The late and exceedingly great Roger Corman died on Thursday at the age of 98. In his lifetime he produced hundreds of movies, and in the process launched the careers of many of our most beloved filmmakers. Martin Scorsese (“Boxcar Bertha”), Francis Ford Coppola (“Dementia 13”), Peter Bogdanovich (“Targets”), Jonathan Demme (“Caged Heat”), and many, many more had their early breaks at Corman’s production companies. He also distributed classic films by Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini and Akira Kurosawa when he wasn’t producing independent genre flicks that would make bizarre double features with those dignified art house award-winners.

Roger Corman has always received credit for shepherding a lot of great directors, and for good reason. But there’s one director who rarely turns up on the list of iconic Roger Corman filmmakers … and that’s Corman himself.

It’s strange that Corman’s directing career could get so overshadowed, but not entirely surprising. Although he sat right behind the camera for 56 films (sometimes uncredited), he hadn’t made a film of his own since 1990’s “Frankenstein Unbound,” starring John Hurt, Raul Julia and Michael Hutchence from INXS. In the nearly 35 years since, Corman produced as many films as ever — which is to say, a mind-boggling amount — and he made many public appearances to promote those projects. To multiple generations of movie lovers he was a B-movie producer and a lovable spokesman.

And yet for almost 20 years, Corman was one of the most prolific directors working in show business. His career kicked off in 1955 with the western “Five Guns West.” And also the western “Apache Woman.” And also the post-apocalyptic “Day the World Ended.” And also some of the monster flick “The Beast With a Million Eyes.” It was his first year behind the camera and Roger Corman had already cemented his signature style: He worked cheap, he worked fast, he worked in whatever genre made money, and if the movie was good then all the better.

Many of Corman’s early, inexpensive, populist films became fodder, decades later, for ironic appreciation. You’ll find episodes of “Mystery Science Theater 3000” dedicated to merciless riffs on Corman’s “Swamp Diamonds,” “Gunslinger,” “It Conquered the World,” “Teenage Cave Man” and the melodramatically-titled “The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent.” And they’re all very funny, but if that’s all you knew of Roger Corman’s career, and if you weren’t paying attention to the movies playing behind the silhouettes of Joel Hodgson and his lovable ‘bots, you might think that Corman exclusively made stinkers.

But setting his (obviously low) budgets aside, Corman’s early run-and-gun directing approach — with an emphasis on genre films, catering to a burgeoning post-war teen drive-in audience — gave him a lot of freedom. A handful of exploitation elements could bring in the bucks, and in the process he often snuck in thoughtful, in your face commentary.

“Teenage Cave Man,” features a 26-year-old Robert Vaughn (who appeared older), the story of a caveman who challenges the conservative social structures of his elders, goes into forbidden territory to find monsters, and, in a surprising twist, reveals that the film is set in the distant future, after a nuclear holocaust. It’s a story that could have been a classic episode of “Twilight Zone,” just a bit larger, and with sillier creatures.

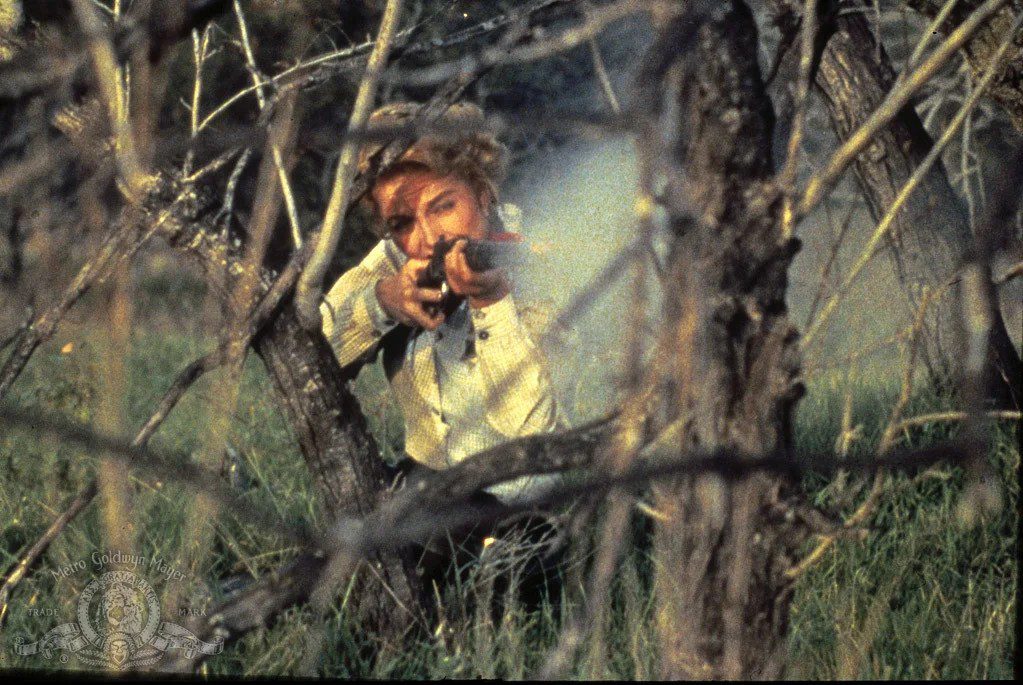

Many of Corman’s early films starred the talented Beverly Garland, whose strong performances improved even his least polished material. She deserved more success, but Corman allowed her to truly shine. Their feminist western “Gunslinger” stars Garland as a sheriff’s wife who takes on the badge after her husband is killed and battles against a corrupt saloon owner, played by Allison Hayes. The town is controlled by two women, filled with ineffective men, and visited by a vengeful Civil War vet who becomes entangled in a love triangle between the heroine and villain, both of whom pursue careers often denied to women in the old west, as well as in Hollywood.

It was sincere, progressive, and angry filmmaking, much like his monster classic “The Wasp Woman,” featuring the talented Susan Cabot as a model who becomes a cosmetics tycoon. Her need to remain relevant in a youth-driven economy — in an industry dominated by patronizing male underlings who don’t respect her — leads her to become, as one might imagine, a “wasp woman.” It’s a timeless story of arrogance and horror, akin to the iconic Universal Monster movies and superior to at least a few of them (the original “Mummy” sequels, at the very least).

The advantage of producing many movies quickly is that you become better at it, and you improve rapidly. By the time the 1960s arrived, Corman had found his stride. His first Edgar Allan Poe adaptation, “House of Usher,” was such a success that it launched a loosely connected series. Corman and Vincent Price worked together on eight Edgar Allan Poe movies, though the 1963 shocker “The Haunted Palace” was an adaptation in name only, instead borrowing the plot from H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” and hoping nobody would notice.

Not all the Corman/Price movies were equally good, but most are enchanting. “The Haunted Palace” is a wonderfully gothic and twisted story of multigenerational terror, regardless of its misleading literary origins. “The Pit and the Pendulum” is a wonderfully eerie adaptation, reminiscent of the darkest and most lurid E.C. horror comics of the 1950s. The image of Price operating the title death machine is seared into the minds of every Poe fan, every Corman fan, and every Price fan (and that should just about cover us all).

Everyone has their favorites (and more people should include the underappreciated “Tomb of Ligeia” among them) but the greatest film in Corman’s Poe series is almost certainly “The Masque of the Red Death.” Price plays Prospero, a sly hedonist who has walled off the rich and unscrupulous while a deadly plague ravages the country. They get their just desserts in the end. The story is as relevant as ever, Price was rarely better, and the cinematography by Nicholas Roeg — who would later direct classic films like “Don’t Look Now” and “The Man Who Fell to Earth” — is so stunningly vibrant it pierces your eyes and threatens to permanently stain the screen.

Corman did not always conceal his social commentary behind audience-friendly stories of sex and violence. Sometimes he took a more direct approach. He cast William Shatner in “The Intruder” as a detestable plotter who drives a small town into a shocking racist rage in response to school integration. As the 1960s continued, Corman directed several counterculture freakout films like “The Trip,” written by Jack Nicholson and starring Peter Fonda as a man who takes acid for the first time, leading him on an unusual journey of self-discovery. Equally strange is “Gas! -Or- It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It.”, a loosely structured but intriguing sci-fi comedy in which a deadly gas wipes out everyone over 25, and the rebellious youths struggle to create a future without repeating the old mistakes, simultaneously rejecting and romanticizing society’s past.

Roger Corman's extensive directorial career can be best described by its lack of fixed style. Corman followed the trends of popular culture, making westerns during their peak, monster movies when they drew large audiences, politically charged films for young viewers during times of mobilization, and classic horror and crime stories in between. His films made money, attracted an audience, and challenged the conventional idea of “good” cinema.

Despite being able to handle high-quality production when necessary, Roger Corman faced challenges due to tight schedules and limited budgets, creating art for the general public. Sometimes this resulted in exceptional art, while other times it was simply good, traditional American schlock.