Ruth and Harold “Doc” Knapke met in elementary school. They exchanged letters during the war, when Doc was stationed in Germany. After he returned their romance began in earnest. They married, raised six children and celebrated 65 anniversaries together. And then on a single day in August 2013, in the room they shared in an Ohio nursing home, they died.

“No relationship was ever perfect, but theirs was one of the better relationships I ever observed,” says their daughter Margaret Knapke, 61, a somatic therapist. “They were always like Velcro. They couldn’t stand to be separated.”

For years, Knapke says, she and her siblings watched their father’s health crumble. He suffered from longstanding heart problems and had begun showing signs of dementia. He lost interest in things he once enjoyed, and dozed nearly all the time. “We asked each other, why do you suppose he’s still here? The only thing we could come up with was that he was here for Mom,” she says. “He’d wake up from a long snooze and ask, ‘How’s your mother?’ ”

Then Ruth developed a rare infection. Lying unconscious in the nursing-home room she shared with Doc, it became clear she was in her final days. The Knapke children sat down to tell Doc that she wasn’t going to wake up again. “He didn’t go back to sleep. I could see he was processing it for hours,” says Margaret. He died the next morning, and Ruth followed that evening.

Knapke sees her parents’ same-day deaths as a conscious decision—two hearts shutting off together. “My feeling was that he was hanging around for her,” she says. Knapke believes her father wanted to show her mother the way to the next realm. “He knew she needed something else from him, so he switched gears and let go,” she says. “I feel he chose to go first so he could help her. It was definitely an act of love on his part.”

Deadly grief is not about stress alone, scientists say. It shines a light on the physiological bonds of love.

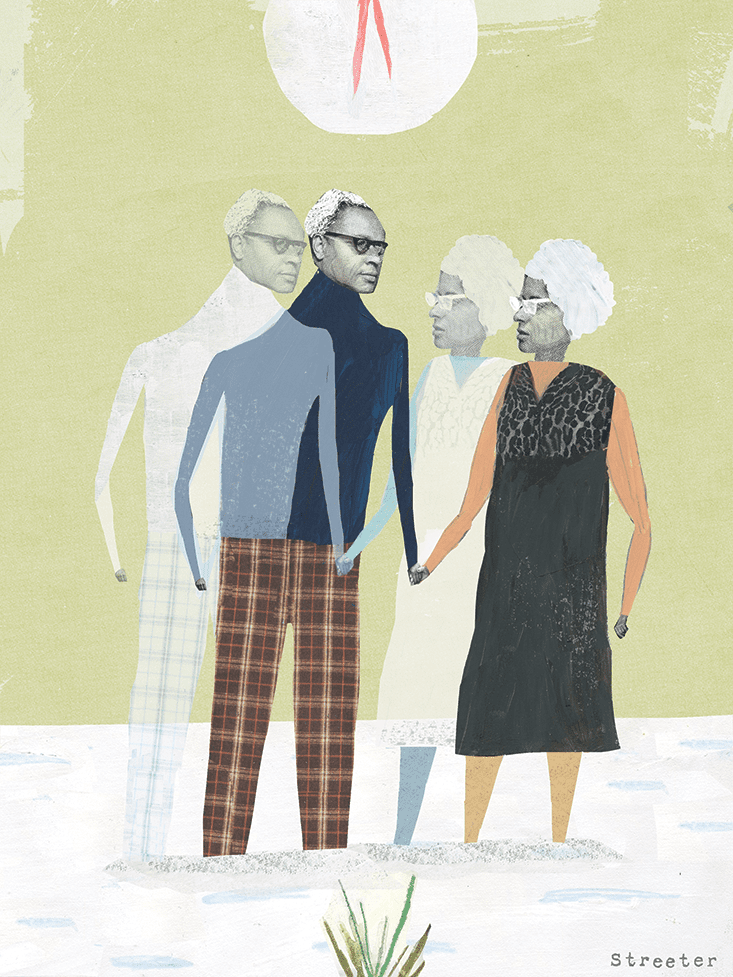

The Knapkes’ story may be special, but it’s not unique. Every few months, some small-town paper publishes a similar human-interest story. Last July, People magazine ran the story of 94-year-old California residents Helen and Les Brown, who were married for 75 years. They’d been born on the same day and died just one day apart. In February, a photo of New York residents Ed Hale, 83, and his wife Floreen, 82, made the rounds on social media. The image showed the couple holding hands through the railings of their side-by-side hospital beds. They died mere hours apart.

Death by heartbreak is a literary staple; even Shakespeare wrote of “deadly grief.” The emotional devastation of losing a loved one can certainly feel like physical pain. But can you really die from a broken heart? As it turns out, you can, from “broken-heart syndrome,” also known as stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Studies of bereavement, in fact, provide another harsh indictment of the effects of stress on human health. But deadly grief is not about stress alone, scientists say. It shines a light on the physiological bonds of love, ceded to us by evolution, so often best understood when broken.

Studies from around the world have confirmed that people have an increased risk of dying in the weeks and months after their spouses pass away. In 2011, researchers from Harvard University and the University of Yamanashi, Tokyo pooled the results of 15 different studies, with data on more than 2.2 million people. They estimated a 41 percent increase in the risk of death in the first six months after losing a spouse. The effect didn’t just apply to the elderly. People under 65 were as likely to die in the months following a spouse’s death as those over 65. The magnitude of the “widowhood effect” was much stronger for men than it was for women.

The explanation for the gender difference may be simple logistics. Particularly in previous generations, women did more of the work caring for their husbands and households. They kept in touch with adult children and were in charge of the family social life, says Tracy Schroepfer, a professor of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who studies the psychosocial needs of terminally ill elders and their families. When their wives died, men were more likely to become isolated. “Loneliness was really great, and for men who couldn’t shop and cook for themselves, it could impact their nutrition and health,” she says.

While women might be more resilient to losing a spouse, however, they aren’t immune to the deadly effects of grief. A 2013 study of more than 69,000 women in the United States found that a mother’s risk of dying increased 133 percent in the two years following the death of a child.

The idea that grief can increase the risk of dying makes intuitive sense, especially among those who spend time with the ill, says Roy Ziegelstein, a cardiologist and vice dean of education at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “I think that if you polled doctors, they’d overwhelmingly tell you it happens not infrequently.”

Yvonne Matienko, a nurse and holistic health coach from Pennsylvania, knows all about broken-heart syndrome. Matienko was 51, without any history of heart problems, when she received a shocking phone call. Her teenage granddaughter, with whom she lived, had been involved in a serious car crash. Matienko rushed to the scene. “When I saw the trauma people and helicopters and the kids laying on the highway, my heart started racing,” she says.

Later that night, relieved that her granddaughter would be okay, she poured a glass of wine and tried to relax. Suddenly, she was overcome by dizziness. Then she passed out. “That’s the last thing I remember,” she says. Matienko was rushed back to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with stress-induced cardiomyopathy.

Unlike a heart attack, broken-heart syndrome doesn’t stem from blocked arteries. It appears to be brought on by a sudden surge in stress hormones including epinephrine (more commonly known as adrenaline) and its chemical cousin norepinephrine. That rush of hormones is a normal, healthy response to extreme stress. It fuels the body’s famed “fight or flight” response that prepares you for dealing with major threats. But in some cases the sudden flood of hormones essentially shocks the heart, preventing it from pumping normally. On an X-ray or ultrasound, the heart’s left ventricle appears enlarged and misshapen. The unusual shape is said to resemble a Japanese octopus trap called a tako-tsubo, hence the syndrome’s other alias: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The syndrome doesn’t permanently damage the heart’s muscle tissue, and patients often make a full recovery. A year after her ordeal, Matienko has no lingering heart problems. Still, the condition can be deadly if the misshapen heart can’t pump enough blood to the rest of the body.

Grief can affect the heart in less immediate ways. British researchers recently analyzed data from more than 30,000 surviving spouses in a primary care database from the United Kingdom. According to the study, published in February in JAMA Internal Medicine, the risk of heart attack and stroke doubled during the first 30 days after a spouse’s death, then began to settle back to normal levels.

“We know that acute emotional stress can cause a variety of problems with the heart,” Ziegelstein says. Just as it does with physical strain, the heart demands more oxygen during times of emotional upheaval. When emotions run high, however, the blood vessels don’t dilate. Ziegelstein says emotional stress may actually cause the vessels to constrict. The result is that coronary blood flow is decreased. Your heart craves more oxygen but it gets less. That can lead to dangerously abnormal heart rhythms and even heart attacks, particularly in people who already have blocked arteries.

People nearing the end seem to be able to choose to live for another day to satisfy a loved one.

But the heart isn’t the only organ damaged by grief. Stressful events can also tax the immune system, explains James Coan, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Virginia. The body’s complex fight-or-flight reaction doesn’t come cheap. To launch the chemical cascade that allows you to outrun a bear or a burglar, the body has to borrow resources from other body systems. “One of the places your body can draw a lot of bioenergetic resources from is the immune system,” says Coan. “When you have chronic stress, you’re constantly degrading your ability to heal and fight off infection. That’s why chronic stress is associated with so many bad health outcomes.”

Other more subtle factors may influence how and why couples die so soon after one another. Schroepfer, of the University of Wisconsin, who has spent considerable time with people at the end of their lives, both in her current work and in her former career as a hospice social worker, says people nearing the end seem to be able to choose to live for another day to satisfy a loved one. “In working with people who are dying, I have seen them make those choices,” she says. “I think there is a lot we don’t understand about willpower.”

Schroepfer will never forget when one of her hospice patients was hovering at the edge of death. She was unconscious, barely hanging on. Her children had all told their mother it was okay to let go. But the woman’s grieving husband hadn’t been able to give his blessing. Finally, after talking with his daughter, he decided he was ready to give his wife permission to leave them. “He sat down beside her and told her he loved her, and that it was okay,” Schroepfer recalls. “He got up to walk back to his chair. Right after he sat down, she raised her head out of the coma, said ‘I love you,’ and died. I was glad their daughter was there too, or I would have thought I’d imagined it.”

Although medical researchers may not be able to pinpoint where that surge of willpower comes from, they have shown evidence for people’s remarkable ability to hold on and let go at will. David Phillips, a professor of sociology at the University of California, San Diego, who specializes in statistical analysis of sociological data, has looked at the link between mortality and culturally meaningful events. Just before Passover each year, he found, the death rate for Jewish people fell sharply below normal levels, and rose again immediately afterward. Non-Jewish people showed no change in mortality before or after the holiday. Similarly, he showed a drop in deaths among Chinese people before their symbolically important Harvest Moon Festival, and a corresponding rise after the event had ended. If people can will their bodies to hold out for one more Harvest Moon Festival, one more family reunion, then why not for love?

After all, love doesn’t just feel good, Coan has found, it is good for us: Happy relationships can protect against the negative effects of stress. In studies designed to measure how social support influences the stress response, Coan brings volunteers into an MRI scanner and threatens to zap them with an electric shock. Periodically a symbol flashes before their eyes, indicating there’s a 20 percent chance they’ll receive a shock in the next few seconds. The goal, he says, is to create an “anticipatory anxiety” that mimics the feeling you get from everyday stressors like a looming work deadline.

But the volunteers aren’t in it alone. Some are holding the hand of someone they trust—a romantic partner, parent, or close friend. Others are holding the hand of a stranger. Coan has found that brain activity in the hypothalamus, the region heavily implicated in the body’s stress response, differs between those holding a loved one’s hand and those holding hands with a stranger. Clasping hands with a loved one tamps down threat-related activity.

“The brain pathway of romantic love is next to the basic factories involved in thirst and hunger. It’s a survival system.”

In a related study, Coan set up volunteers in the scanner and asked them to hold a partner’s hand. But this time, the flashing symbol warned their partner was about to get the shock. Coan found that volunteers’ brain patterns were indistinguishable when the threat was directed at them or their partner. That wasn’t true when holding a stranger’s hand. “As far as your brain is concerned, a partner is not just metaphorically, but literally, a part of who you are,” he says.

When you lose a partner, you really do lose a part of yourself. You also lose a piece of your coping mechanism for dealing with life’s difficulties, Coan says. “You have to adjust your stress response. You’re going to be withdrawing resources from your immune-system, and your body is going to take a big hit.”

Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist at Rutgers University, author of Why We Love and other books about the evolution and chemistry of romantic attraction, explains that the physiological wounds of grief can underscore the power and importance of love. As social animals, Fisher says, we evolved to fall in love and form pair bonds with other members of our species. “The basic brain pathway of romantic love is way at the bottom of the brain, next to the basic factories involved in thirst and hunger. It’s a survival system.”

Fisher describes three distinct features of that system: one for feelings of attachment, another for feelings of intense romantic love, and a third for sex drive. Attachment centers around oxytocin, a hormone that plays a key role in pair bonding. “When you have a good marriage, you’re hugging, kissing, giving massages, listening to each other’s voices. All of those things drive up oxytocin,” she says. Aside from its role in social bonding, oxytocin reduces the stress hormone cortisol, she adds.

Romantic love triggers the brain’s system for dopamine, a chemical messenger that plays an important role in brain pathways for pleasure and rewards. “When you’re in love, dopamine is regularly activated. It gives you energy, focus, motivation, optimism, creativity—the kinds of things you need to live a healthy life,” Fisher says. Sex, too, activates the dopamine system, and orgasms send a flood of oxytocin into the bloodstream. Regular sex also activates the testosterone system in men, which can contribute to a sense of well-being, Fisher says.

Add them all up, and there’s a lot of potential for havoc in the brain after losing a romantic partner. In a widow, Fisher says, “All three of these brain systems are basically deactivated.” Combined with other changes that a widow experiences—changes to daily habits, social connections, expectations about the rest of his or her life—that chemical chaos can tip the scales toward an untimely end.

Kirsten Weir is a freelance science writer in Minneapolis.