One evening four years ago, photographer Andrea Tese received a phone call from a home-care nurse. Could she come to her grandfather’s house to assess the situation? the nurse asked. Her grandfather had been very ill and had stipulated he did not want to die inside a hospital; he wanted to stay at home. But now he was in severe pain.

Tese came to him with a few Percocet she had left over from a dental procedure, but it didn’t help. She made a hard decision and called for an ambulance. Soon her grandfather left his home for the last time.

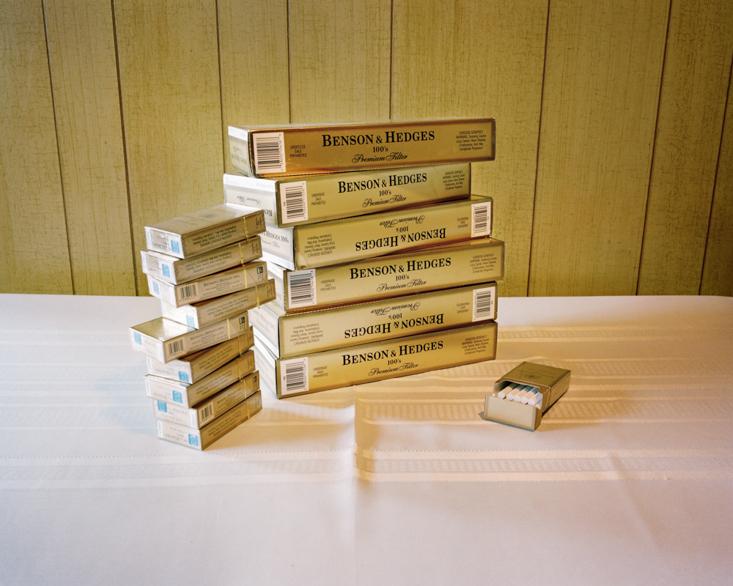

What remained after the passing of Tese’s grandfather was a house left to her and her sister. Inside was evidence of a simple life, well-lived, with a wife he loved and one daughter they were dedicated to raising. There was a final open pack of cigarettes, half a dozen suitcases, a dozen well-used fishing rods, modest bedding and housewares, furniture, and little more. But the sum of these things, later documented by his granddaughter in a series called Inheritance, speaks volumes about their owners and a not-so-distant past when lives were led more modestly. It also shines a light on our current world, in which so many of us aspire to keep up with a consumer culture that most of us cannot really afford.

In a recent phone interview, Tese discussed Inheritance, how she came to document her grandparent’s home the way she did, and expressed her thoughts on our media-swamped, materialistic society.

You took quite some time to shoot Inheritance, from 2010 to 2012. How you were able to do that?

When my maternal grandfather died in 2010—my mom is an only child, and there was only my sister and I—he had no other relatives. My mom also found out she was sick and was in the hospital a lot, and my sister has three small children. There was only me to take care of everything. It was a daunting task to deal with, but it was good because it gave me all of this access and time to work there. It was an ideal situation. I knew I definitely wanted to photograph everything.

These images don’t just show how your grandfather left the house. Things are placed into categories. Why?

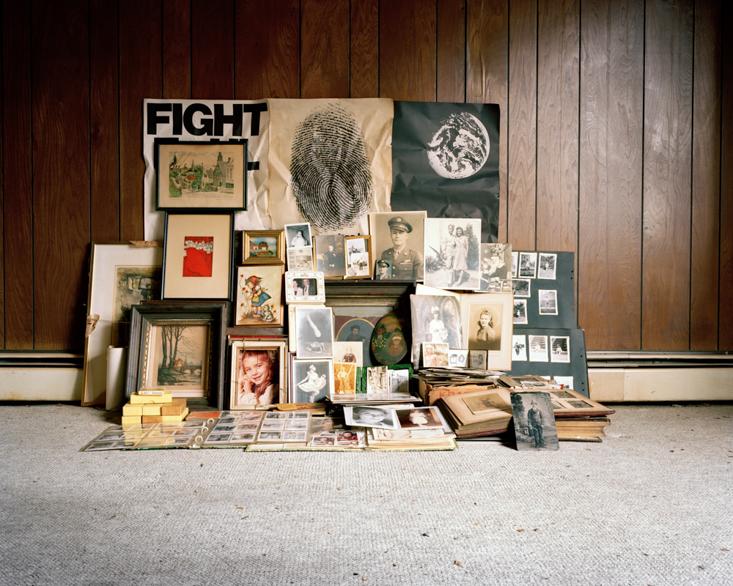

The house is in Maspeth, Queens. My mom and my grandma had grown up there so there were lots of things in the attic and in the basement. I started going through things and found things I didn’t know I was going to find, things that went back one, two, or more generations.

I started putting them in categories…I wanted to photograph the things in interesting ways, so I began arranging them, making installations and sculptures. It went from me thinking about documenting all of these things that belonged to them [both grandparents], to making it something that was more active. Finally, there was a lot of me that went into it. It was not just about what they chose to keep. I was giving these objects a new purpose, a new life, before they moved on to obscurity again and into the trash.

What do you learn from this process?

I was able to focus on the work but not every day. Let’s say I found something particularly sad. I would get emotional. I was emotional. It was a constant reminder that time marches on and we’re going to die. Thinking of that upsets me. Categorizing, arranging, photographing, is a way to cope or try to assert some control over death and the loss of people I care about. This was, and is, what I do. It’s my art. The motivation wasn’t sentimental; it wasn’t to let everyone know what a wonderful man he was. The motivation was the existential, to fight the impermanence of life.

Psychologists say there are five stages of loss and grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Do any of these stages describe your work with Inheritance?

I wouldn’t disagree that there are those stages, but I don’t know that they’re in that order and I don’t know if they’re the only stages. The denial part I’m going through. Denial of letting his, my grandmother, mine, everyone’s memory slip away, letting it disappear. I’ll always be in denial, or maybe this is my bargaining.

Why did you want to examine their possessions so deeply?

I got to thinking, my grandfather had all these things he kept because they had some importance to him, and then I was only going to keep what was important or valuable to me, and then my children would do the same. So maybe just a few of those objects of his would make it into their hands, and then maybe it’s only a photograph, and probably of someone they don’t know.

I’m trying to prolong the memory of my grandparents and give them some permanence. It’s sad that someone’s impression on the world is so temporal, or so ephemeral. If there’s no permanent record, if you weren’t a writer or in a public position, the memory of you fades, there’s little left behind.

What did you learn about your grandparents through this process that you didn’t know? Were there any surprises?

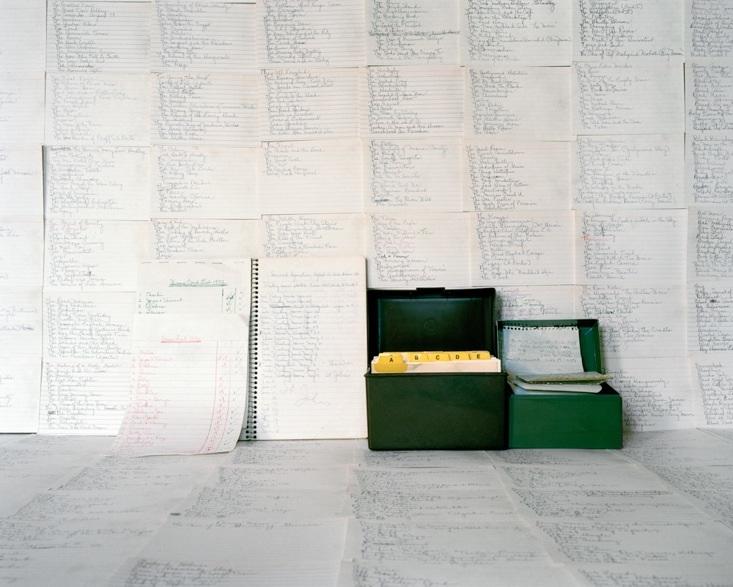

The project centered around my grandfather’s death, but in 1997 my grandmother, his wife, died. He got rid of most of her things then, but he kept some things. There was something he kept that I had no idea my grandmother did. I found a file box filled with her lists. I’m a lister to, but she wrote down everything she read and watched and we had no idea she did this. It makes sense, though, because there’s a bit of an OCD nature in the family.

Why do you think he kept these lists?

It obviously meant a lot to her. It was a lifelong project for her. I thought a lot about that—why’d she do it—I think it was her way of keeping a diary. She wrote down all the articles and books she read [and television programs and movies she watched], and since she had to leave school early, maybe it was a continuation of her education.

I know that some of obsessive compulsiveness is about trying to create order over a life. This was a record of what she did and what she watched and maybe she meant to leave a record. I wish I’d known she’d done that. Obviously my grandfather knew about it. I can see them in my mind. They would be sitting in the living room and she’d take out her box of flashcards and write down something she’d just watched. And so he knew.

That would probably be impossible to do today, right?

Today we have so much consumer media. We take all of this media in all the time. It comes in, it’s in the background, it’s a big buzz around us. It’s so big I don’t retain much of it. I don’t remember the premise. She was in that generation that would watch something, take it all in, write it down, record it, and log it. It meant more.

Do you try to live simply or are you more of a consumer?

I have my mom’s tendencies in that I would rather buy one thing that’s maybe a little more expensive but I want to keep it a long time. I still take home leftovers, and bread rolls off the table [at a restaurant] and eat them for breakfast. I’m just that kind of person. I got that from her and she got that from them. They didn’t have any money. They were simple people by any kind of modern standards, but their furniture was of good quality. They picked out their favorite things and then put it on layaway and eventually it was theirs and it’s still in perfect condition! People want things quick, cheap, and easy today, and manufacturers have to keep up by making things poorly just so people can get rid of them again.

Does this kind of thinking influence you to use film in your photography?

Film is no longer a consumer problem. There are so few options and resources left. Thank god the film I like using [Kodak Portra] is still being made. I love the aesthetic of film. I like antiques. I like older things, the look of them, the feel of them.

People who use digital, they take so many shots. There will be literally thousands and thousands of images taken and then they just have to choose the one that works the best. Whereas with film, I’ll take ten to twelve shots, with a slight change of perspective and angle. This gives a different quantity and a different pace. With digital, there is so much more quantity, a much higher pace.

With Instagram, you start looking and then you realize you’ve fallen into it for an hour, you get sucked in.

Heather Sparks explores art and science at Science Sparks Art. She studied molecular genetics at The Ohio State University, has a graduate degree in science journalism from New York University, and currently lives in Brooklyn.