OOn July 6, 1901, Natalie Karsakoff took a break from her busy schedule to pen a letter to her mentor, the French botanist Édouard Bornet. Hoping he would join her on the northwest coast of France, she couldn’t help but boast a bit about where she was staying: the home of her good friend Anna Vickers.

Their place had everything a summer vacationer needed, she wrote: “a magnificent laboratory, well-lit, clean,” with “a stove to warm one's feet,” “blinds to filter the light,” and, of course, “tiled floor that could handle any liquid.” Right outside was the main attraction: a shore populated with what would eventually prove to be hundreds of species of algae, swaying underwater and waiting to be discovered.

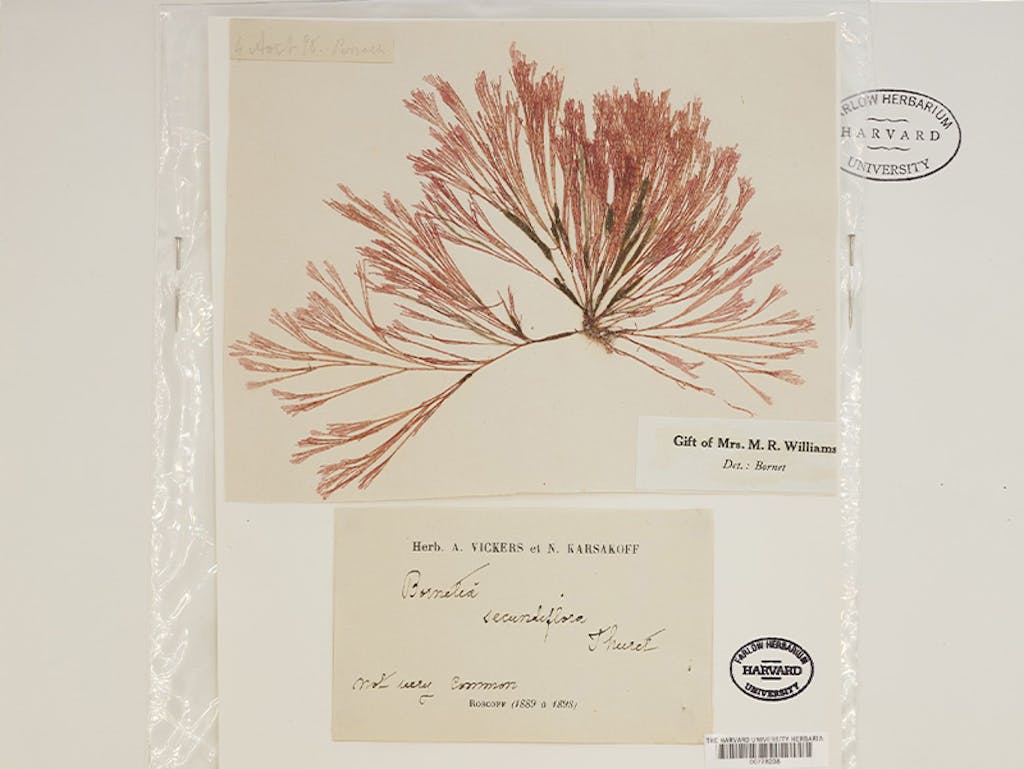

Karsakoff and Vickers, whose story is outlined in a intriguing paper by science historian Emily S. Hutcheson, were dedicated algologists. For 12 summers, from 1889 to 1901, they lived together at Vickers’ house in Roscoff, France, “revel[ing] among Chylocladias, Myrrotrichias, Callophyllis, Callithamnions, and Polysiphonias,” as Karsakoff wrote in another letter. They pushed the unlikely tradition of female seaweed experts to new levels. And they did all this within a stone’s throw of the Station Biologique De Roscoff, a research institute where other marine enthusiasts, mostly men, pursued similar interests in very different ways.

The Seaweed Craze

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, a fervor for natural history swept Europe. In Victorian England especially, this general enthusiasm peaked into fads, often centered around collecting and arranging specimens, and enabled by changes in infrastructure and technology and increasing democratization of science. As historian Stephen Hunt told Atlas Obscura, working-class people and aristocrats alike used their expanding leisure time to hop trains out to the seashore or countryside, gather specimens, and examine them under increasingly affordable microscopes or present them at the next meeting of their local natural history club.

Their lodging had everything a summer vacationer needed: a magnificent laboratory …

One of these trends was the “seaweed craze.” According to the historian David Elliston Allen, European algae mania began in London in the 1750s when a merchant and botanist named John Ellis created a fanciful miniature seascape out of frondy specimens that ended up impressing the Princess Dowager of Wales. Within a century, the United Kingdom’s shorelines were thronged with excited splashers wielding, in the words of famed 19th-century seaweeder and author Margaret Gatty, “a basket, a bottle, a stick, [and] a strong pair of boots.”

Women were in on it from the beginning. (Ellis got his specimens from his sister in Dublin—behind every great man is a woman sending him seaweed in the mail.) But over time, sea plants emerged as a unique locus of opportunity for female natural historians, who were barred from major scientific societies and discouraged from supposedly unseemly pursuits like chasing animals and dissecting the sex organs of land plants. Plus, many were at the shore already, attempting to restore their health through sand promenades and breathing salty air.

Women who got interested in collecting seaweed tried to encourage other women to join in. Gatty—who started in East Sussex after her seventh childbirth—used much of her 1872 book British Sea Weeds to address what she calls her “sisterhood,” hoping to bring them out to the tide and give them the chance to see and feel what she had. She offered fashion advice (“let woolen be in the ascendant as much as possible; and let the skirts never come below the ankle”) and, perhaps more importantly, a pep talk. “You are in the right dress at the right place,” she wrote, “… free, bold, joyous, monarch of all you survey, unhindered, at ease, at home! At home, though among all manner of strange, unknown creatures, thrown at your feet every minute by the quickly succeeding waves.”

Soon, a kind of subculture emerged. Some women collected with their husbands (one male naturalist wrote about how his wife used a “larger muff than the present fashion would recommend” to smuggle their seaweeding equipment offshore). Others worked with male scientists, who included their samples in published work. Still others concentrated on creating public-facing natural history works, or incredible aesthetic objects—including the first book ever illustrated with photographic images, Anna Atkins’s 1843 Photographs of British Algae, and colorful scrapbook albums of real specimens that are still collected and used in scientific research today.

The Central Bureau

Across the channel in Roscoff, and decades after some of their predecessors, Karsakoff and Vickers delved into algology from a slightly different perspective. Karsakoff, who was born in Russia and educated in France, had formal scientific training from the Sorbonne and experience working at Moscow State University. Although Vickers didn’t have this training, family wealth had provided her with other opportunities—to “study botany through collecting” while traveling, and to buy an oceanfront house in Roscoff and equip it with lab space and supplies, Hutcheson writes. They had the support of male mentors like Bornet and less worry about, as Karsakoff put it, “[running] about the beach and among the rocks dressed as a guy.” Neither was married.

They also had different goals for their work than some of the women who came before. Instead of making scrapbooks or public guides, the two spent their summers working on scientific papers and putting together a florule: a Who’s Who of seaweeds and other algae growing in this hyperdiverse portion of shoreline.

But as Hutcheson argues in her account, these scientifically ambitious women shared something in common with Gatty’s seaweed sisterhood. They thrived in, and needed, community. When Karsakoff first arrived in Roscoff in 1889, she was fascinated by the existence of the Station Biologique, but intimidated by its formality. Even if she had wanted to study or work there, it would have been difficult. Lodging was only offered to men.

They “interpreted the natural world as a place of mutual support.”

Karsakoff and Vickers met when she first visited, and connected over their shared love of algae. That summer, Karsakoff began working with Vickers and staying in her home. Decades before Virginia Woolf published “A Room of One’s Own,” Vickers gave Karsakoff “not only a beautiful bedroom but a cabinet de travail or laboratory all to yourself,” Karsakoff wrote.

They also experienced something more: “the joy of being crazy as a pack of March hares” while combing the beach, wrote Karsakoff, with “devoted friends to help in the spreading and drying so as to enable you to look at the microscope and enjoy yourself.” Over the course of their dozen summers, the two invited other women with similar interests to join them (sometimes along with their mothers, who served as chaperones).

During the rest of the year, if they traveled to other shores, they tried to arrange meetups: Everything always went better with “two people mad together over the dredging, drying, etc.” as Karsakoff wrote to another algal enthusiast in 1897, trying to convince her to join Vickers in Naples. Eventually, the pair’s commitment to building up these networks made Karsakoff feel as though she, herself, was “gradually becoming a central bureau in feminine algology.”

Symbiosis

This way of working gave Vickers and Karsakoff a different perspective of their subject matter—from the seaweeding women who came before, but also from the mostly male scientists working nearby at the Station Biologique, Hutcheson notes. While the station focused on lab work and individual specimens, the women’s florule sought to place every species properly in its environment and to understand where different marine plants grew and thrived, whether atop exposed rocks or deep beneath the waves.

Though noting which species could be found where had always been important to collectors, the idea that this had biological importance was just beginning to gain traction. And while that era’s mainstream theories focused on violence and competition between species, Karsakoff and Vickers “interpreted the natural world as a place of mutual support,” Hutcheson writes, like the working and living spaces they had built.

According to Hutcheson this is most noticeable in a paper Karsakoff published in 1892, describing the lives of small, fluffy brown algae in the genus Myriotrichia. Members of Myriotrichia grow epiphytically, perched on top of other underwater plants. At the time, close associations between species were often seen as competitive, if not outright parasitic. But Karsakoff describes the algae as harmless tufts, which simply “take their share of heat and sunlight” without harming their hosts—just as she herself enjoyed the warmth of Vickers’ foot stove, and the sunlight filtering through the laboratory blinds. Today, mutualistic relationships like the one Karsakoff recognized are seen as main components of the ecosystems they are a part of.

Even after many years of effort, Vickers and Karsakoff could never publish their florule themselves. Vickers passed away suddenly in 1906 at the age of 54, leaving collections from a trip to Barbados, which were eventually published by other female collaborators. In 1954, the Roscoff research of her and Karsakoff was included in a larger species inventory conducted by the Station Biologique, where some of their specimens are still kept. Others are in the Farlow Herbarium at Harvard University. Farlow Herbarium.

However, the most notable example of their working relationship doesn’t come from Roscoff. In 1896, Karsakoff described and named a new genus of algae that Vickers had discovered in the Canary Islands, which a paper she detailed in Annales des Sciences Naturelles. In the illustration that accompanied the paper image, the algae, branched and overlapping and filamentous, spreads like an umbrella above Karsakoff’s name and the name she gave the species: Vickersia canariensis.

Lead image: Biodiversity Heritage Library