HHumans are venturing into space more and more: NASA's Artemis program aims to send astronauts back to the moon and establish a permanent orbiting lab in the next few years, and private companies like Blue Origin and Space X plan to take tourists beyond Earth for a fee.

And where humans go, so does human conflict. Zackery Kowalske, a Ph.D. researcher with Staffordshire University in the UK, who is finishing his doctoral research on the environmental impact on bloodstain pattern analysis and works as a full-time crime scene investigator in Georgia, expressed that as we become more of a spacefaring species, there will be space detectives who investigate crimes.

Kowalske examines how blood splatters differently on concrete, snow, and sand. However, as a self-proclaimed "huge space nerd," he began pondering how gravity—or the lack of it—might affect blood splatter.

He conducted a review of any space-related blood research and eventually connected with George Pantalos, a cardiovascular physiologist at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, who studies surgery in space, including blood in space.

Kowalske and Pantalos met in person for coffee, off an interstate, when Pantalos was on his way to Florida for a zero-gravity flight campaign on a plane that flies parabolas to simulate the gravity of space flight. "Zack proposed an unusual experiment," Pantalos remembers. "But I enjoy unusual experiments because they can be fun. The most outlandish ones are often the most educational and force you to think differently. So I was intrigued."

Pantalos has taken part in 62 zero-gravity flights. Kowalske wanted him to perform an experiment on one of them: record in high-definition the splatter of blood from a syringe onto a paper target, which he could compare with the same experiment in normal gravity in his lab.

Pantalos knew that these flights often had extra time built in—extra parabolas flown, in case a particular experiment failed. He informed Kowalske that the next potential flight—aboard a modified Boeing 727 parabolic aircraft nicknamed the "Vomit Comet"—was in six months, in May of 2022. He pledged to bring the materials for the experiment with him, including synthetic blood made of 40 percent glycerin and 60 percent red food coloring (as real blood would contaminate the plane) and do his best.

There will be space detectives who investigate crimes.

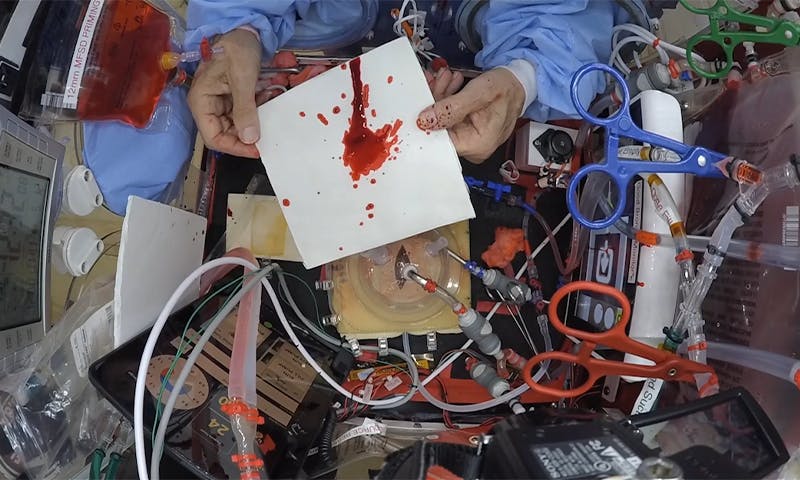

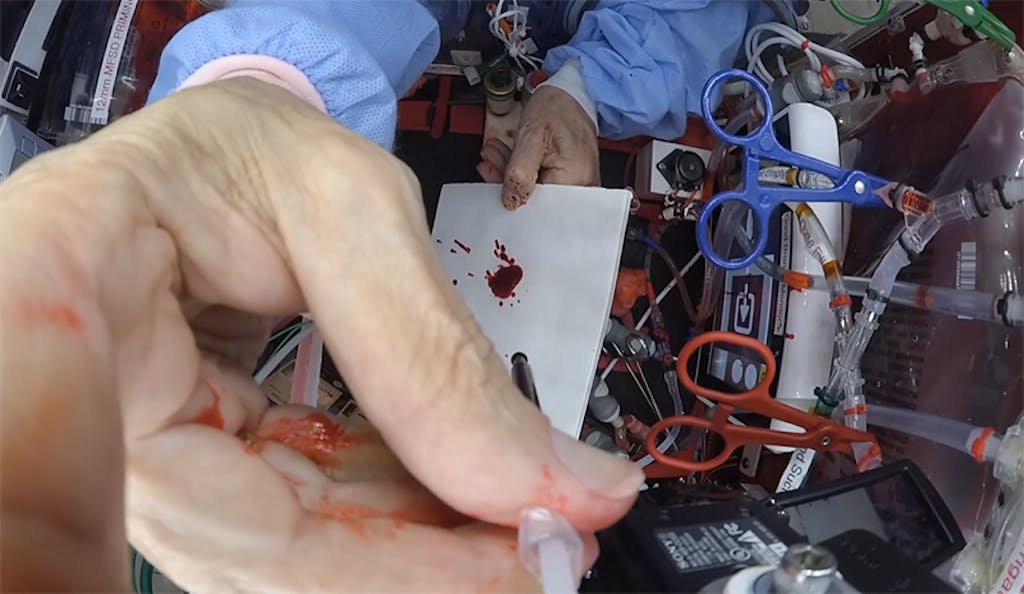

As it turned out, they were fortunate, and there was indeed extra time on the next flight, so Pantalos was able to carry out the experiment. With the cameras recording, he squirted the synthetic blood into the air 20 centimeters from the paper targets and captured the splatter inside a repurposed pediatric incubation chamber, called a glove box.

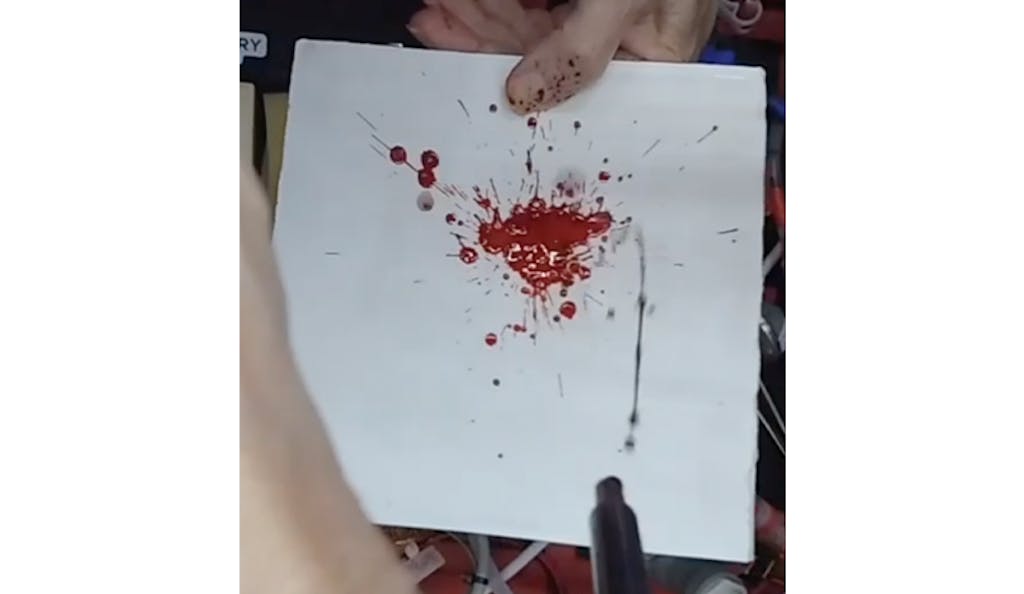

The results of that experiment are in a new paper, released this month in the journal Forensic Science International: Reports. Kowalske and Pantalos, along with colleagues from Staffordshire University and University of Hull, found that liquids similar to blood behave differently under space conditions. Like blood, the blood substitute is more likely to adhere to surfaces and travel in a straight line in space, rather than a parabolic path.

They also discovered that the force of surface tension of blood-like liquids is much higher in zero gravity, which surprised Kowalske. Surface tension, the cohesion of molecules in a liquid surface that allows it to resist external force, determines how liquids splatter on surfaces in space in terms of shape and size.

The experiment in zero-gravity was a new experience, Pantalos says. “Watching the splatter patterns as they happen was absolutely fascinating, because of the slightly different behavior without gravity being present,” he says. “The other thing ironically for me is I go to great lengths to keep everything inside the glovebox tidy. I was giving myself the first opportunity to intentionally make a mess.”

Blood splatter forensics is a complex science. It isn’t as simple as it may seem on TV: It relies on considerable subjective interpretation by a forensic analyst. Today, many of the surfaces on Earth where experts may find blood splatter are made of highly engineered materials, such as scratch-resistant cell phone screens, anti-glare windshields, or hydrophobic surfaces. The latest blood splatter science is trying to understand how these new materials impact splatter patterns, akin to the work Kowalske is doing in his doctoral studies.

Blood splatter patterns are the only type of forensics currently being tested in space, Kowalske says. This research could be used in future analyses of accidents or catastrophic events aboard the International Space Station.

For the space medicine community, of which Pantalos is a part, the main goal is maintaining people's health in space. However, the space medicine community also discusses what will happen when people die in space. This could lead to inquiries in astroforensics.