On an early morning in June, New York City’s Prospect Park is peaceful and nearly empty: A few people sleeping on benches, a few more walking their dogs, and the birds chirping—exactly what Ben Mirin comes to hear, and they put on quite a show. Whistling, warbling, tweeting, and trilling, the avian residents of Prospect Park create an invisible orchestra. Mirin can identify them all: house wrens, northern cardinals, common grackles, mourning doves—even the Prospect Park Zoo’s peacock.

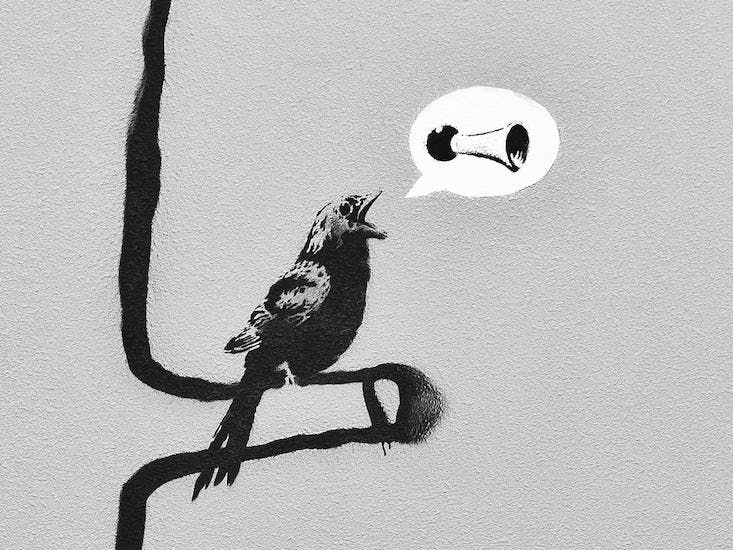

An ardent birdwatcher and an avid beatboxer, Mirin has combined his two passions into one unusual calling as a “wildlife DJ.” Under his professional moniker, DJ Ecotone, Mirin travels the world, records natural sound, and remixes it into songs that combine a bit of hip-hop, a bit of house, and a bit of something else entirely. “I feel like a folklorist,” Mirin says, “Except unlike Alan Lomax, I’m recording animals.”

Mirin is the co-creator and host of the National Geographic Kids show “Wild Beats.” He’s also the 2016 Artist-in-Residence at the Bronx Zoo, where he performs live. Beyond the pleasures of producing and performing, Mirin hopes to use his music as a means for generating conversation. He recently returned from a recording expedition in the Sierra Nevada, and in September, he’ll be traveling as a Safina Fellow to Madagascar alongside the prominent primatologist Patricia Wright to record the sounds of the island.

Nautilus recently caught up with Mirin, over birdwatching, to hear about his music. “Do you mind if we go off the path?” he asked, stepping over an orange Lifestyles wrapper in Prospect Park and into the brush. “It’s my way of feeling a little bit more wild.”

How did you first get into the birdsong music business?

I’ve lived in New York for three years, and in that time, I’ve felt cut off from the natural world in a profound way. I think a lot of people who come to New York experience that feeling. I wanted to reconnect with nature through what I was doing on an everyday basis. As a beatboxer, I have found myself in very good company among my fellow noisemakers here—the New York beatboxing scene is one of the best in the world.

Being able to experiment with sound through beatboxing was artistically and creatively rewarding, but I wasn’t connecting to the other half of myself—the naturalist, the birder. And so I decided to use beatbox as a bridge to the natural world. I started beatboxing alongside birdsongs that I would play on little samplers. It was just an experiment at first, but then people were really enthusiastic. It totally caught me off-guard. I was like, how does one do this for a living? That is a question I am still answering.

What has surprised you in the process of beatboxing nature?

One of the things I’ve discovered is that as a producer working with natural sound, your job is somewhat done for you. Both in nature and in the music studio, sound production follows a lot of the same rules: An individual voice makes itself heard by occupying a specific place in the mix, relative to other sounds in its environment. It’s not a shouting match. When you look at the sonogram of the sounds in an ecosystem, they fit together like pieces of a puzzle.

As a producer, that’s supposed to be your job: giving each instrument its own unique pocket in the overall soundscape you’re creating. But with natural sounds, evolution has already dictated that for you. So when you’re working with natural sound, you’re actually constructing a narrative that documents the relationships between voices in a place, relationships shaped by evolution, behavior, and the physical impact of landscape on sound. In a dense rainforest, certain sounds are going to carry better than others, and animals have evolved sounds to do just that.

If you hear a hermit thrush ten feet away from you, it’s a nice sound, to be sure, but the sacred beauty of a hermit thrush call really comes from the way it bounces around the forest. That gives it an irreplaceable musical quality that brings to bear the voice of the land as well as the voice of the bird. Having that in your mix as a producer, it’s like, “Oh my god, I’m not really an artist. I’m a messenger.”

Is there any one location where the bird life most impressed you?

I travelled to New Zealand at the beginning of 2014. New Zealand is famously called the “land of birds”—it has a lot of famous endemic species that live nowhere else in the world, like the Kakapo and the Kiwi. But I was actually struck by how little birdlife there was. That is symptomatic of the introduction of mammals, spearheaded largely by us. [When colonists arrived in New Zealand] we brought our cattle and sheep, and then we introduced rabbits to eat the weeds. There’s footage from the 1930s where there were so many rabbits you literally could not drive a car. So then [the colonists] said, let’s introduce weasels and stoats to kill all the rabbits. Well, where do most of the birds live in New Zealand? On the ground. So many bird species were completely decimated.

Kakapo have this incredible sound. They inflate and make this insane bass sound that carries through the mountains. The birds I did see were amazing, and very tame. The species still show the character of adapting in an isolated place.

Overwhelmingly, you find that there are two narratives when you go to these exotic places. On one hand, there are so many wonderful things to see. On the other hand, a lot of them are struggling to get by. Whether it’s climate change, or habitat destruction, or one brought on by the other, inevitably when you examine the world, through sound in particular, you end up with a narrative of our impact on other species.

How much of what you compose is interpretive versus literal?

I try to negotiate a middle ground between the two. Inevitably, by putting animal sounds into a human context, I am removing them from how they naturally occur. I don’t add any digital effects to change the sounds. There’s no autotune involved. When I’m making a piece, I turn off all the appliances in my apartment, hope that an ambulance doesn’t come by, and start listening. I note time codes where I hear something I find interesting. Then I’ll listen through again and excerpt these little moments. And the most satisfying part of composition often comes at that stage, because I’ll stumble across a recording where the entire melodic riff, or the central melodic idea of a song, is given to me.

I then assemble a kit of these dozens and dozens of sounds, and weave them together into a mix. Insofar as my voice can complement them, I inject beatboxing and singing.

Has your relationship with the music changed since you began recording your own sounds?

I’ve felt more comfortable inserting my voice into the mix actually, which is surprising. In the initial stages, I was connecting to nature through my headphones, and so the natural sounds felt sacred, things that could not be changed, other than to be diced apart. But now, every sound has a story: I was there. I can tell you what that bird was doing.

I think my vision for being a wildlife DJ very quickly codified around the idea of travelling around the world, recording animals sounds, and making music from them. And that’s now my whole process: capturing as much of a place as I can though sound, and then transforming my personal experience into a musical narrative. It’s rewarding to be involved in every stage of the process.

Is there something particular about birds that drew you to them?

Birds are my gateway drug. I got hooked at an early age, and it’s an addiction I’ve been unable to beat. They are these amazing barometers of a habitat’s wellbeing. Being able to “read the birds” is a way of gaining understanding about the place you’re in. And birds are everywhere we are. I think it’s a question everyone needs to ask: How is the world doing? You can look to birds for the answer.

I hear maybe six different things right now. I don’t see any of them. We’re such visual creatures, by evolution. It makes sense that we focus on what we can see. But we do have five senses. Why not use them all?

Madeline Gressel is the social media editor at Nautilus. Follow her on Twitter @maddiegressel.

The lead photograph is courtesy of Thomas Hawk via Flickr.