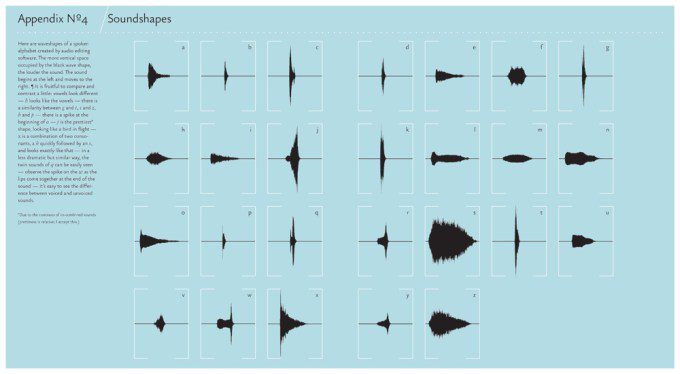

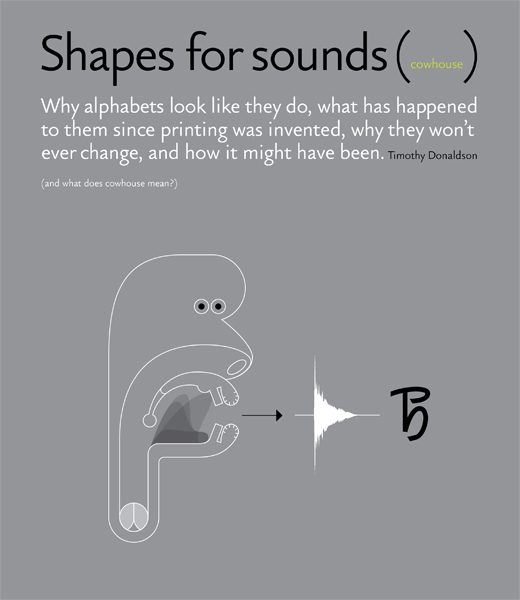

I’m endlessly fascinated by the intersection of sight and sound and have a well-documented alphabet book obsession. So I absolutely love Shapes for sounds (public library) by Timothy Donaldson, which explores one of the most fundamental creations of human communication, the alphabet, through a fascinating journey into “why alphabets look like they do, what has happened to them since printing was invented, why they won’t ever change, and how it might have been.”

I’m endlessly fascinated by the intersection of sight and sound and have a well-documented alphabet book obsession. So I absolutely love Shapes for sounds (public library) by Timothy Donaldson, which explores one of the most fundamental creations of human communication, the alphabet, through a fascinating journey into “why alphabets look like they do, what has happened to them since printing was invented, why they won’t ever change, and how it might have been.”

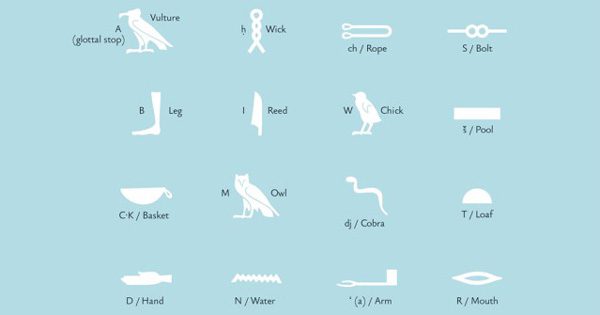

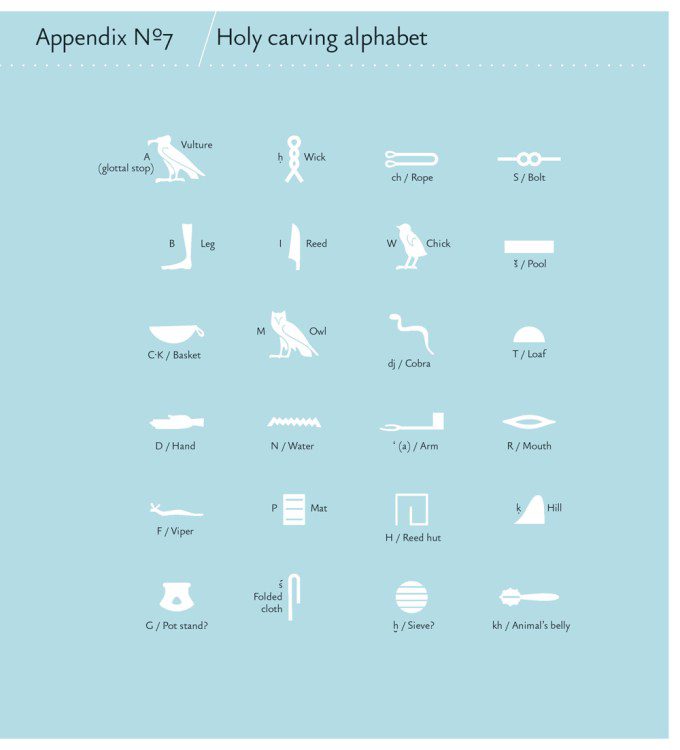

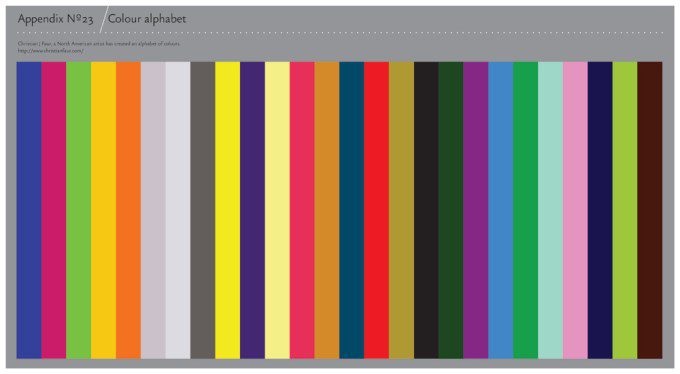

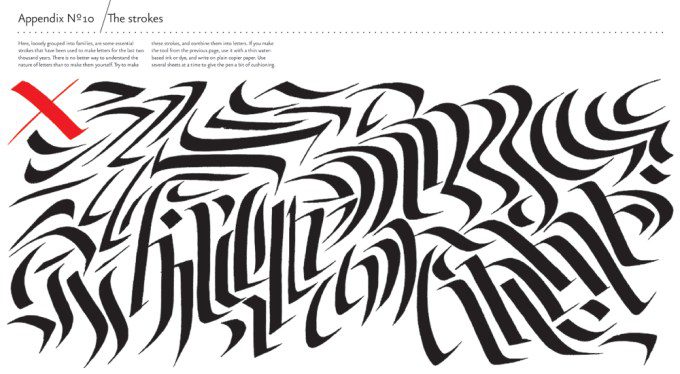

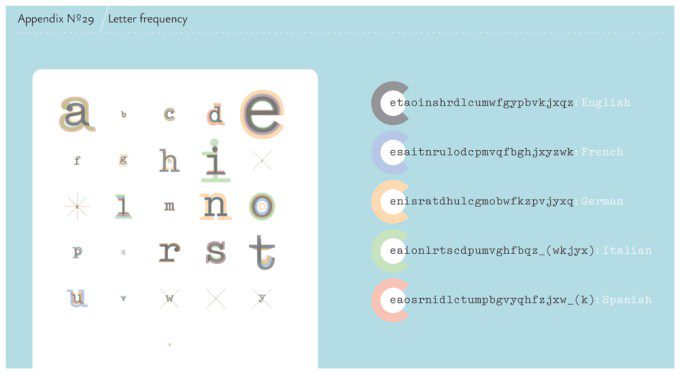

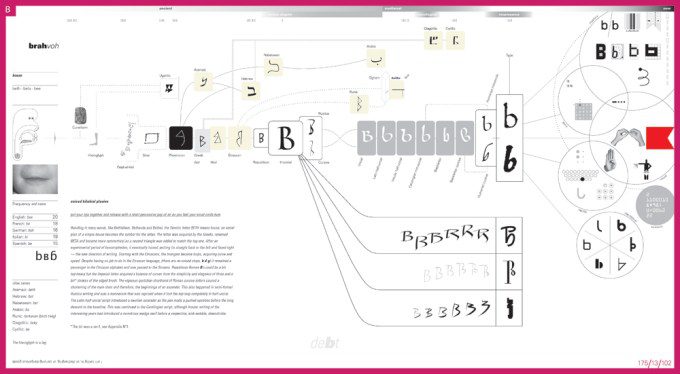

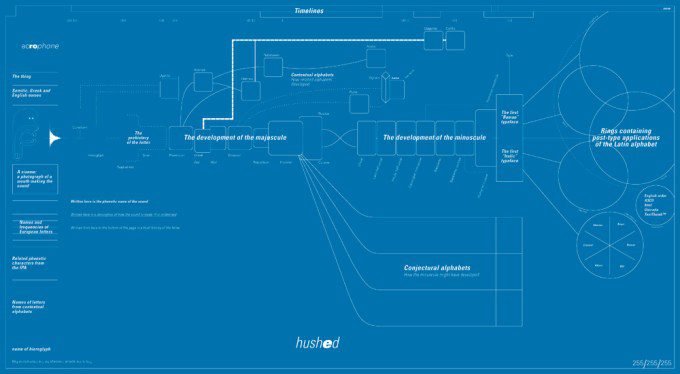

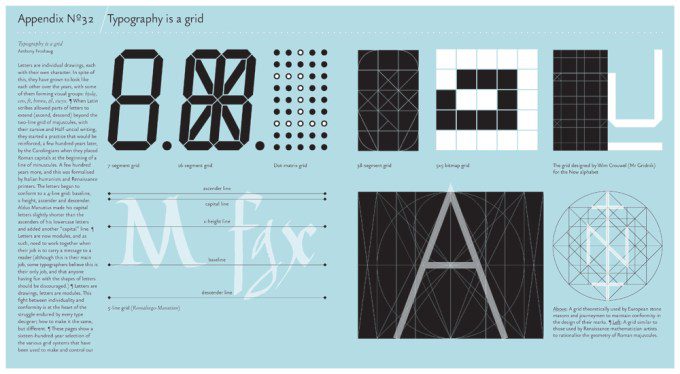

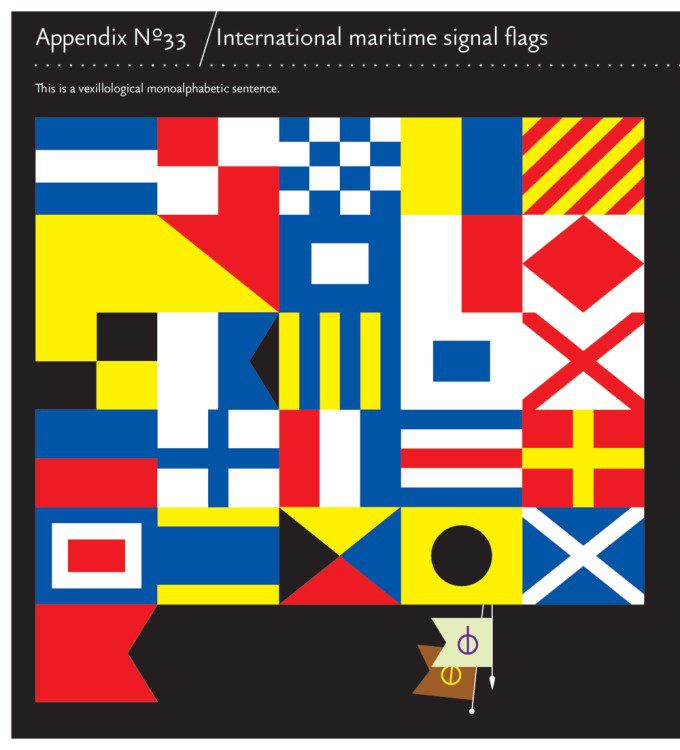

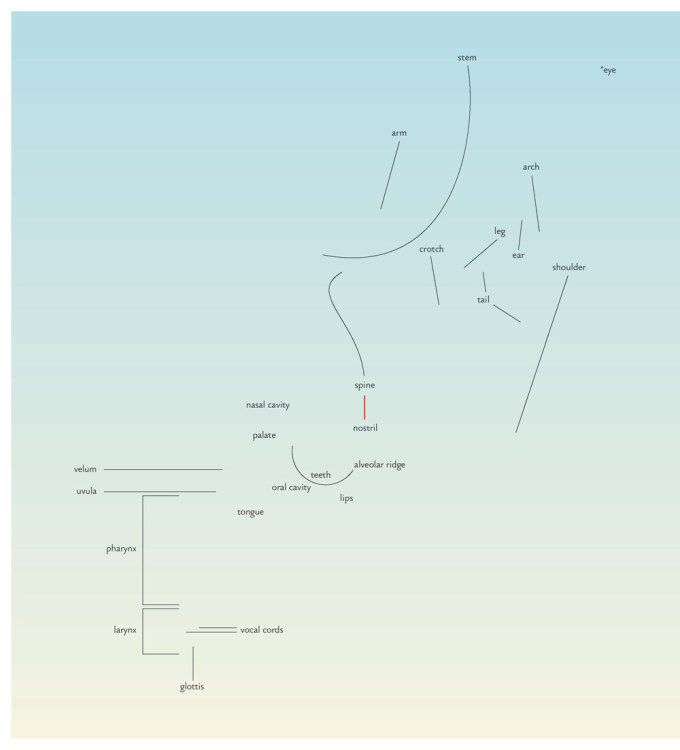

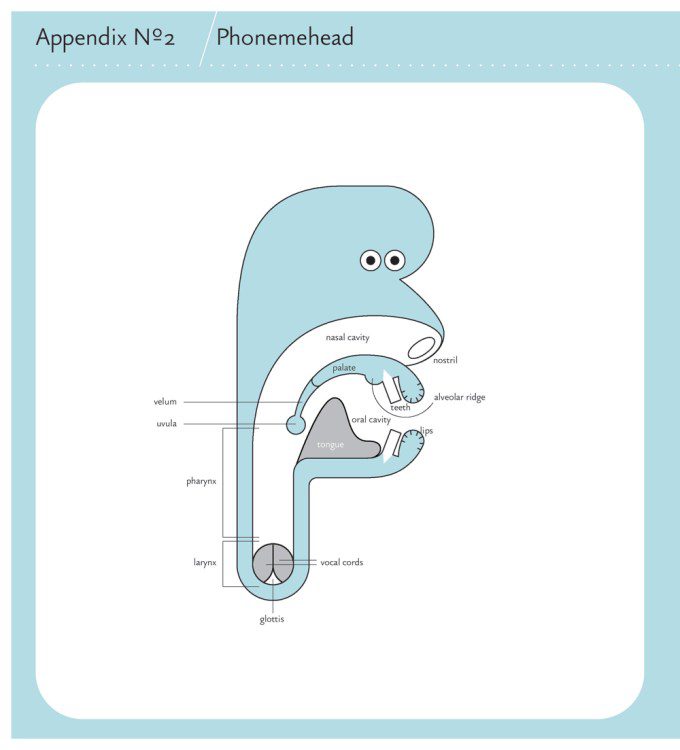

While the tome is full of beautiful, lavish illustrations and typography — like 26 gorgeous illustrated charts that trace the evolution of spoken languages into written alphabets — it’s no mere eye candy. Donaldson, a typographer, graphic designer and teacher, digs deep into the cultural anthropology of how letters were crystallized from sounds, scripts invented, words formed, and linguistic conventions indoctrinated.

Donaldson writes:

The alphabet is one of the greatest inventions; it has enabled the preservation and clear understanding of people’s thoughts, and it is simple to learn. It still has great significance; while the advent of type — printed alphabets — has curtailed any real development of the shapes of letters, the alphabet has been more greatly utilised in the last 500 years than ever before. Typography is the engine of graphic design, and writing is the fuel. But more than that, the alphabet has been the enabler of mass communication technologies from Morse code to the internet.

Though the Latin alphabet is the focal point, Donaldson explores an incredible range of related history, from ancient calligraphic traditions to semaphore, to bar codes and binary code, exposing the magnificent cross-pollination of disciplines — design, typography, anatomy, phonetics, sociology, linguistics, psychology and more — that gave birth to one of our civilization’s oldest and most powerful technologies.

Donaldson considers the elemental delight of graphics:

I would love to have the experience of having envelopes drop through my door with no address, just a picture of me and my house on the front. I would like to buy a newspaper full of nothing but pictures and graphic devices, and to find my way home using road signs that are just arrows and drawings, but I think these events a re a long way off. To cross national borders still requires a textual document; a passport is not just a picture of your face. The obligator tax-return, a document that, if ignore, will make you a criminal, contains no images. The highway code features many image-based signs, yet must be explained with words. The interent is 95% text.

Shapes for sounds comes as yet another gem from the fine folks at Mark Batty, my favorite indie publisher, who brought us such excellence as Notations 21, Cultural Connectives, Drawing Autism and more.