Poggio Bracciolini might just be the most important man you’ve never heard of.

Poggio Bracciolini might just be the most important man you’ve never heard of.

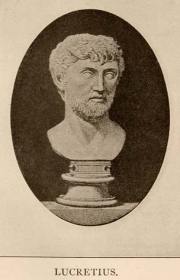

One cold winter night in 1417, the clean-shaven, slender young man pulled a manuscript off a dusty library shelf and could barely believe his eyes. In his hands was a thousand-year-old text that changed the course of human thought — the last surviving manuscript of On the Nature of Things, a seminal poem by Roman philosopher Lucretius, full of radical ideas about a universe operating without gods and that matter made up of minuscule particles in perpetual motion, colliding and swerving in ever-changing directions. With Bracciolini’s discovery began the copying and translation of this powerful ancient text, which in turn fueled the Renaissance and inspired minds as diverse as Shakespeare, Galileo, Thomas Jefferson, Einstein and Freud.

In The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, acclaimed Renaissance scholar Stephen Greenblatt tells the story of Bracciolini’s landmark discovery and its impact on centuries of human intellectual life, laying the foundations for nearly everything we take as a cultural given today.

This is a story [of] how the world swerved in a new direction. The agent of change was not a revolution, an implacable army at the gates, or landfall of an unknown continent. […] The epochal change with which this book is concerned — though it has affected all our lives — is not so easily associated with a dramatic image.

Central to the Lucretian worldview was the idea that beauty and pleasure were worthwhile pursuits, a notion that permeated every aspect of culture during the Renaissance and has since found its way to everything from design to literature to political strategy — a worldview in stark contrast with the culture of religious fear and superstitions pragmatism that braced pre-Renaissance Europe. And, as if to remind us of the serendipitous shift that underpins our present reality, Greenblatt writes in the book’s preface:

Central to the Lucretian worldview was the idea that beauty and pleasure were worthwhile pursuits, a notion that permeated every aspect of culture during the Renaissance and has since found its way to everything from design to literature to political strategy — a worldview in stark contrast with the culture of religious fear and superstitions pragmatism that braced pre-Renaissance Europe. And, as if to remind us of the serendipitous shift that underpins our present reality, Greenblatt writes in the book’s preface:

It is not surprising that the philosophical tradition from which Lucretius’ poem derived, so incompatible with the cult of the gods and the cult of the state, struck some, even in the tolerant culture of the Mediterranean, as scandalous […] What is astonishing is that one magnificent articulation of the whole philosophy — the poem whose recovery is the subject of this book — should have survived. Apart from a few odds and ends and secondhand reports, all that was left of the whole rich tradition was contained in that single work. A random fire, an act of vandalism, a decision to snuff out the last trace of views judged to be heretical, and the course of modernity would have been different.

Illuminating and utterly absorbing, The Swerve is as much a precious piece of history as it is a timeless testament to the power of curiosity and rediscovery. In a world dominated by the newsification of culture where the great gets quickly buried beneath the latest, it’s a reminder that some of the most monumental ideas might lurk in a forgotten archive and today’s content curators might just be the Bracciolinis of our time, bridging the ever-widening gap between accessibility and access.

Hat tip My Mind on Books