Despite

their great distance from Earthbound politics, exoplanets were the

topic of a joint

hearing

on May 9th of the House space and research subcommittees. The recent

discovery of a trio of temperate super-Earths

was the hearing’s impetus, but most of the discussion was devoted

to future prospects—chiefly, how and when scientists might learn

whether any exoplanet actually harbors an Earth-like environment or

even alien life. Leaders from NASA,

the National

Science Foundation,

and the SETI

Institute

all spoke of steady progress toward those goals, though their sunny

forecasts were arguably based more on faith than facts. Right now,

speculating about the environment of any potentially habitable

exoplanet is rather like guessing an individual’s facial features

based only on their height and weight, and without some sea change in

policy or funding, this situation seems set to persist for decades to

come.

This

may be surprising considering that astronomy is in the midst of an

exoplanet boom, a golden age of extrasolar discovery, and a host of

current and upcoming ground- and space-based projects will ensure the

boom continues for years to come. We are learning more than ever

before about the formation, distribution, and evolution of

exoplanets. The Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes can already

crudely study the upper atmospheres of select hot, giant exoplanets

that happen to “transit,” or cross the faces of, their stars, as

seen from here. The James

Webb Space Telescope (JWST),

which may launch as early as 2018, could do

the same [pdf] for some smaller, cooler exoplanets that orbit and transit nearby

stars, while also snapping family portraits of nascent and young

planetary systems. Though nearing the end of its life, the Kepler

mission has found nearly 3,000 likely exoplanets transiting faraway

stars in a single swatch of sky, and a follow-up, all-sky mission

called TESS

should launch in 2017 to look for more transiting worlds, some of

which could then be closely investigated by JWST. These are only a

few of the space-based planet-finders; there are too many other new

and worthwhile projects to list here.

And

yet of all the projects, instruments, and telescopes now operating or

soon to debut, not one is capable of delivering what the search for

extrasolar life most requires: The atmospheric spectra of any

potentially habitable planets around a representative sample of the

Sun’s neighboring stars. Whenever starlight shines through or

scatters off a planet’s atmosphere, the atoms and molecules in the

air absorb some of the light, leaving their faint chemical

fingerprints. Astronomers can discern these fingerprints by gathering

enough of that light to create a rainbow-like spectrum. A planet’s spectrum can help determine whether

that world is habitable or even inhabited. The spectral fingerprints

of water vapor or carbon dioxide, two powerful greenhouse gases,

would signpost a warm, wet, rocky world, and an abundance of oxygen

and methane could be evidence of a biosphere of photosynthetic plants

and chemosynthetic bacteria. With such tantalizing clues in hand,

more in-depth telescopic observations could eventually reveal even

more secrets, as across the light-years astronomers map the

distribution of lands, seas, and weather patterns of Earth-like alien

planets.

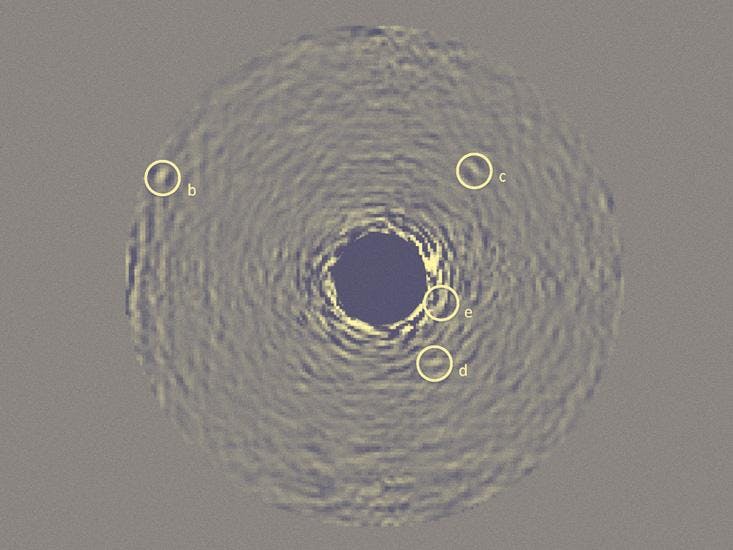

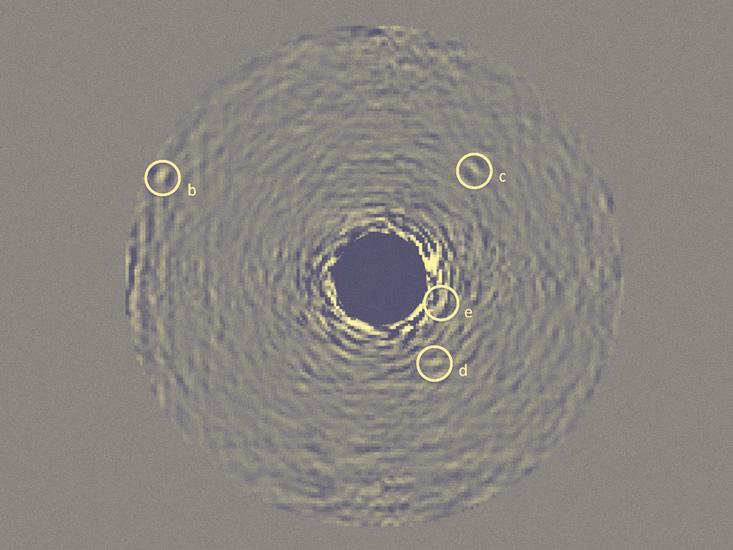

The exoplanet’s spectrum must be painstakingly sifted from a flood of raw starlight some ten million to ten billion times brighter. Astronomers have already demonstrated a handful of ways to achieve this.

As

straightforward as this all sounds, there is an inconvenient

underlying truth that few planet-hunters wish to admit—particularly

in front of deficit-weary taxpayers: Pursuing the light of other

living worlds will almost unavoidably be a multi-billion-dollar

venture.

Barring

various extremely

implausible

scenarios, any conceivable Earth-like exoplanet will be a small, dim

object very close to its much brighter, larger star. Its spectrum

must be gathered photon by photon, with each individual particle of

planetary light painstakingly sifted from a flood of raw starlight

some ten million to ten billion times brighter. As difficult as this

“starlight suppression” sounds, astronomers have already devised

and lab-demonstrated a handful of ways to achieve it, using

techniques like coronagraphy

and interferometry.

(See a summary

of some of the methods here

[pdf].) The bigger, more fundamental problem is that obtaining the

spectrum from just one potentially habitable exoplanet is unlikely to

be enough; satisfying our search for life, gaining some inkling of

our cosmic context, will probably require surveying hundreds or

thousands of worlds in the relatively short timespan of one

space-telescope mission. To quickly, efficiently perform such a

search requires one or more very large, very sophisticated

starlight-suppressing space telescopes—telescopes that currently

have no funding and very little public awareness.

I

would say that in addition to being “very large” and “very

sophisticated,” these telescopes are also “very expensive”—except

on federal or national scales that’s simply not the case. Assuming

it would take some $5 billion to develop, build, launch, and operate

one such space observatory, any number of telling comparisons present

themselves. That’s less than what the U.S. government spends for a

few weeks of its military presence

in the Middle East

and Central Asia, or for a dozen F-22

fighter jets.

As a nation we spend more each year on chocolate

candy.

The point of course isn’t that we should eliminate defense spending

or stop buying candy bars, but simply that the great wealth of our

world is more than adequate to bestow a priceless gift to all

humankind in perpetuity. What our political leaders and philanthropic

billionaires should understand is that the discovery of other Earths

and other life beyond our solar system is something that can happen

only once in our history, and something that is just now within our

grasp. With just a relatively tiny fraction of public or private

funding and effort, we could all soon see a day where anyone on Earth

can look up to some bright star in the night sky and know a world

circles there from which someone may be looking right back.

Wouldn’t

that be worthwhile?

Lee Billings is a freelance writer living in New York City. Five Billion Years of Solitude, his book on the search for Earth-like exoplanets, will be published this October by Current/Penguin.