The Works Progress Administration was a controversial New Deal government agency created by President Roosevelt in 1935 as an answer to the Great Depression. Although considered by some near-communist in nature, the WPA generated a staggering number of public artifacts and initiatives in its eight-year run — roads, buildings, parks, bridges, libraries, schools, housing programs, food redistribution efforts. Investing nearly $7 billion in these projects and providing some 8 million jobs, the WPA became the largest employer in the country, offering the most competitive hourly wages within its areas of employment. Among its claims to fame are iconic landmarks like the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, the iconic mural at West Point military academy, Maryland’s Camp David, and New York’s LaGuardia Airport.

But one of the greatest contributions the project made to contemporary culture comes from its visual heritage. The WPA funded the Federal Arts Program — a large arts, drama, and media project that had two central goals: To create artwork for non-federal public buildings, and to provide jobs for unemployed artists. And it did both — it employed thousands of artists, actors and musicians, which resulted in 17,744 sculptures, 108,099 easel paintings, 2,566 murals and 240,000 prints.

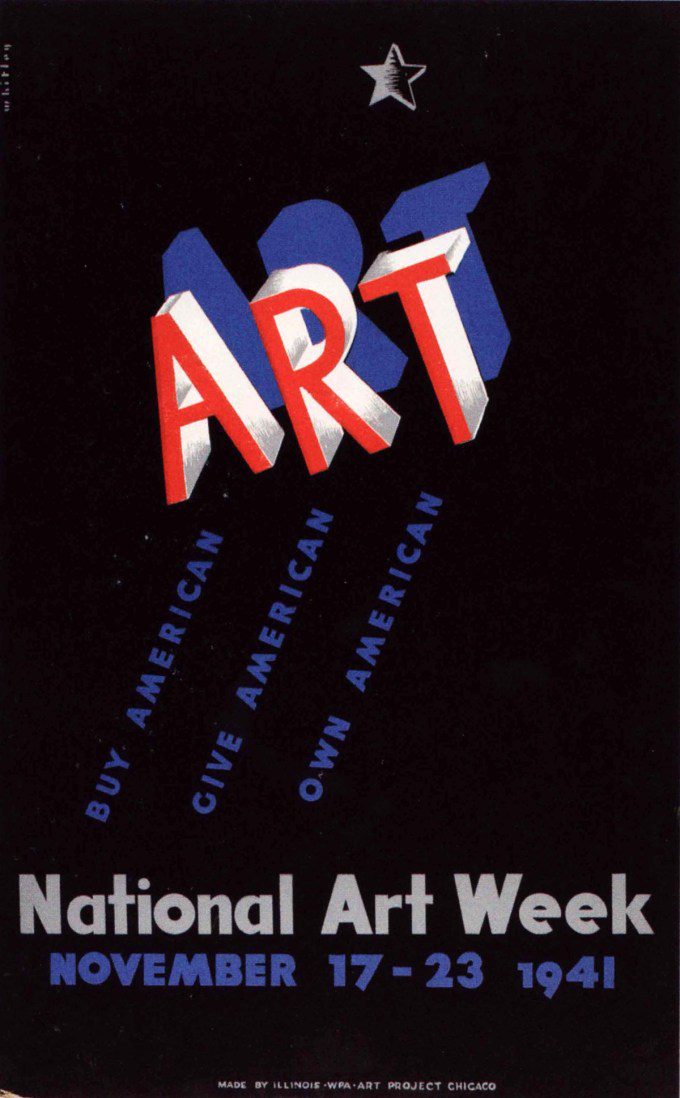

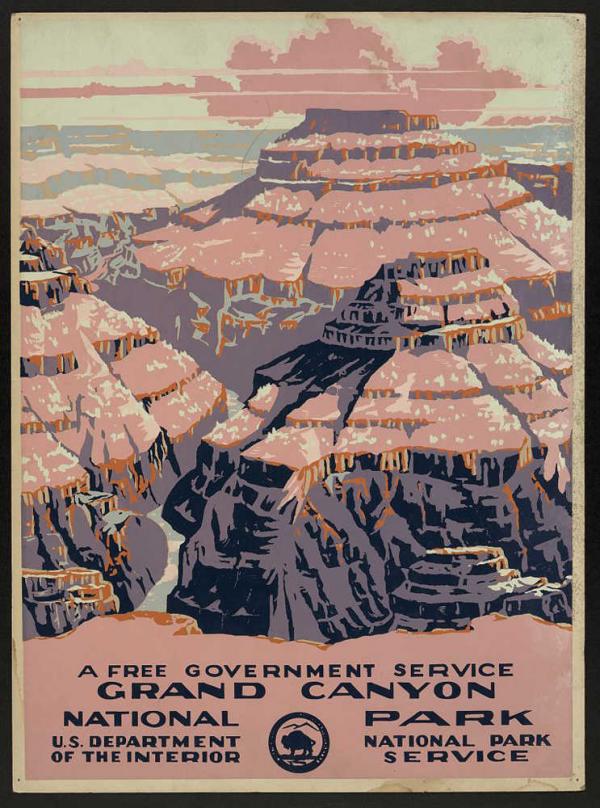

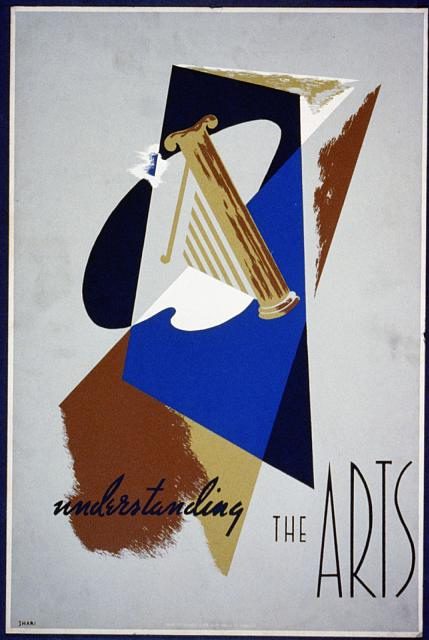

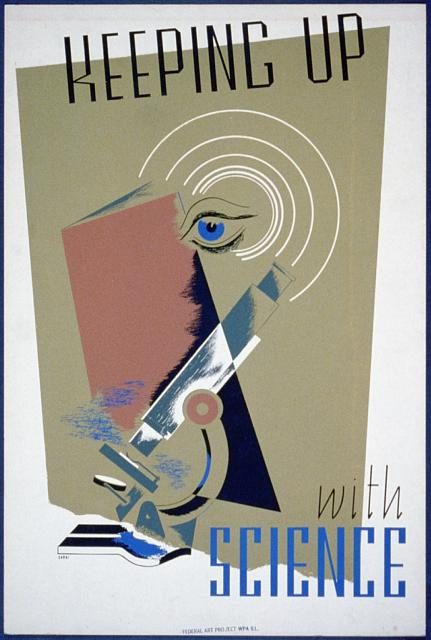

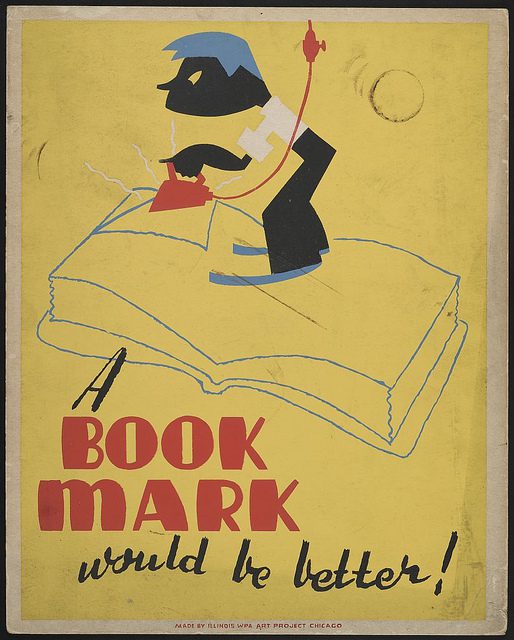

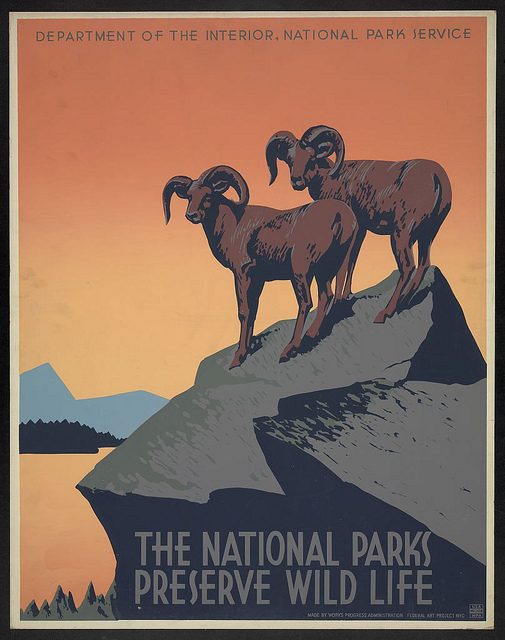

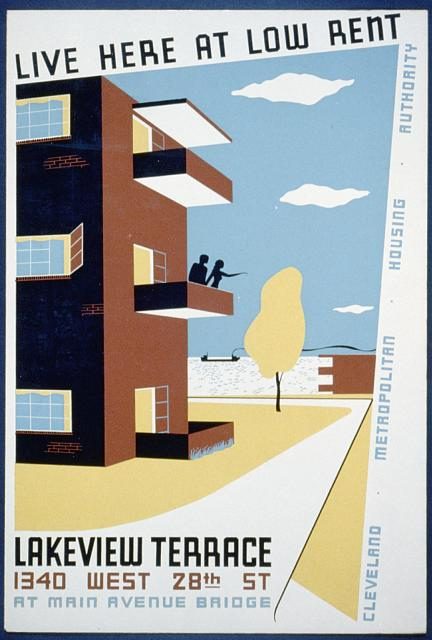

These artworks were incredibly influential in shaping the visual language of that era and eras to come — particularly the remarkably rich WPA silkscreen, lithograph, and woodcut posters designed to promote anything from public health and safety programs to art exhibitions to travel and tourism, the best of which are collected in Posters for the People: Art of the WPA (public library).

Today, only 2,000 of these posters remain in existence and the Library of Congress has the largest singular collection, featuring about 900 of them, brimming with the bold typography, vibrant color palettes and rich art direction of mid-century aesthetic sensibility.

But for all the virtues of liberalizing, democratizing. and de-institutionalizing the arts, one has to wonder whether a centralized effort to employ artists and creators in the economic recovery process may have some merit, if only for the sake of fostering widespread visual literacy and establishing the aesthetic legacy of the era. How might today’s world be different if our political leaders considered investing in such art-driven efforts the way the WPA did? Adjusted for inflation, the WPA’s $7 billion would equal roughly $160 billion in today’s money — how does that compare to what today’s government is investing in war?