The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has postponed its decision on Eli Lilly’s LLY.N experimental treatment for early Alzheimer’s disease and will convene an advisory meeting to discuss its safety and effectiveness, the company said.

The FDA’s decision was unexpected for company officials and many Alzheimer’s experts, who had anticipated full approval for Lilly’s drug donanemab this month based on clinical trial data last year showing the treatment was safe and effective.

No date has been scheduled for the advisory committee meeting, but it could be several months before it takes place. Eli Lilly shares were down three per cent, while shares of Biogen BIIB.O, which sells a competing drug, were up more than two per cent.

This is the second delay for the eagerly awaited treatment by the FDA after it refused to grant accelerated approval for the medicine a year ago.

Drugs like donanemab, which slow disease progression in early-stage patients, signify a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment, following three decades of unsuccessful attempts to combat the deadly disease affecting more than six million Americans, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

“This was definitely unexpected,” Anne White, president of Lilly Neuroscience, said in an interview, adding that the news came very late in the review process and the company had been prepared to launch the drug.

White stated that the FDA wants the expert panel to discuss some of the unique aspects of the clinical trial used in its request for traditional FDA approval, including issues surrounding efficacy and safety.

The FDA had held advisory committee meetings before approving Eisai 4523.T and Biogen’s Leqembi, which received standard authorization last year and operates in a similar manner. The agency declined to comment on its decision.

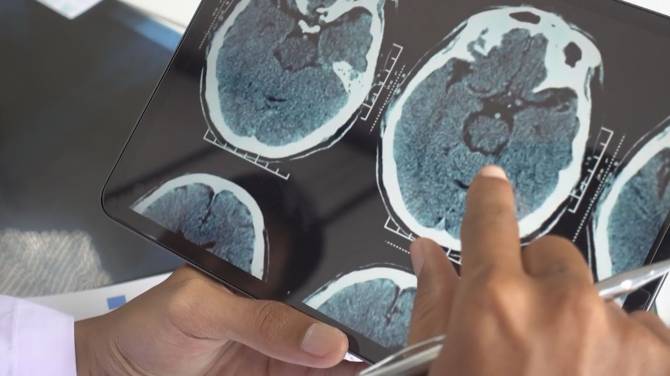

Administered through infusion once a month, donanemab is meant to clear a toxic Alzheimer’s-linked protein called beta amyloid from the brain.

The treatment reduced the progression of memory and thinking issues by 22 per cent to 29 per cent overall in a large clinical trial, roughly comparable to the 27 per cent reduction seen with Leqembi.

In patients with low-to-medium levels of a second Alzheimer’s related protein called tau, the drug slowed disease progression by 35.1 per cent compared with placebo.

Brain swelling, a known side effect of this type of drug, occurred in 24 per cent of the donanemab treatment group, while brain bleeding occurred in 31 per cent of the donanemab group and about 14 per cent of the placebo group.

In the trial, participants could stop treatment as soon as brain imaging showed that the drug had cleared the amyloid.

Lilly’s White mentioned that the design, as well as the use of tau to group patients and assess the drug’s benefit, were likely to be discussed at the advisory meeting.

‘EXTRA CAUTION’

Experts said the drug’s link to brain swelling and bleeding could be at issue. Three people in the company’s trial who received the treatment died.

Dr. Erik Musiek, a Washington University neurologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, had anticipated the drug to be approved this month. He pointed to donanemab’s higher rates of serious side effects compared with Leqembi as one possible reason for the FDA’s “extra caution.”

Patients might be able to discontinue treatment once the medication has effectively removed amyloid, which could be an advantage over Leqembi, a drug that needs to be taken twice a month indefinitely, according to Musiek.

Dr. Mary Sano, who heads the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai in New York, pointed out that the FDA might be finding it difficult to handle patients who stop the treatment but later need to start it again, potentially exposing them to more side effects.

“These medications can cause negative reactions. They are not cheap, and they require a lot of time for the patient. You really need to ensure that they bring value,” she explained.