At its best, a close relationship is a partnership of mutual nourishment — a portable ecosystem of interdependent growth, supported by a network of trust and tenderness. It profoundly changes a person and yet helps them become more authentic as assumptions give way to presence and issues are transformed into open connections.

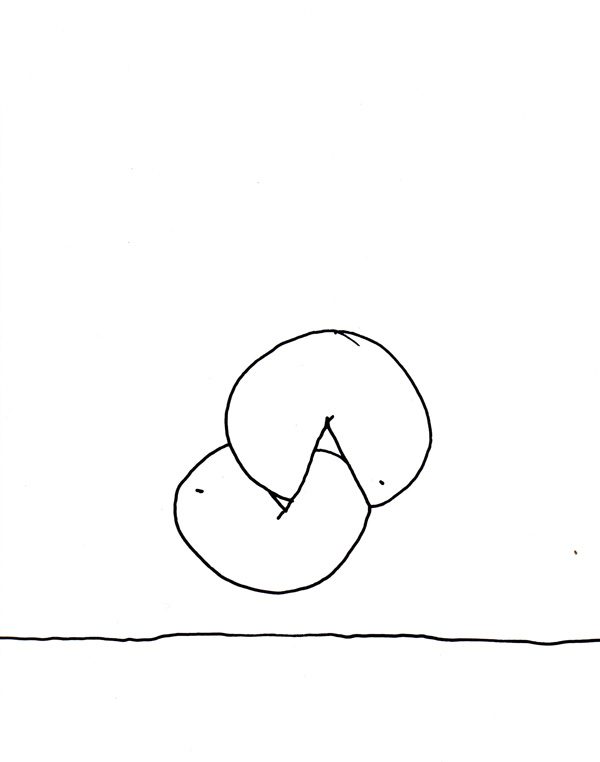

In his slim and remarkable book Twice Alive (public library), poet, geologist, and translator Forrest Gander uses inspiration from the natural world to create a poetic “ecology of intimacies,” honoring lichens’ “extreme frugality in drought” and the “long soft sarongs of moss” as a means “to rediscover the essence of life itself.”

An era after Beatrix Potter discovered how lichens reproduce — asexually, spreading living matter from both partners to inhabit a new environment — Gander ponders the “theoretical immortality” of such reproduction and reflects:

The thought of two things that merge, mutually altering each other, two things that, intermingled and interactive, become one thing that does not age, brings me to think of the nature of intimacy. Isn’t it often in our most intimate relations that we come to realize that our identity, all identity, is combinatory?

I think of Einstein, who viewed “combinatory play” as the core of creativity; I think of how love may be the ultimate creative act, the way it reshapes the self and the space between selves.

In one of the love poems at the heart of the books, Gander considers how in such fusion of intimacy the partners are “not fused, not bonded, but nested.” Echoing the challenging question Mary McCarthy posed to Hannah Arendt — What’s the use of falling in love if you both remain inertly as-you-were? — he writes:

The reconfiguration is instantaneous

experience. It is being

itself. But whose being now? Was I

endowed with some special pliability so

that becoming part of you I didn’t pass

through my own nihilation? And what

does the death of who-you-were mean to me

except that now you are present, constantly.[…]

Without you I survived and with you

I live again in a radical augmentation

of identity because we have

effaced our outer limits, because

we summoned each other. In you,

I cast my life beyond itself.

This radical expansion of the self is indeed the great reward of intimacy, not only between people but also in an ecological sense — how organisms interweave with each other to become a system of interdependence greater and more fully alive than its parts, how understanding this new way of being calls for a new way of perceiving. Gander writes in another poem:

To see what’s there and not already

patterned by familiarity — for an unpredicted

whole is there, casting a pair of shadows, manipulating

its material, advancing, assembling enough

kinship that we call it life, our life, what

is already many lives, the dimensions of

its magnitude veiled to us as we live it —

Complement with Ursula K. Le Guin’s poem “Kinship” and Shel Silverstein’s timeless illustrated story about the secret to nurturing relationships, then revisit this meditation on lichens and the meaning of life.