More than 500 million years ago, the deep, dark ocean was illuminated by the strange light of glowing corals, according to new genetic and fossil analyses. The findings extend the beginnings of bioluminescence by almost 300 million years, researchers report on April 24 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“Our study provides the oldest known evidence for the emergence of bioluminescence on Earth, and more than doubles the previous record for when bioluminescence first emerged,” says Danielle DeLeo, an integrative biologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The previous record, reported in 2022, was set by the 267-million-year-old ancestor of sea fireflies — small, seed-shaped crustaceans.

The ability to produce light has evolved at least 100 times across the tree of life, in everything from fishes to corals to fungi (SN: 4/27/17). Chemical reactions generate the light, which can help the organisms hunt prey, attract mates or even hide from predators (SN: 6/7/16).

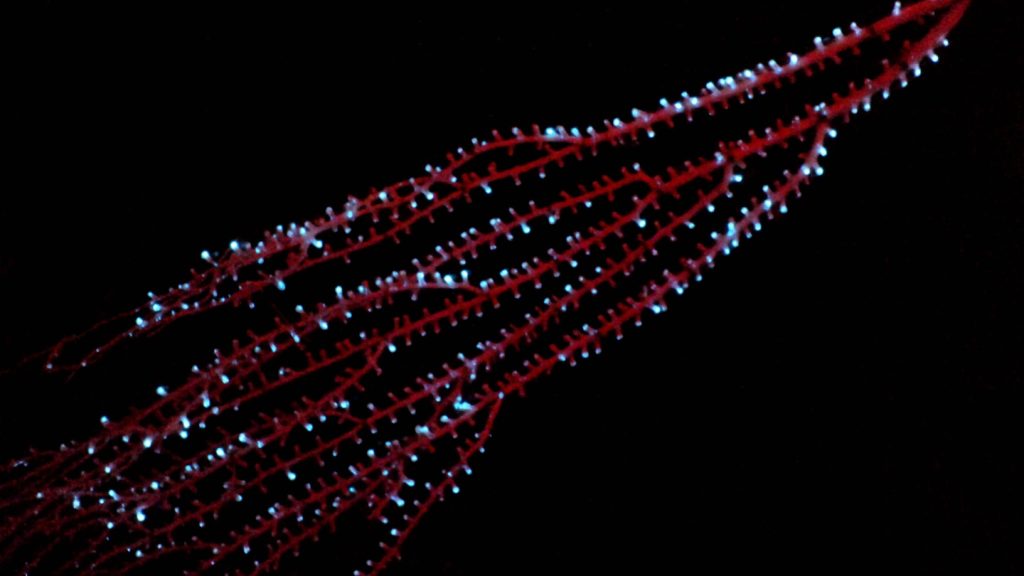

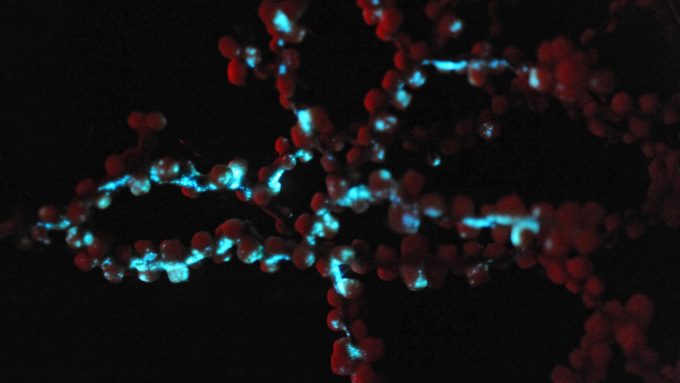

DeLeo and colleagues aimed to understand how the trait developed in a coral subgroup known as octocorals. These species — including soft corals, sea pens and sea fans — often live in the deep sea, have 8-fold symmetry and many are luminous.

Examining the DNA of 185 octocoral species revealed genetic similarities that the team used to create an evolutionary tree, showing how the species are related to one another. Researchers then used octocoral fossils to estimate when lineages split into separate branches. Finally, based on when glowing species evolved and where in the tree they reside, the team calculated the probability of coral ancestors being bioluminescent.

“It turns out the ancestor to all octocorals was bioluminescent,” DeLeo says. That ancestral species lived roughly 540 million years ago, the team calculates.

Octocorals’ bioluminescence is surprisingly old given the trait’s evolutionary volatility, says Todd Oakley, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who led the 2022 sea fireflies study. “It seems to originate pretty easily, and it seems to be lost pretty easily.”

Evolutionary biologist Jessica Goodheart of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City wants to know if the evolution of bioluminescence had a role in driving the diversification of octocorals as a group.

DeLeo says bioluminescence may have originated as a result of other, more ancient cellular chemical reactions. These reactions could have been retained because they were co-opted into signaling and communication, providing animals with an advantage.

It’s possible that other, more ancient bioluminescent organisms — such as bacteria, algae and comb jellies — could have evolved their glow even earlier than octocorals. But, DeLeo says, limitations in the fossil record make it challenging to date when bioluminescence first arose in those groups.