“The universe is made of stories, not atoms,” poet Muriel Rukeyser famously proclaimed. The stories we tell ourselves and each other are how we make sense of the world and our place in it. Some stories become so sticky, so pervasive that we internalize them to a point where we no longer see their storiness — they become not one of many lenses on reality, but reality itself. And breaking through them becomes exponentially difficult because part of our shared human downfall is our ego’s blind conviction that we’re autonomous agents acting solely on our own volition, rolling our eyes at any insinuation we might be influenced by something external to our selves. Yet we are — we’re infinitely influenced by these stories we’ve come to internalize, stories we’ve heard and repeated so many times they’ve become the invisible underpinning of our entire lived experience.

“The universe is made of stories, not atoms,” poet Muriel Rukeyser famously proclaimed. The stories we tell ourselves and each other are how we make sense of the world and our place in it. Some stories become so sticky, so pervasive that we internalize them to a point where we no longer see their storiness — they become not one of many lenses on reality, but reality itself. And breaking through them becomes exponentially difficult because part of our shared human downfall is our ego’s blind conviction that we’re autonomous agents acting solely on our own volition, rolling our eyes at any insinuation we might be influenced by something external to our selves. Yet we are — we’re infinitely influenced by these stories we’ve come to internalize, stories we’ve heard and repeated so many times they’ve become the invisible underpinning of our entire lived experience.

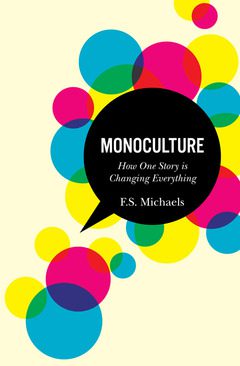

That’s exactly what F. S. Michaels explores in Monoculture: How One Story Is Changing Everything (public library) — a provocative investigation of the dominant story of our time and how it’s shaping six key areas of our lives: our work, our relationships with others and the natural world, our education, our physical and mental health, our communities, and our creativity. Michaels writes:

The governing pattern a culture obeys is a master story– one narrative in society that takes over the others, shrinking diversity and forming a monoculture. When you’re inside a master story at a particular time in history, you tend to accept its definition of reality. You unconsciously believe and act on certain things, and disbelieve and fail to act on other things. That’s the power of the monoculture; it’s able to direct us without us knowing too much about it

During the Middle Ages, the dominant monoculture was one of religion and superstition. When Galileo challenged the Catholic Church’s geocentricity with his heliocentric model of the universe, he was accused of heresy and punished accordingly, but he did spark the drawn of the next monoculture, which reached a tipping point in the seventeenth century as humanity came to believe the world was fully knowable and discoverable through science, machines and mathematics — the scientific monoculture was born.

Ours, Michaels demonstrates, is a monoculture shaped by economic values and assumptions, and it shapes everything from the obvious things (our consumer habits, the music we listen to, the clothes we wear) to the less obvious and more uncomfortable to relinquish the belief of autonomy over (our relationships, our religion, our appreciation of art). She explains:

A monoculture doesn’t mean that everyone believes exactly the same thing or acts in exactly the same way, but that we end up sharing key beliefs and assumptions that direct our lives. Because a monoculture is mostly left unarticulated until it has been displaced years later, we learn its boundaries by trial and error. We somehow come to know how the master story goes, though no one tells us exactly what the story is or what its rules are. We develop a strong sense of what’s expected of us at work, in our families and communities — even if we sometimes choose not to meet those expectations. We usually don’t ask ourselves where those expectations came from in the first place. They just exist — or they do until we find ourselves wishing things were different somehow, though we can’t say exactly what we would change, or how.” ~ F. S. Michaels

Neither a dreary observation of all the ways in which our economic monoculture has thwarted our ability to live life fully and authentically nor a blindly optimistic sticking-it-to-the-man kumbaya, Michaels offers a smart and realistic guide to first recognizing the monoculture and the challenges of transcending its limitations, then considering ways in which we, as sentient and autonomous individuals, can move past its confines to live a more authentic life within a broader spectrum of human values.

Michaels writes:

The independent life begins with discovering what it means to live alongside the monoculture, given your particular circumstances, in your particular life and time, which will not be duplicated for anyone else. Out of your own struggle to live an independent life, a parallel structure may eventually be birthed. But the development and visibility of that parallel structure is not the goal — the goal is to live many stories, within a wider spectrum of human values.

There are numerous aspects of this dominant story — why we choose what we choose, how the media’s filter bubble shapes our worldview, why we love whom and how we love, how money came to rule the world — but Monoculture weaves these threads and many more into a single lucid narrative that is bound to first make you somewhat uncomfortable and insecure, then give you the kind of pause from which you can step back and move forward with greater autonomy, authenticity, and mindfulness.

The book’s epilogue captures Michaels’s central premise in the most poetic and beautiful way possible:

Once we’ve thrown off our habitual paths, we think all is lost; but it’s only here that the new and the good begins.

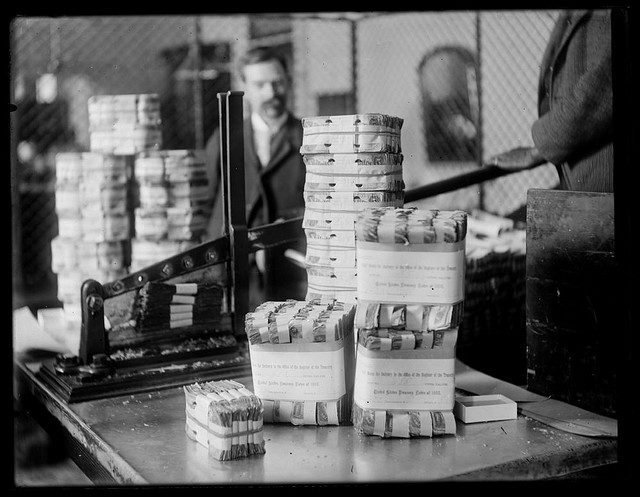

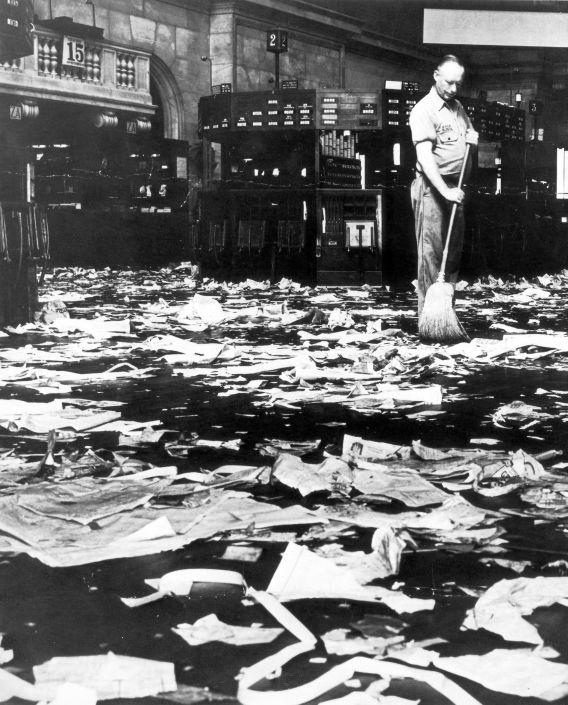

Public domain images via Flickr Commons