While Frankfurt International Airport is among the world’s biggest international air hubs, locals still call it “Waldflughafen,” meaning the airport in the woods. Situated in one of the most diverse ecosystems in the Rhein-Main region of Germany, the surrounding forests served as hunting grounds for the local aristocracy for hundreds of years and, protected from urbanization, preserved a dazzling variety of species. Transforming this diversity of land use patterns into a major international airport meant disrupting that ecosystem, altering the migration patterns and “homes” of countless animals and plants. But the story of Frankfurt Airport’s borders is as much about the creation of homes as it is about their destruction. The modern airport, and Frankfurt Airport in particular, gives us a unique window onto the many tensions implicit in any definition of home, and shows us how the construction of home is essentially intertwined with the production of borderlands. These borders show us that home is not something that is given, but rather something that is made and managed, transitory and subject to conflict.

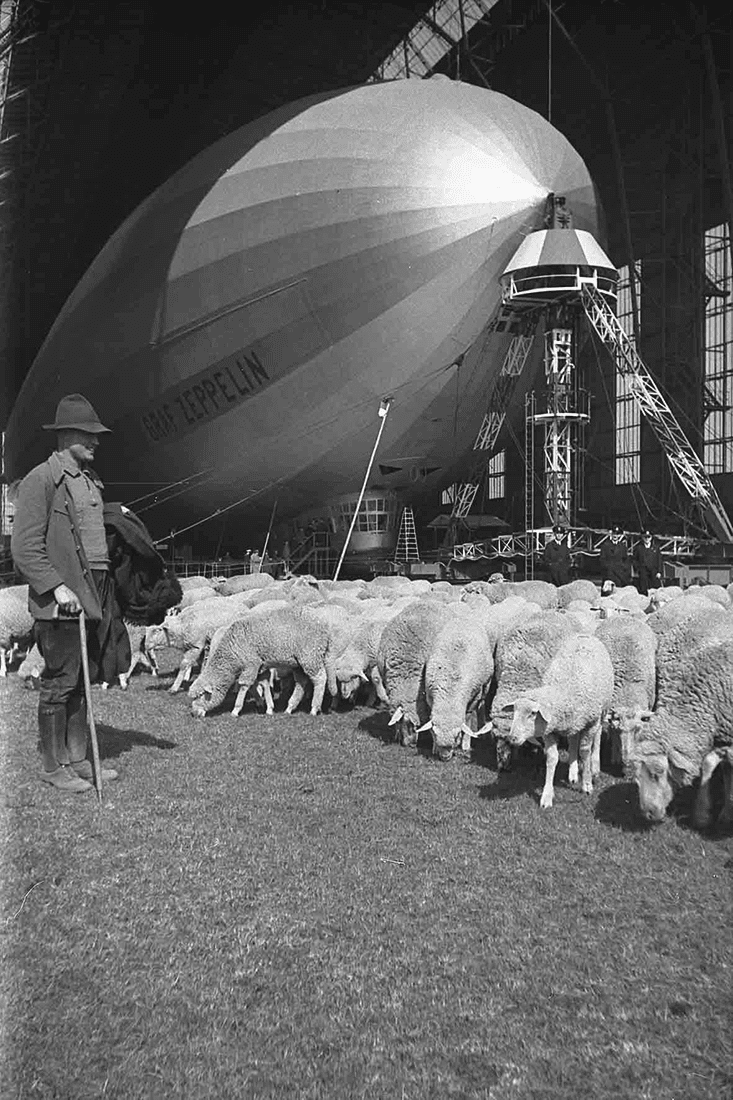

When Frankfurt Airport opened in 1936, the diversity of the surrounding area also extended to the airport grounds. Agriculture on airport property was common until the late 1940s, and was in some ways symbiotic with air transport. The airport boasted its own flock of more than 1,000 sheep, looked after by an “airport shepherd” whose job it was to ensure that the grass on the runways was mowed and its soil was trodden down. The land around the then-grassy runways was used for the cultivation of vegetable and grain crops. With the arrival of jet airplanes, however, runways became concrete, and animals became more of a hazard.

In 1960, the airport erected a fence to keep deer and other animals away from the planes and runways. Together with a change in hunting regulations, this fence transformed the airfield into a private hunting ground. Any and all animals on airport lands that might jeopardize planes were simply shot—especially birds. By the 1970s, this heavy-handed approach had transformed into a more sophisticated and peaceful method of habitat management. Specific grass seeds were selected in order to produce meager and unattractive environments for wildlife, forcing mice and birds off the airport property to look for food elsewhere. The mixture of seeds was continuously altered to prevent animals from adapting. Ponds were avoided during construction and maintenance projects so that birds would not be drawn in for a rest or to satisfy their thirst. In short, says the current Frankfurt Airport forest ranger, Thomas Müntze, the ideal was to create “a boring ecosystem.”

Producing this “boring ecosystem,” managed by the ranger, is an important part of the story of the creation of Frankfurt Airport. This is because it was closely intertwined with the rise of the airport as a complex borderland and security area. Consistently, biological boundaries have been subject to political conflict. In the early 1980s, when the airport tried to expand further onto neighboring land, local residents protested again the destruction of “their” woods, which they saw as an integral part of their homeland. This movement gained considerable recognition, and served as a nucleus for the formation of the German Green Party. Protesters built temporary hut villages in forests that were slated to be cleared for the construction of Startbahn West, a new 4-kilometer runway.

This human reaction to the politics of biotope management soon fed back into the creation of new borders, and new interactions with animals. The protests prompted the construction of walls to shield construction sites from political protestors. Additional walls were built to reduce noise pollution due to the existing runways. And after police forced the protesters to leave the woods, the protection of biodiversity in the surrounding areas—many of them designated as nature reserves—was mandated as part of the agreement for expanding airport operations. These areas included the Mönchbruch reserve located immediately next to one of the airport runways.

However, the regulation and design of these nature reserves continued to betray their status as a form of curated nature that was uninhabitable to human residents and instrumental to the airport’s safety and efficiency. One set of regulations, for example, restricted the number of birds drawn to local lakes. Human populations were also managed. An old hunting lodge on one of the reserves served from the late 1980s as a temporary home for asylum seekers and migrant workers. In 2003, they were forced to vacate the space in deference to the ecological “purity” of the natural reserve.

At the same time, new life began to spring up in border interstices. Between the walls built to keep protesters out and the airport fences designed to keep animals out, a new variety of plants species began to settle—many of which were attractive to birds, whose populations the airport was trying so hard to manage. The land lying just beyond the reach of rangers and regulation became a safe place, and a new home.

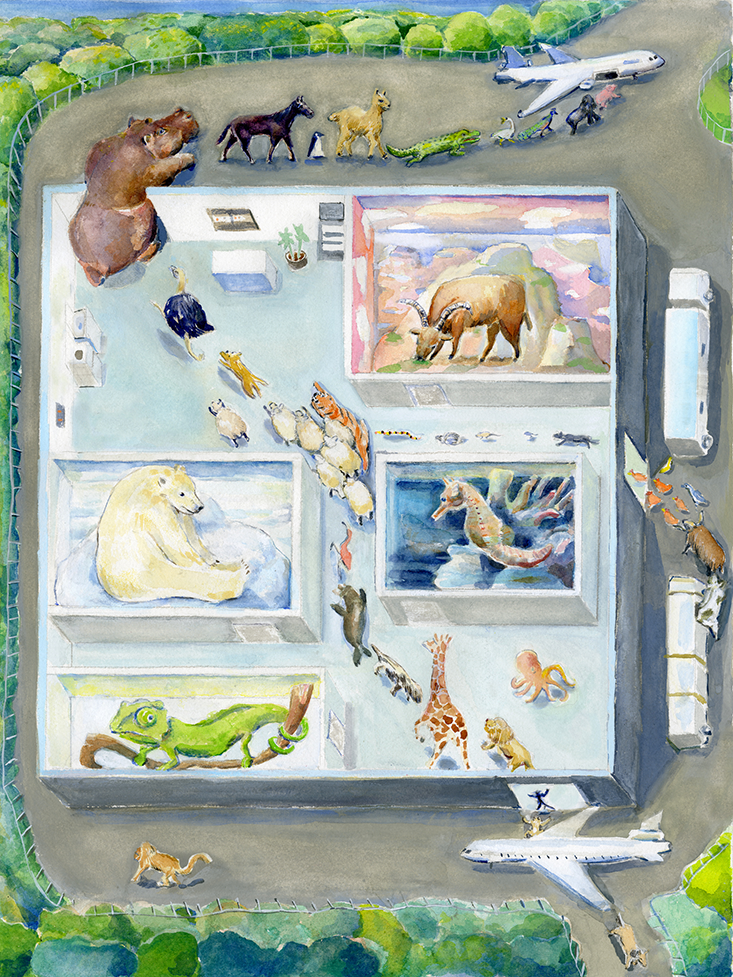

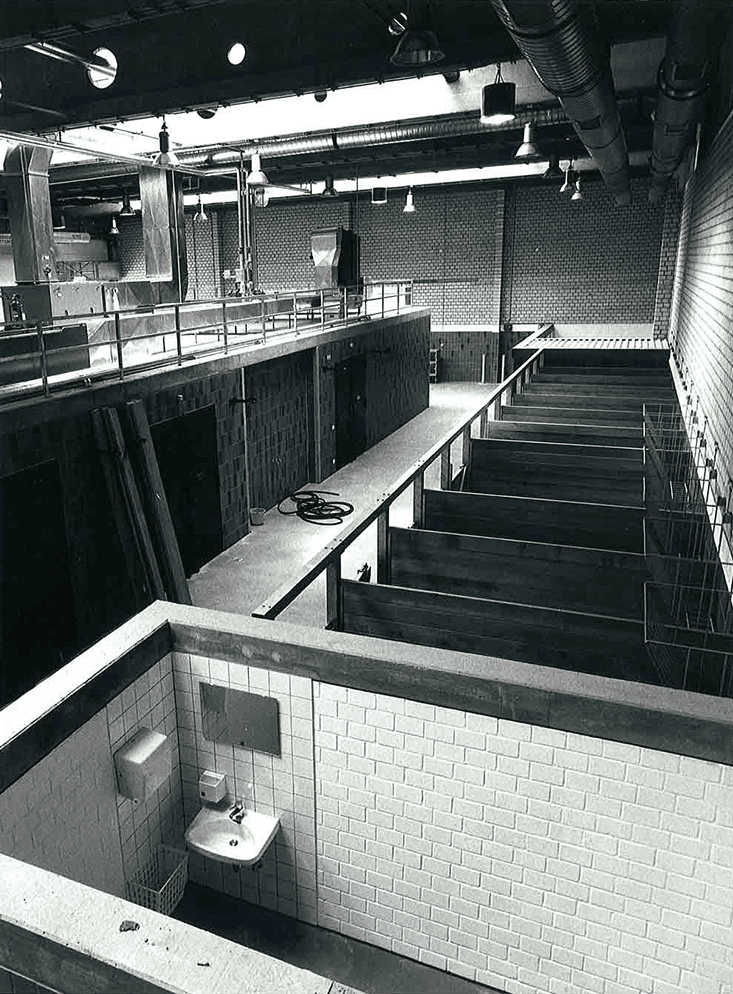

While animals, plants, and people settled and resettled near the airport borders, the airport was busy building a new series of planned and regulated homes. The first such home was a temporary living space for animals traveling through the airport. Formerly called the “animal room” and later renamed the “animal lounge,” it was built in the basement of the airport’s new cargo building in the early 1960s. Individual stalls accommodated the needs of the animals being transported, whether they were pets, zoo animals, or racehorses. Having chased away many of the area’s natural animal residents, locals developed a fascination with the airport’s “sanctioned” animals, many of which came through the animal lounge. Local and national newspapers regularly reported on animal air cargo throughout the 1950s and 60s. “A horse disembarked,” noted a newspaper in 1962 on the arrival of a racehorse on a PANAM flight, before editorializing that the “image seemed like the realization of a surrealist joke.”

Of course, things did not always go according to plan. In the early 1960s, all cargo center staff joined in the search for an escaped cougar in the cellars of the cargo building, until someone noticed that the cougar had already boarded a plane. Twenty years later, the head of the animal lounge, armed with a revolver, had to search the whole cargo area for a baboon on the run. Perhaps most memorable was the story of Nocturno, a racehorse on his way to represent Puerto Rico at the Olympic Games in Munich. Although Nocturno had spent the two years prior to his arrival training in Virginia, an epidemic had recently spread through his island home and it took more than a week to prove that he had not been in contact with any animals there.

Unfortunately, the animal room was not designed for this length of stay, nor for anything like the intensive conditioning regime that an Olympic racehorse was accustomed to. Eventually, a compromise was struck: At night, when airplanes stood still, Nocturno was “carried with a blue light driving transporter to the meager grassland” between the runways. Here was a new kind of interstitial and temporary animal habitat within the same borders that had cleared away most other forms of animal life.

It took some time to establish a more professionalized and standardized treatment of animal cargo. In 1971, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) standardized procedures for animal transportation by publishing an annually updated Live Animal Regulations (LAR) guide. The guide addressed species-appropriate containers, and was developed with the help of an expert group of biologists, veterinarians, economists, and logistic specialists—many of them from Frankfurt. These groups still meet twice a year to evaluate statistics and suggest improvements to increase the productivity of animal transportation, and decrease the number of “dead on arrival” animals, which has dropped from almost 20 percent in the 1980s to about 1 percent today. The animal lounge has also been dramatically improved, moving from the cargo building basement to a newly-built area at the airport periphery, and serving as an animal border checkpoint for the European Union with more than 25 veterinarian shift workers on staff.

The tension between practices of exclusion and inclusion is mirrored by the complexity of the role of the airport forest ranger. The ranger is a highly romanticized figure in German culture. It is associated with the German woods, and a reminder of the good old days, a mythic representative of traditional ways of life and untouched homelands. At the same time, the ranger’s profession has long included economization of the woods. And, like all rangers, the Frankfurt airport rangers have hardly left the lands under their management untouched. Apart from having been part and parcel of the airport’s animal management programs, they have been hired to coordinate the cutting of trees for airport expansion.

The ranger, in this regard, has become what Bruno Latour describes in his book We Have Never Been Modern as a “hybrid” figure: A paradoxical representative of the modern constitution. Modernity, according to Latour, comes with a “great divide” between nature and society. This is a divide that is incessantly repeated and upheld through border practices that, in turn, also give rise to unintentional hybrids. Shepherds and rangers are such hybrids. The Frankfurt airport ranger is a keeper and protector of the land, but also a hunter who is allowed to use weapons at the airport, a manager and habitat engineer, and an enabler of the global commerce that flows through modern airports every day.

The modern airport lies at the intersection of many kinds of borders, including national, ecological, interspecies, economic, and political. We should not be surprised that homelands always create borderlands. In facilitating the global circulation of capital, airports interrupt local ecologies, communities, and politics in their production of very specific, hybrid, interstitial ecologies—often creating temporary and precarious “homes” for both humans and non-humans. The production of a comfortable traveling experience for some comes at the expense of stable homes for others. By studying these homes, we discover something about the definition of home itself—home lies somewhere between inhabiting and circulating, belonging and destruction. Home is not necessarily a comfort zone. As Gloria Anzaldúa has put it in her work on the Mexican-American border: “No, not comfortable but home.”

Susanne Bauer (Goethe University Frankfurt), Sarah Blacker (University of Alberta), Nils Güttler (University of Erfurt), and Martina Schlünder (Ludwik Fleck Center, ETH Zurich) are historians and sociologists of science, working collectively on the environmental history of Frankfurt airport.