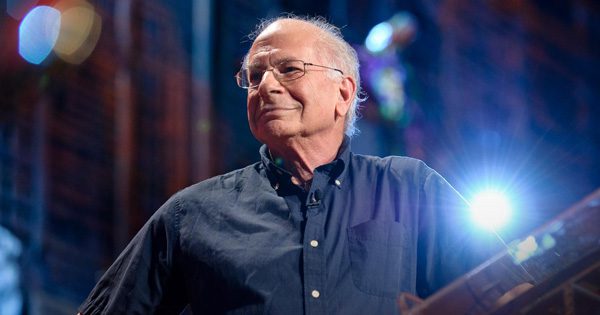

Legendary Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman is one of the most influential thinkers of our time. A Nobel laureate and founding father of modern behavioral economics, his work has shaped how we think about human error, risk, judgement, decision-making, happiness, and more. For the past half-century, he has profoundly impacted the academy and the C-suite, but it wasn’t until this month’s highly anticipated release of his “intellectual memoir,” Thinking, Fast and Slow (public library), that Kahneman’s extraordinary contribution to humanity’s cerebral growth reached the mainstream — in the best way possible.

Legendary Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman is one of the most influential thinkers of our time. A Nobel laureate and founding father of modern behavioral economics, his work has shaped how we think about human error, risk, judgement, decision-making, happiness, and more. For the past half-century, he has profoundly impacted the academy and the C-suite, but it wasn’t until this month’s highly anticipated release of his “intellectual memoir,” Thinking, Fast and Slow (public library), that Kahneman’s extraordinary contribution to humanity’s cerebral growth reached the mainstream — in the best way possible.

Absorbingly articulate and infinitely intelligent, Kahneman examines what he calls the machinery of the mind — the dual processor of the brain, divided into two distinct systems that dictate how we think and make decisions. One is fast, intuitive, reactive, and emotional. (If you’ve read Jonathan Haidt’s excellent The Happiness Hypothesis, as you should have, this system maps roughly to the metaphor of the elephant.) The other is slow, deliberate, methodical, and rational. (That’s Haidt’s rider.)

The mind functions thanks to a delicate, intricate, sometimes difficult osmotic balance between the two systems, a push and pull responsible for both our most remarkable capabilities and our enduring flaws. From the role of optimism in entrepreneurship to the heuristics of happiness to our propensity for error, Kahneman covers an extraordinary scope of cognitive phenomena to reveal a complex and fallible yet, somehow comfortingly so, understandable machine we call consciousness. He paints the backdrop for his inquiry:

Much of the discussion in this book is about biases of intuition. However, the focus on error does not denigrate human intelligence, any more than the attention to diseases in medical texts denies good health… [My aim is to] improve the ability to identify and understand errors of judgment and choice, in others and eventually in ourselves, by providing a richer and more precise language to discuss them.

Among the book’s most fascinating facets are the notions of the experiencing self and the remembering self, underpinning the fundamental duality of the human condition — one voiceless and immersed in the moment, the other occupied with keeping score and learning from experience. Kahneman writes:

I am my remembering self, and the experiencing self, who does my living, is like a stranger to me.

Kahneman spoke of these two selves and the cognitive traps around them in his fantastic 2010 TED talk:

There are several cognitive traps that … make it almost impossible to think straight about happiness… The first of these traps is a reluctance to admit complexity. It turns out that the word “happiness” is just not a useful word anymore, because we apply it to too many different things…

The second trap is a confusion between experience and memory… between being happy in your life, and being happy about your life or happy with your life. And those are two very different concepts, and they’re both lumped in the notion of happiness.

And the third is the focusing illusion, and it’s the unfortunate fact that we can’t think about any circumstance that affects well-being without distorting its importance.

What’s most enjoyable and compelling about Thinking, Fast and Slow is that it’s so utterly, refreshingly anti-Gladwellian. There is nothing pop about Kahneman’s psychology, no formulaic story arc, no beating you over the head with an artificial, buzzword-encrusted Big Idea. It’s just the wisdom that comes from five decades of honest, rigorous scientific work, delivered humbly yet brilliantly, in a way that will forever change the way you think about thinking.

Thanks, Sean