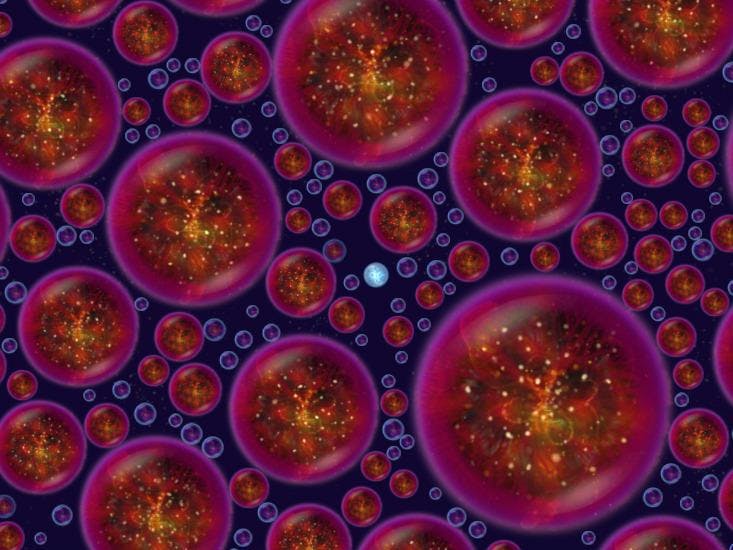

In an era when fashion demands thinness, the video game Osmos, in which the goal is attaining ever greater levels of corpulence, stands as a rare exception. You start the game as a tiny, spherical mote, trying to grow by absorbing even smaller motes, merging with them in order to grow larger and more powerful. But run into a larger body and you will be absorbed, your entity “terminated.” But power doesn’t come for free: The mote propels itself by ejecting part of its own body behind it, shooting away some of its mass in exchange for a push in the opposite direction. It’s a perfect example of Newton’s third law (“For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction”) and also makes for a key strategic point in the game: Every move has to be worth the expense.

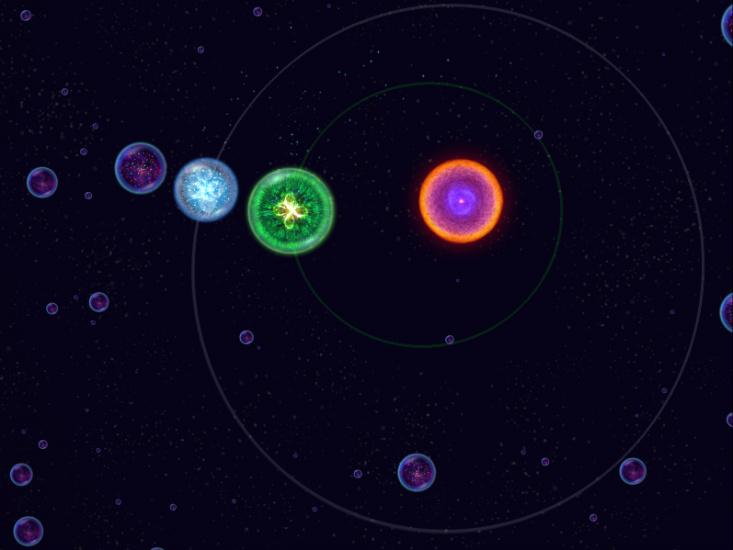

Osmos includes eight different types of worlds, each of which simulates the properties of a different imaginary but in some ways realistic physical system. The systems range from the microscopic domain of intelligent single-celled organisms to the galactic scale of planets in orbit around a star, and the player has to be prepared to change their game strategy to suit the different forces at work in the levels. By forcing people to really grapple with the laws of physics in this challenging way, the game can help them get a deeper understanding than they might get from conventional reading and problem-solving.

But just as important, the game is fun. It is massively popular on Android and iOS devices, with millions of purchases and tens of thousands of overwhelmingly positive user reviews. It also was named a game of the year by Apple and at least four tech publications in 2010.

Nautilus spoke to the game’s creator, Eddy Boxerman, about what makes Osmos work, how it connects cosmic and microscopic scales, and just what “ambient physics” actually means.

Where did the inspiration to make Osmos come from?

It was really based on the things that I had studied [in college and grad school]. I had taken a course on spacecraft dynamics, and my masters focused on computer modeling of deformable—squishy—3D substances. Specifically, it was designing system simulations that were trying to efficiently and realistically simulate textiles. And though that is a pretty esoteric subject, all that fooling about with the models gave me different thoughts on what might be fun to interact with in a digital world. These squishy objects behaved, in a way, like a lava lamp. And I think Osmos can be described as a sort of lava lamp, but on a solar-system level.

The first name of the game was Blob, which is pretty self-explanatory, and then I eventually came up with Osmos as a mix of “osmosis” and “cosmos.”

The game-play came first [the way the players interact with the game], and the then the visual style. Essentially it is a lot of circles, but we wanted an ambiguous mix of microscopic and galactic levels. It is an ambiguous mix, but in terms of the physics at the heart of the game, the physics can apply at any scale.

What is the relationship between the microbial and the cosmic scale in Osmos?

A lot of the reason why there is a connection between the microscopic and the cosmic in Osmos is because of the physics—it just so happens that there is a way to apply it to both. If you are thinking of a microbe trying to navigate and ingest food to sustain itself versus a spaceship needing to gather fuel in order to continue on its journey, there is a parallel there even if the sizes and the mediums are different. The physics involved are straight out of Newton, and they apply at both the microscopic and the cosmic level.

The difference I think lies in the nature of intelligence. There is nothing in outer space that behaves in an intelligent way, but on the microscopic level there is. The AI programming really came in with the microbial levels. I started watching videos of microbes and the way they move and behave, so when I was working on the AI I definitely took that into account, and I took inspiration from how they look. You can tell from the style of the art, which I designed alongside Kun Chang, our art director, that it is definitely influenced by a few different types of bacteria.

Do you think that there is something intuitive about this kind of physics that comes through in the experience of it?

Young children, like my nephew at the age of 5, can play Osmos. These children haven’t learnt these theories but they understand a part of the way the world works by their experience of it, and the game formalizes this intuitive knowledge and gives people who either don’t know, or people who are learning about these difficult theories—or even people who know all about them—a kind of intuition about how these systems work in reality by letting them experience being a part of the system, instead of just reading it on a page.

The course I took in spacecraft dynamics, I remember working about the orbital mechanics of planets and that stuff was tricky to learn. Until I added those orbit systems to Osmos years later I didn’t have the same intuitive feel of how to move and navigate in a system like that. There are various ways that systems like that can behave, and you get a feel for them after a while [playing the game].

The player can speed that time flows in the game. Why?

Time-warping was something I realized we needed from the very beginning. Again, the course in spacecraft dynamics served as inspiration here. If you send some probe into space like Voyager that takes years and years to get to where it is going, trying to predict or control its trajectory is like trying to thread a tiny needle. You have to be a NASA engineer to plan these paths. In reality, they are actually using gravity and stealing tiny bits of momentum from other planets in order to propel themselves out of the solar system. And it takes huge amounts of time.

Even when scaled down to the game level, it seemed too much to ask of a player to take a long time over such trajectories in the game play. So with time warping, if you are on a long trajectory you can speed up time and get there faster, whereas if there is a precise maneuver you need to make, then you can slow time down in order to properly execute it. The game reflects that kind of relativistic thinking.

Why did you decide to make players accountable for their actions by causing them to lose mass with every move they make?

You have to be patient and strategic in when you click and how you navigate in the game, and I think that is contributing to the game’s ambient feel, but it again comes down to fundamental physical laws. In game strategy, you need energy to survive, but then you have to apply the principles of momentum and mass. As a player, you want to gain mass, but every time you do that you have to alter your momentum, which in turn alters your mass. There is a feedback loop between mass and momentum, a kind of tight coupling of the two physical principles.

I am quite an environmentalist at heart, and while Osmos doesn’t preach sustainability, the principle certainly affects the design. I think that it certainly teaches players something fundamental about energy use, conservation, and physical laws, but indirectly. Though we seem able to exploit the physical world without affecting ourselves, there is a price to pay. It may not be paid immediately, but there will be a reaction to our consumption eventually. In Osmos, the only way you can succeed is if you recognize that gaining energy requires you to that which you already have wisely.

You have described Osmos as “ambient physics.” What does that mean?

It is definitely a physics game, but I think calling it “ambient physics” is a way of trying to convey to players the nature of the game itself. Physics games are a genre in their own right, but there is not much exploration of slow-paced ambient style in games. It wasn’t an attempt to try and define something new so much as describe what we had. It has a certain chilled, thoughtful feel to it, and I spent probably as much time if not more on the music in the first weeks of game development than anything else. The music had to sound as ambient as it felt to play it. I composed the first song…in fact I think the first electronic song I had ever composed was in the first few weeks of Osmos, and that track did ship with the final game though it is buried quite deeply in it. There are about 10 songs to the game, in addition to sound design. Most of the selection was pre-existing songs that I approached the musician and asked if we could use it for the game, sort of like a curated soundtrack.

In music, there is some ambient that is extremely simple, but with Osmos I was looking for a certain tone, sound, texture and complexity, but no discernable beat. Nothing that would make you move your body, like tap your toe or nod your head. I wanted a beatless soundscape: There is a sense of continual motion, like you are floating in space, and I didn’t want that feeling to be broken by something that compelled you to move. So every song has a spacey feel to it, but it is also richly textured and without a beat.

Have you been surprised by the different analogies people have made about Osmos, whether on the microbial or the cosmic scale?

I remember this one interview I did in Russia where they really seem to appreciate the purity of physics in the game, and I was asked some questions on planetary formation and how there is this flotsam and jetsam floating around in space that conglomerates into blobs, which then form stable objects like planets, galaxies, and stars. And I had to admit, I hadn’t really thought about Osmos that way at first, but planetary formation and how gravity and mass transfer works really came out when I was designing those cosmic levels: I had to think about how surprisingly dense the planetary soup is, if you will, and how these stable bodies form out of different bits and pieces coming together, effectively scaling the same physical properties that inform the rest of the game to the cosmic level.

I have [also] seen people draw parallels that aren’t as obvious as the parallels to biological systems and space travel. I’ve seen people make economic theory connections, like the idea of company conglomerates and the nature of competition. Some think it is a good parallel for the way the mind works in acquiring information and memory. It is open to a broad range of interpretation, and I think that these kinds of parallels can be drawn in a number of ways.

The universe is a lot more complex than Newtonian physics, but then a few of humanity’s greatest achievements have been borne out of the fact that we are able to recognize that there are sometimes incredibly simple, fundamental laws governing some part of the universe. That the universe is rational enough to allow us to have that knowledge is amazing.

Can you describe Osmos in a single sentence?

Osmos is a game for both sides of the brain, merging the scientific and the artistic together. In the opening credits to one version we had the tagline, “Enter the Darwinian world of the galactic mote,” which has a little Darwin and a little galaxy in there, you know? But honestly, I have a hard time describing it. In one way, it is a love letter to Newton, but it is not just that: There is the art and the music—the aesthetics of the game. I think it is hard to get to the fundamental nature of something while also trying to take into account the aesthetics.

The best way to find out what Osmos really is is to play it.

Originally from Scotland, Claire Cameron is an intern with Nautilus and a recent graduate of Columbia Journalism School.