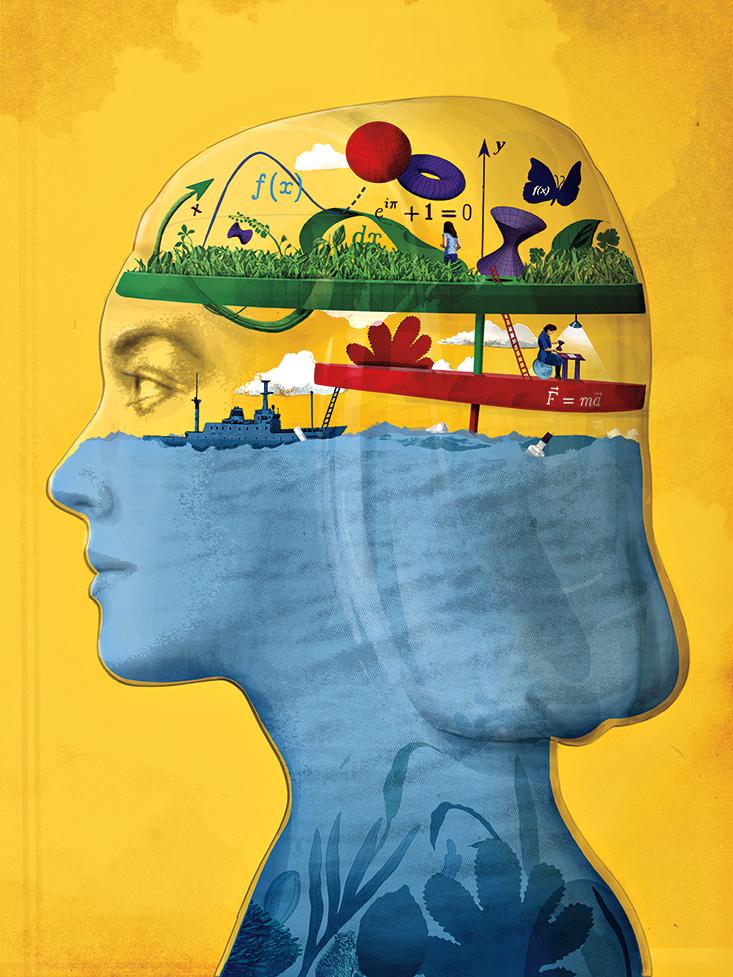

I was a wayward kid who grew up on the literary side of life, treating math and science as if they were pustules from the plague. So it’s a little strange how I’ve ended up now—someone who dances daily with triple integrals, Fourier transforms, and that crown jewel of mathematics, Euler’s equation. It’s hard to believe I’ve flipped from a virtually congenital math-phobe to a professor of engineering.

One day, one of my students asked me how I did it—how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer Hell—with lots of difficulty! After all, I’d flunked my way through elementary, middle, and high school math and science. In fact, I didn’t start studying remedial math until I left the Army at age 26. If there were a textbook example of the potential for adult neural plasticity, I’d be Exhibit A.

Learning math and then science as an adult gave me passage into the empowering world of engineering. But these hard-won, adult-age changes in my brain have also given me an insider’s perspective on the neuroplasticity that underlies adult learning. Fortunately, my doctoral training in systems engineering—tying together the big picture of different STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) disciplines—and then my later research and writing focusing on how humans think have helped me make sense of recent advances in neuroscience and cognitive psychology related to learning.

In the years since I received my doctorate, thousands of students have swept through my classrooms—students who have been reared in elementary school and high school to believe that understanding math through active discussion is the talisman of learning. If you can explain what you’ve learned to others, perhaps drawing them a picture, the thinking goes, you must

understand it.

Japan has become seen as a much-admired and emulated exemplar of these active, “understanding-centered” teaching methods. But what’s often missing from the discussion is the rest of the story: Japan is also home of the Kumon method of teaching mathematics, which emphasizes memorization, repetition, and rote learning hand-in-hand with developing the child’s mastery over the material. This intense afterschool program, and others like it, is embraced by millions of parents in Japan and around the world who supplement their child’s participatory education with plenty of practice, repetition, and yes, intelligently designed rote learning, to allow them to gain hard-won fluency with the material.

Teachers can inadvertently set their students up for failure as those students blunder in illusions of competence.

In the United States, the emphasis on understanding sometimes seems to have replaced rather than complemented older teaching methods that scientists are—and have been—telling us work with the brain’s natural process to learn complex subjects like math and science.

The latest wave in educational reform in mathematics involves the Common Core—an attempt to set strong, uniform standards across the U.S., although critics are weighing in to say the standards fail by comparison with high-achieving countries. At least superficially, the standards seem to show a sensible perspective. They propose that in mathematics, students should gain equal facility in conceptual understanding, procedural skills and fluency, and application.

The devil, of course, lies in the details of implementation. In the current educational climate, memorization and repetition in the STEM disciplines (as opposed to in the study of language or music), are often seen as demeaning and a waste of time for students and teachers alike. Many teachers have long been taught that conceptual understanding in STEM trumps everything else. And indeed, it’s easier for teachers to induce students to discuss a mathematical subject (which, if done properly, can do much to help promote understanding) than it is for that teacher to tediously grade math homework. What this all means is that, despite the fact that procedural skills and fluency, along with application, are supposed to be given equal emphasis with conceptual understanding, all too often it doesn’t happen. Imparting a conceptual understanding reigns supreme—especially during precious class time.

The problem with focusing relentlessly on understanding is that math and science students can often grasp essentials of an important idea, but this understanding can quickly slip away without consolidation through practice and repetition. Worse, students often believe they understand something when, in fact, they don’t. By championing the importance of understanding, teachers can inadvertently set their students up for failure as those students blunder in illusions of competence. As one (failing) engineering student recently told me: “I just don’t see how I could have done so poorly. I understood it when you taught it in class.” My student may have thought he’d understood it at the time, and perhaps he did, but he’d never practiced using the concept to truly internalize it. He had not developed any kind of procedural fluency or ability to apply what he thought he understood.

There is an interesting connection between learning math and science, and learning a sport. When you learn how to swing a golf club, you perfect that swing from lots of repetition over a period of years. Your body knows what to do from a single thought—one chunk—instead of having to recall all the complex steps involved in hitting a ball.

In the same way, once you understand why you do something in math and science, you don’t have to keep re-explaining the how to yourself every time you do it. It’s not necessary to go around with 25 marbles in your pocket and lay out 5 rows of 5 marbles again and again so that you get that 5 x 5 = 25. At some point, you just know it fluently from memory. You memorize the idea that you simply add exponents—those little superscript numbers—when multiplying numbers that have the same base (104 x 105 = 109). If you use the procedure a lot, by doing many different types of problems, you will find that you understand both the why and the how behind the procedure very well indeed. The greater understanding results from the fact that your mind constructed the patterns of meaning. Continually focusing on understanding itself actually gets in the way.

I learned these things about math and the process of learning not in the K-12 classroom but in the course of my life, as a kid who grew up reading Madeleine L’Engle and Dostoyevsky, who went on to study language at one of the world’s leading language institutes, and then to make the dramatic shift to become a professor of engineering.

As a young woman with a yen for learning language and no money or skills to speak of, I couldn’t afford to go to college (college loans weren’t then in the picture). So I launched directly from high school into the Army. I had loved learning new languages in high school, and the Army seemed to be a place where people could actually get paid for their language study, even as they attended the top-ranked Defense Language Institute—a place that had made language- learning a science. I chose Russian because it was very different from English, but not so difficult that I could study it for a lifetime only to perhaps gain the fluency of a 4-year-old. Besides, the Iron Curtain was mysteriously appealing—could I somehow use my knowledge of Russian to peer behind it?

After leaving the service, I became a translator for the Russians on Soviet trawlers on the Bering Sea. Working for the Russians was fun and engrossing—but it was also a superficially glamorous form of migrant work. You go to sea during fishing season, make a decent salary while getting drunk all the time, then go back to port when the season’s over and hope they’ll rehire you next year. There was pretty much only one other alternative for a Russian language speaker—working for the National Security Agency. (My Army contacts kept pointing me that way, but it wasn’t for me.)

I began to realize that while knowing another language was nice, it was also a skill with limited opportunities and potential. People weren’t pounding down my door looking for my Russian declension abilities. Unless, that is, I was willing to put up with seasickness and sporadic malnutrition out on stinking trawlers in the middle of the Bering Sea. I couldn’t help but reflect back on the West Point-trained engineers I’d worked with in the Army. Their mathematically and scientifically based approach to problem-solving was clearly useful for the real world—far more useful than my youthful misadventures with math had been able to imagine.

So, at age 26, as I was leaving the Army and casting about for fresh opportunities, it occurred to me: If I really wanted to try something new, why not tackle something that could open a whole world of new perspectives for me? Something like engineering? That meant I would be trying to learn another very different language—the language of calculus.

You go to sea during fishing season, make a decent salary while getting drunk all the time, then go back to port when the season’s over.

With my poor understanding of even the simplest math, my post-Army retraining efforts began with not-for-credit remedial algebra and trigonometry. This was way below mathematical ground zero for most college students. Trying to reprogram my brain sometimes seemed like a ridiculous idea—especially when I looked at the fresh young faces of my younger classmates and realized that many of them had already dropped their hard math and science classes—and here I was heading right for them. But in my case, from my experience becoming fluent in Russian as an adult, I suspected—or maybe I just hoped—that there might be aspects to language learning that I might apply to learning in math and science.

What I had done in learning Russian was to emphasize not just understanding of the language, but fluency. Fluency of something whole like a language requires a kind of familiarity that only repeated and varied interaction with the parts can develop. Where my language classmates had often been content to concentrate on simply understanding Russian they heard or read, I instead tried to gain an internalized, deep-rooted fluency with the words and language structure. I wouldn’t just be satisfied to know that понимать meant “to understand.” I’d practice with the verb—putting it through its paces by conjugating it repeatedly with all sorts of tenses, and then moving on to putting it into sentences, and then finally to understanding not only when to use this form of the verb, but also when not to use it. I practiced recalling all these aspects and variations quickly. After all, through practice, you can understand and translate dozens—even thousands— of words in another language. But if you aren’t fluent, when someone throws a bunch of words at you quickly, as with normal speaking (which always sounds horrifically fast when you’re learning a new language), you have no idea what they’re actually saying, even though technically you understand all the component words and structure. And you certainly can’t speak quickly enough yourself for native speakers to find it enjoyable to listen to you.

This approach—which focused on fluency instead of simple understanding—put me at the top of the class. And I didn’t realize it then, but this approach to learning language had given me an intuitive understanding of a fundamental core of learning and the development of expertise—chunking.

Chunking was originally conceptualized in the groundbreaking work of Herbert Simon in his analysis of chess—chunks were envisioned as the varying neural counterparts of different chess patterns. Gradually, neuroscientists came to realize that experts such as chess grand masters are experts because they have stored thousands of chunks of knowledge about their area of expertise in their long-term memory. Chess masters, for example, can recall tens of thousands of different chess patterns. Whatever the discipline, experts can call up to consciousness one or several of these well-knit-together, chunked neural subroutines to analyze and react to a new learning situation. This level of true understanding, and ability to use that understanding in new situations, comes only with the kind of rigor and familiarity that repetition, memorization, and practice can foster.

As studies of chess masters, emergency room physicians, and fighter pilots have shown, in times of critical stress, conscious analysis of a situation is replaced by quick, subconscious processing as these experts rapidly draw on their deeply ingrained repertoire of neural subroutines—chunks. At some point, self-consciously “understanding” why you do what you do just slows you down and interrupts flow, resulting in worse decisions. When I felt intuitively that there might be a connection between learning a new language and learning mathematics, I was right. Day-by-day, sustained practice of Russian fired and wired together my neural circuits, and I gradually began to knit together chunks of Slavic insight that I could call into working memory with ease. By interleaving my learning—in other words, practicing so that I knew not only when to use that word, but when not to use it, or to use a different variant of it—I was actually using the same approaches that expert practitioners use to learn in math and science.

When learning math and engineering as an adult, I began by using the same strategy I’d used to learn language. I’d look at an equation, to take a very simple example, Newton’s second law of f = ma. I practiced feeling what each of the letters meant—f for force was a push, m for mass was a kind of weighty resistance to my push, and a was the exhilarating feeling of acceleration. (The equivalent in Russian was learning to physically sound out the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet.) I memorized the equation so I could carry it around with me in my head and play with it. If m and a were big numbers, what did that do to f when I pushed it through the equation? If f was big and a was small, what did that do to m? How did the units match on each side? Playing with the equation was like conjugating a verb. I was beginning to intuit that the sparse outlines of the equation were like a metaphorical poem, with all sorts of beautiful symbolic representations embedded within it. Although I wouldn’t have put it that way at the time, the truth was that to learn math and science well, I had to slowly, day by day, build solid neural “chunked” subroutines—such as surrounding the simple equation f = ma—that I could easily call to mind from long term memory, much as I’d done with Russian.

Time after time, professors in mathematics and the sciences have told me that building well-ingrained chunks of expertise through practice and repetition was absolutely vital to their success. Understanding doesn’t build fluency; instead, fluency builds understanding. In fact, I believe that true understanding of a complex subject comes only from fluency.

In other words, in science and math education in particular, it’s easy to slip into teaching methods that emphasize understanding and that avoid the sometimes painful repetition and practice that underlie fluency. I learned Russian not just by understanding it—understanding, after all, is facile, and can easily slip away. (What did that word понимать mean?) I learned Russian by gaining fluency through practice, repetition, and rote learning—but rote learning that emphasized the ability to think flexibly and quickly. I learned math and science by applying precisely those same ideas. Language, math, and science, as with almost all areas of human expertise, draw on the same reservoir of brain mechanisms.

As I forayed into a new life, becoming an electrical engineer and, eventually, a professor of engineering, I left the Russian language behind. But 25 years after I’d last raised an inebriated glass on the Soviet trawlers, my family and I decided to take the trans-Siberian railway across Russia. Although I was excited to take the long-dreamed-of trip, I was also worried. I’d barely uttered a word of Russian in all that time. What if I’d lost it all? What had those years of gaining fluency really bought me?

Sure enough, when we first got on the train, I spoke Russian like a 2-year-old. I’d grasp for words, my declensions and conjugations were all wrong, and my formerly near-perfect accent sounded dreadful. But the foundation was there, and day by day, my Russian improved. And even with my rudimentary Russian, I could handle the day-to-day needs of our traveling. Soon, tour guides were coming to me for help translating for the other passengers. When we finally arrived in Moscow, we hopped in a taxi. The driver, I soon discovered, was intent on ripping us off—heading directly the wrong way and trapping us in a logjam of cars, where he expected us ignorant foreigners to quietly acquiesce to an unnecessary extra hour of meter time. Suddenly, Russian words I hadn’t spoken for decades flew from my mouth. I hadn’t even consciously known I knew those words.

Underneath it all, when it was needed, the fluency was there—and it quickly got us out of trouble (and into another taxi). Fluency allows understanding to become embedded, emerging when needed.

As I look today at the shortage of science and math majors in this country, and our current trend in how we teach people to learn, and as I reflect on my own pathway, knowing what I know now about the brain, it occurs to me that we can do better. As parents and teachers, we can use simple, accessible methods for deepening understanding and making it useful and flexible. We can encourage others and ourselves to try new disciplines that we thought were too hard—math, dance, physics, language, chemistry, music—opening new worlds for ourselves and others.

As I discovered, having a basic, deep-seated fluency in math and science—not just an “understanding,” is critical. It opens doors for many of life’s most intriguing jobs. Looking back, I realize that I didn’t have to just blindly follow my initial inclinations and passions. The “fluency” part of me that loved literature and language was also the same part of me that ultimately fell in love with math and science—and transformed and enriched my life.

This article appears in the Fall 2014 Nautilus Quarterly. Subscribe today!

Barbara Oakley is a professor of engineering at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, and the author of, most recently, A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). She is also co-instructor, with Terrence Sejnowski, the Francis Crick Professor at the Salk Institute, of one of the world’s largest online courses, “Learning How to Learn,” with Coursera.