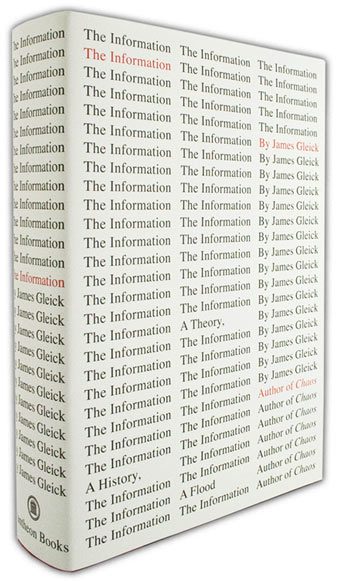

The future of information is something we’re deeply interested in, but no such intellectual exploit is complete without a full understanding of its past. That, in the context of so much more, is exactly what iconic science writer James Gleick explores in The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood — a new book that may just be the book to read this year, flowing from tonal languages to early communication technology to self-replicating memes to deliver an astonishing 360-degree view of the vast and opportune playground for us modern “creatures of the information,” to borrow vocabulary from Jorge Luis Borges’ much more dystopian take on information in the 1941 classic, “The Library of Babel,” which casts a library’s endless labyrinth of books and shelves as a metaphor for the universe.

The future of information is something we’re deeply interested in, but no such intellectual exploit is complete without a full understanding of its past. That, in the context of so much more, is exactly what iconic science writer James Gleick explores in The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood — a new book that may just be the book to read this year, flowing from tonal languages to early communication technology to self-replicating memes to deliver an astonishing 360-degree view of the vast and opportune playground for us modern “creatures of the information,” to borrow vocabulary from Jorge Luis Borges’ much more dystopian take on information in the 1941 classic, “The Library of Babel,” which casts a library’s endless labyrinth of books and shelves as a metaphor for the universe.

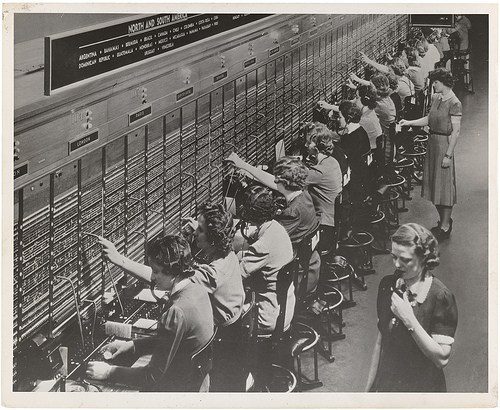

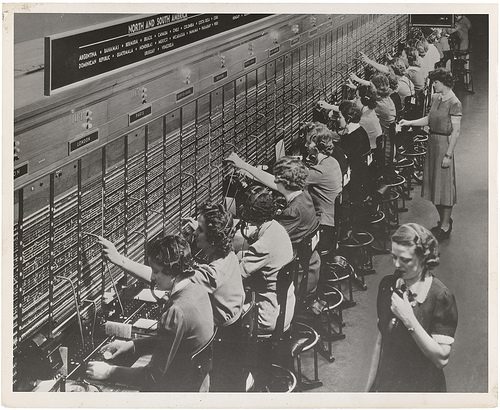

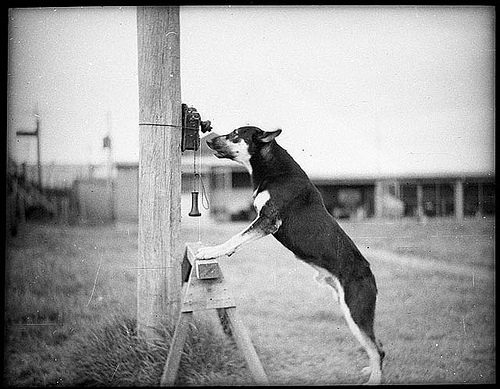

Gleick illustrates the central dogma of information theory through a riveting journey across African drum languages, the story of the Morse code, the history of the French optical telegraph, and a number of other fascinating facets of humanity’s infinite quest to transmit what matters with ever-greater efficiency.

Gleick writes:

We know about streaming information, parsing it, sorting it, matching it, and filtering it. Our furniture includes iPods and plasma screens, our skills include texting and Googling, we are endowed, we are expert, so we see information in the foreground. But it has always been there.

But what makes the book most compelling to us is that, unlike some of his more defeatist contemporaries, Gleick roots his core argument in a certain faith in humanity, in our moral and intellectual capacity for elevation, making the evolution and flood of information an occasion to celebrate new opportunities and expand our limits, rather than to despair and disengage.

Gleick concludes The Information with Borges’ classic portrait of the human condition:

We walk the corridors, searching the shelves and rearranging them, looking for lines of meaning amid leagues of cacophony and incoherence, reading the history of the past and of the future, collecting our thoughts and collecting the thoughts of others, and every so often glimpsing mirrors, in which we may recognize creatures of the information.

For a closer look at The Information, see Freeman Dyson’s fantastic New York Review of Books essay, How We Know, and this excellent interview with Gleick.