Jorge Louis Borges once described an empire that wanted to build a map. But the maps they had seen before were not precise enough. They had too much compression and approximation. There was too much inexactitude. And so the empire eventually made a map of the empire that was the size of the empire, and “coincided point for point with it.” But even this map, the size of the empire it described, could not capture the totality of experiences within the empire. Sure, it could tell you exactly where the castle is, or which roads intersected with which others and where, but it couldn’t, for example, tell you what that intersection smelled like.

Most maps, like the life-size one of Borges’ empire, are of the visual sort. They tell us the location of buildings and roads and how to use one to get to the other. But they don’t tell us what that feels like, or smells like, or sounds like. That’s where sensory mapmakers come in. These sense cartographers want to give you a sense for a place beyond grids and lines on a page or a screen.

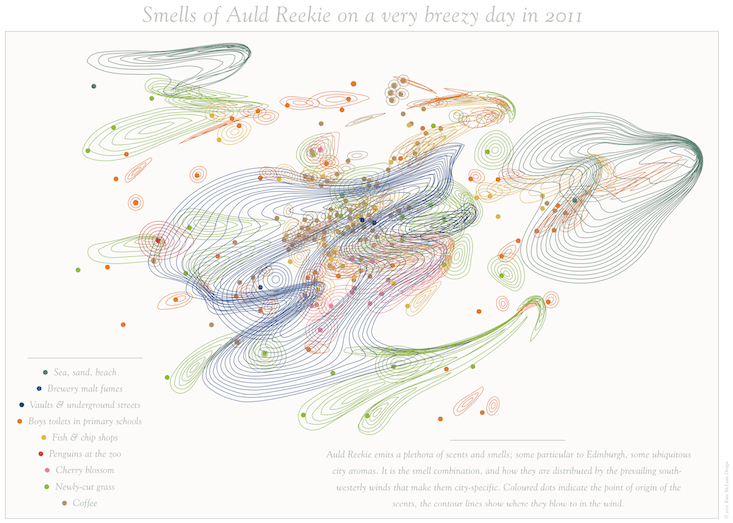

Take Kate McLean for example. McLean is a self-described “designer, cartographer, photographer, and smell collector.” She has built smell maps of places like New York, Paris, and Edinburgh.

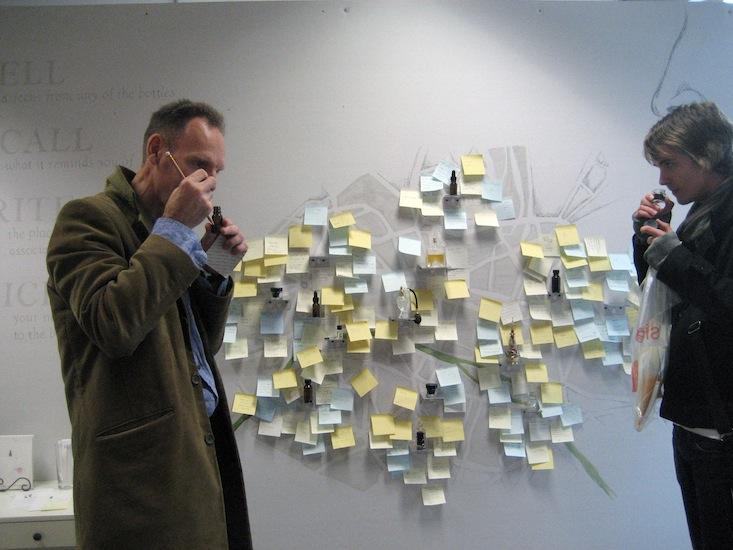

Here, McLean recreated an area of Paris with little jars and vials to sniff from.

And in this map, she captures the smells of Edinburgh (“Auld Reekie”) on a breezy day.

McLean’s maps are all very physical—she prints them and builds them as pieces of art. But other mappers have taken to the Internet and attempted to harness the power of the crowd to capture the smells of a city. In the Czech Republic, students developed the SmellMap, an iPhone app that lets you share your olfactory experiences with those around you. The project won the Czech National Award for Student Design last year.

For McLean, there is one experience that has eluded her: sound. For her show in Edinburgh, she did some research on the soundscapes of the city. “The bird movement, wing flapping and landing in the Princes’ Street gardens after the daily 1pm cannon shot, car tires on the Royal Mile cobbles and locals talking in a tiny pub,” she says. Between technical and time constraints, though, the sound map was simply beyond her grasp.

But other sensory mappers have made more progress in encoding audio information into a visual map. The British Museum has a map dedicated to the different accents around Britain. Sound Around You, a project from the University of Salford, in Manchester, England, encourages people to upload sounds of their surroundings to give others across the world a sense for not just the lay of the land, but the sound of it too. Radio Aporee does much of the same, showing visitors the most recent uploaded soundscapes.

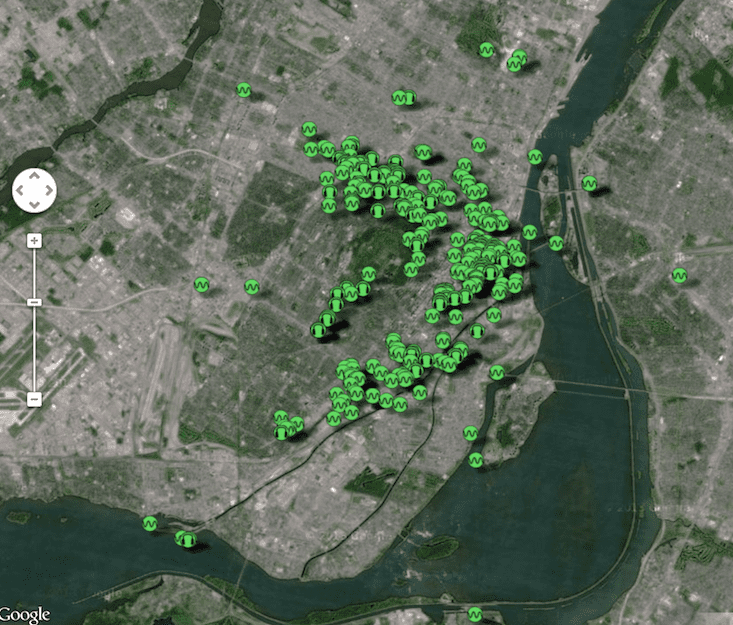

Montreal has its own sound map as well. Their website explains that sound maps “are in many ways the most effective auditory archive of an environment, touching on aspects political, artistic, cultural, historical and technological.”

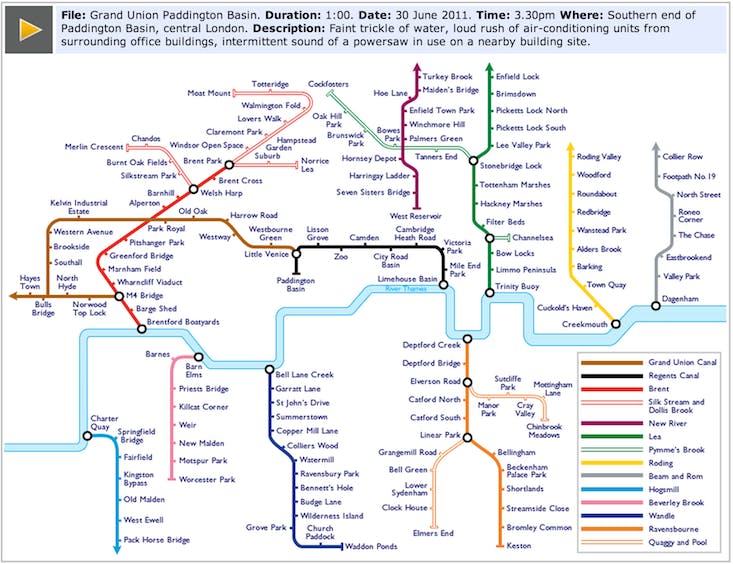

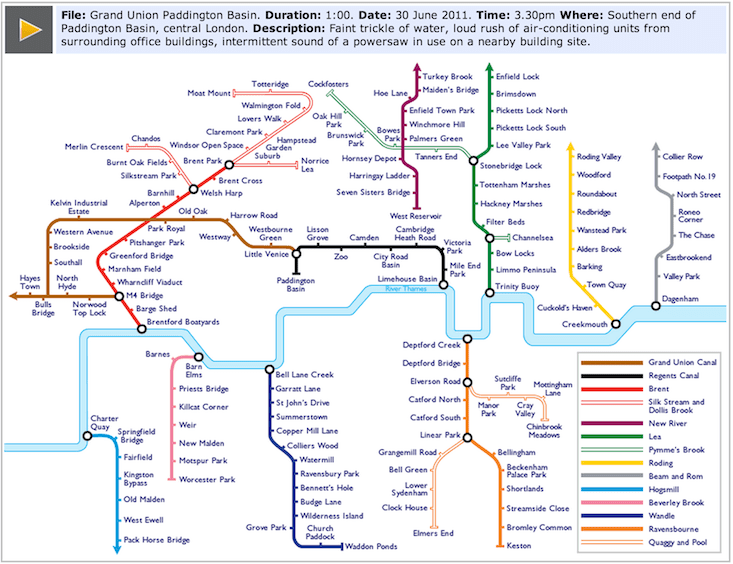

In London there’s a sound map of the underground waterways that flow beneath the city.

And for those interested in sound tourism, there’s Sonic Wonders, a whole website dedicated to unusual and captivating sounds, including everything from the Great Stalacpipe Organ of Virginia to the Booming Sand Dunes of Kazakhstan.

You won’t find any of these maps at the local tourism office or in your rental car’s glove compartment. But if you want to understand a city past its intersections and buildings, sensory cartography can provide a different kind of understanding than you’d get from a road map.

Rose Eveleth is Nautilus’ special media manager.