A different version of this essay was published in The New York Times Book Review.

A cloud is a protection against not caring, a symbol of the water cycle that makes this planet a living world capable of trees and affection, a tremendous cosmic breath at the unlikelihood that such a world exists, that across the cold expanse of spacetime scattered with billions upon billions of other star systems, there is nothing like it as far as we yet know.

Clouds are almost as old as this world, created when ancient volcanoes first released the chemistry of the molten planet into the sky, but their science is younger than the steam engine. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the chemist and amateur meteorologist Luke Howard, still in his twenties, noticed that clouds take certain shapes under specific conditions. He set out to create a classification system based on the newly popular Linnaean taxonomy of the living world, naming the three main categories cumulus, stratus, and cirrus, then grouping them into various sub-categories.

When a German translation reached Goethe, the polymathic poet with a passion for morphology was so inspired that he sent fan mail to the young man who “distinguished cloud from cloud,” then composed a series of verses for each of the main categories. It was Goethe’s poetry, translating the vocabulary of an obscure science into the language of wonder, that popularized the cloud names we use today.

A hundred and fifty years later, six years before Rachel Carson awakened the modern ecological conscience with her book Silent Spring and four years after The Sea Around Us earned her the National Book Award as “a work of scientific accuracy presented with poetic imagination,” the television program Omnibus asked her to write “something about the sky,” in response to a request from a young viewer.

This became the title of the segment that aired on March 11, 1956 — a heartfelt song to the science of the clouds, expressing Carson’s belief that “the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us the less taste we shall have for the destruction of our race.”

Although celebrated for her books about the sea, Carson’s literary career had begun in the sky. She was only eleven when her story “A Battle in the Clouds” — a tale inspired by her brother’s time in the Army Air Service during World War I — was published in the popular young people’s magazine St. Nicholas, where the early writings of Edna St. Vincent Millay, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and E. E. Cummings also appeared. Despite her family’s meager means — a neighbor would recall stopping by at dinnertime and finding the Carsons gathered around a single bowl of apples — she enrolled in a women’s college aided by a $100 scholarship from a state competition, intent on studying literature at a time when fewer than four percent of women graduated from a four-year university.

And then, the way all great transformations slip in through the backdoor of the mansion of our plans, her life took a turn that shaped her future and the history of literature.

Carson took an introductory biology course to fulfill her college science requirement which she had delayed for a year. She became captivated by the subject and her teacher Miss Mary Scott Skinker, who taught advanced topics like genetics and microbiology and delivered fascinating lectures on evolution and natural history. Carson eventually switched her major to biology, but she maintained her passion for literature. She expressed her aspiration to write about biology, and despite facing rejection, she continued to submit her poetry to various magazines.

While following in Skinker's footsteps to the Woods Hole Marine Biological Observatory and working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Carson's boss found her reports too poetic for a government publication. He encouraged her to submit her work to The Atlantic Monthly. Carson realized that poetry can manifest in numerous forms beyond traditional verse while working at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, where her boss perceived her reports as excessively lyrical. Carson's boss found her reports too lyrical for a government publication. Her boss encouraged her to submit her work to The Atlantic Monthly.Carson believed that poetry exists in various forms and that science aims to discover the wonder and beauty inherent in nature. She later received the National Book Award, presenting a new concept that science and poetry are not in competition, but rather complement each other. these words:

The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history or fiction; it seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.

Carson believed that the poetry in her writing was not a deliberate addition, but an inevitable result of writing truthfully about nature.

Rachel Carson challenged the idea that truth and beauty are adversaries, suggesting that writing about science with emotion deepens its authority. She paved the way for future writers to blur the line between science and poetry and embrace the wonder of the natural world.

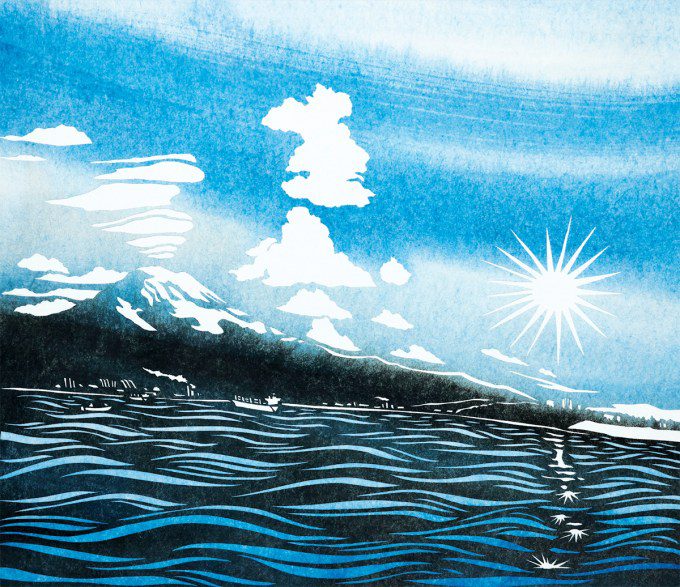

Carson approached her writing by describing the science of various cloud types while celebrating them as essential symbols of a process vital for life on earth.

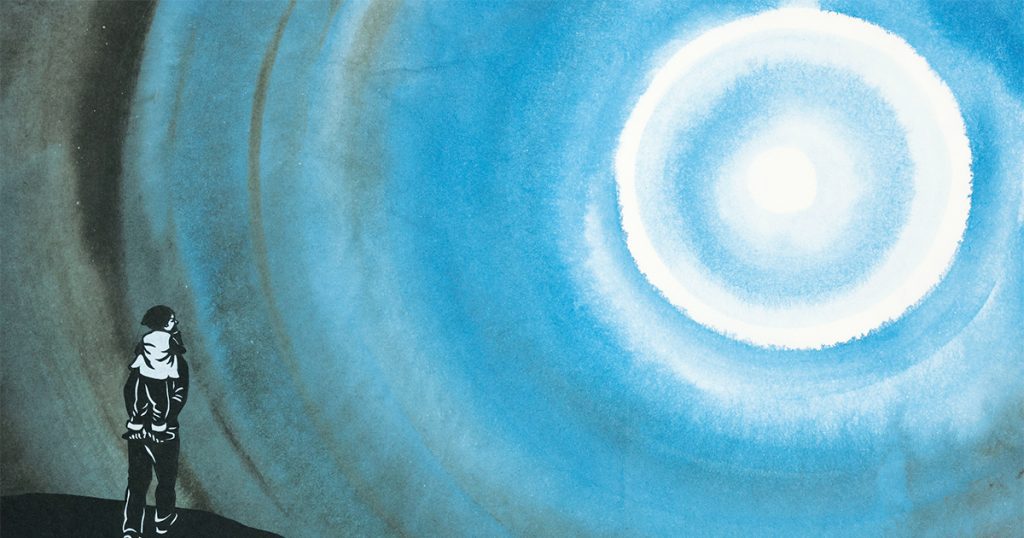

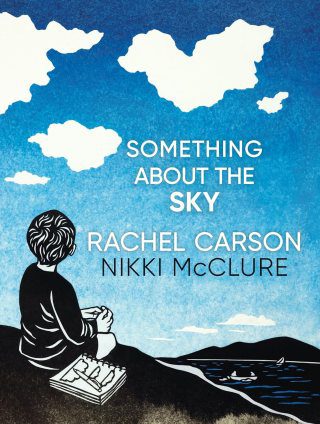

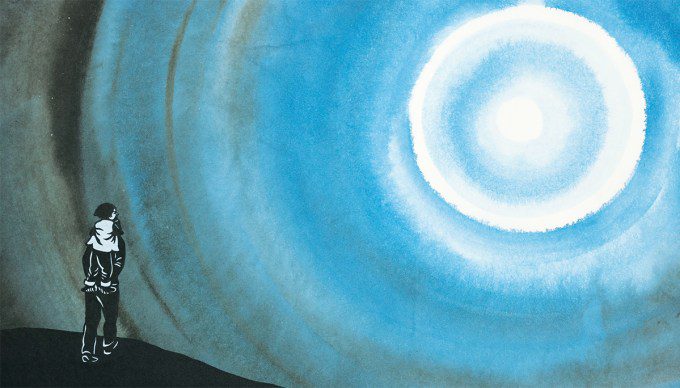

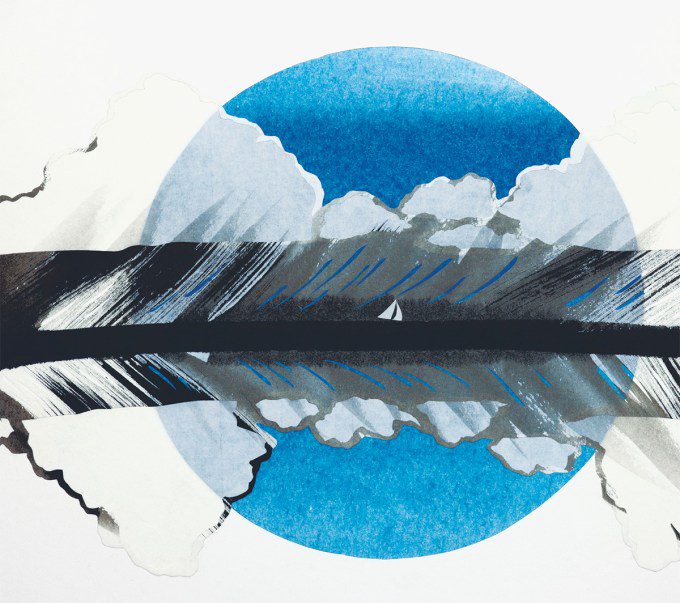

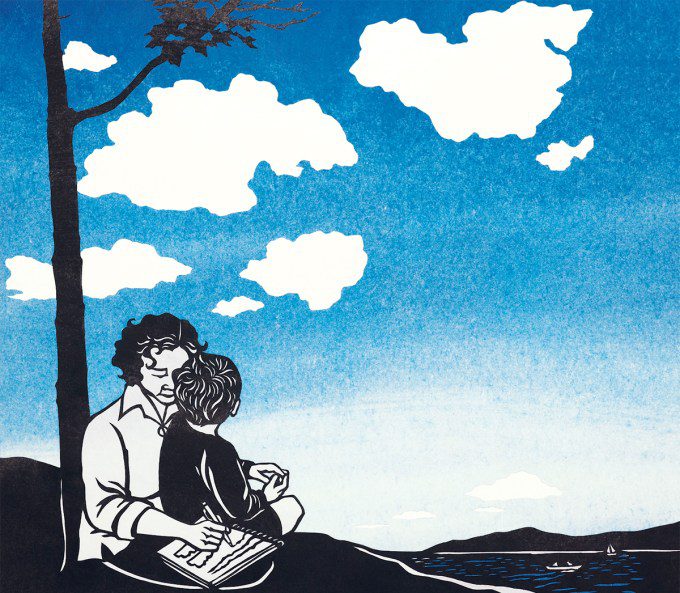

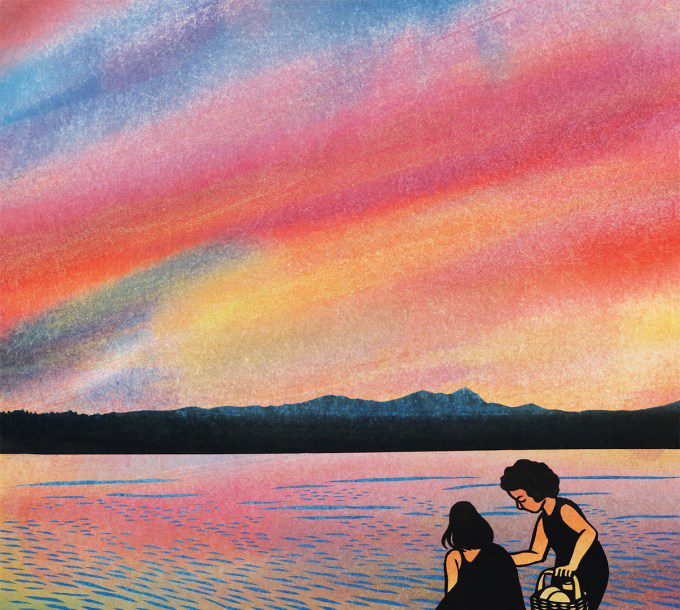

After discovering fragments of Carson's lost television script in a magazine, the artist Nikki McClure was inspired to locate the complete original and create lyrical illustrations for Something About the Sky, using her distinct cut-paper art, stark contrasts, and sharp contours to capture the softness of the sky. Orion A gentle and expressive visual poem emerges, boldly defying categorization, much like Carson's writing. Even though Carson never wrote directly for children, she used language that captivated children: wonder. Among the piles of fan mail at the Beinecke, there is a letter from a geology professor who, after comparing her to Goethe, shared how fascinated his eight-year-old son was with her words. Less than a year after Something about the Sky (aired, Carson adopted her grand-nephew Roger who had lost his parents twice. He is the young boy seen playing in McClure's illustrations. In what started as an article for Woman's Home Companion and later became the posthumously published book) was born.

Known for The Sense of Wonder, she wrote:

Something About the Sky

with the lively tale of

how the clouds got their names , then go back to Carson's thoughts on writing and the solitude of creative work the sea and the purpose of lifeA version of this essay was published in The New York Times Book Review. A cloud is a protection against apathy, a symbol of the water cycle that sustains this planet as a vibrant living world with trees and affection, a profound cosmic gasp at the unlikelihood of such a world existing, considering the vast cold space dotted with billions of other star systems, there is nothing quite like it that we know of. Clouds have been around almost as long as this world, forming when ancient volcanoes released the elements of the molten planet into the sky,…

A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.

Couple read article with the animated story of how the clouds got their names, then revisit Carson on writing and the loneliness of creative work and the ocean and the meaning of life.