers, not historians or politicians. Wasn’t the book really a social commentary, and not a technical one? In re-reading it, I discovered that it was both. In Orwell’s dystopia, the ruling class squanders the unprecedented productivity of technology on endless war, to avoid ceding wealth and power to the lower class. They also construct a (vaguely familiar) surveillance state enabled by a diffuse and deeply embedded communications technology.

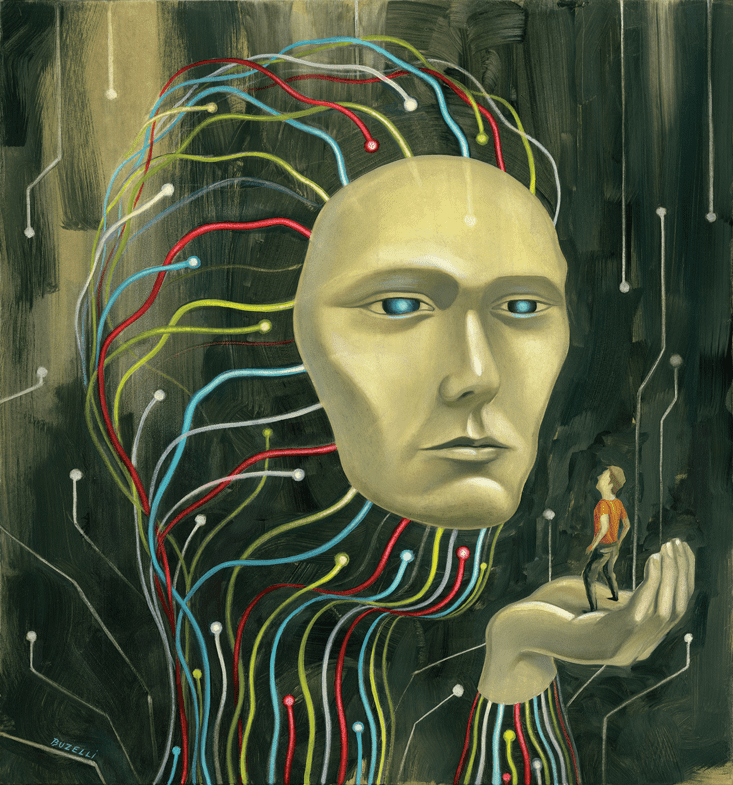

In technology as in culture, Orwell suggests that we are caught in the long, inevitable sweep of history. Are we in control of our technology, he asks, or is it in control of us? This question sits squarely in the Nautilus wheelhouse. How could it not? It is, after all, the subject of our fall Quarterly cover story.

Science writer Lee Billings tells us how, while attending a series of brashly optimistic conferences on the Singularity (our radical and imminent transformation through technology), he discovered a more nuanced, humanist, and rational view of the future in the writings of another mid-20th-century thinker: the Polish futurist and science fiction author, Stanislaw Lem. It is too early to celebrate our technological ascension, Lem says, since we will carry our very human strengths and weaknesses with us into the future. Paradoxically, Lem argues, we will be able control our fate only if we cede some of our agency to machines.

Like Orwell, Lem challenges us to think deeply about how we are changing ourselves, consciously or otherwise, and reminds us that, in the broadest view, questions of technology, science, and society become indivisible. And there’s nothing more Nautilus than that.

Welcome to the Fall 2014 Nautilus Quarterly.