One evening last spring, I sat down at the American Museum of Natural History’s 85th annual James Arthur lecture, in New York, on the evolution of the brain. This year’s speaker was Richard Byrne, who studies the evolution of cognitive and social behavior, particularly gestural communication in the great apes, at Scotland’s University of St. Andrews. He began with a short video. Sitting in a mess of leaves and branches in Budongo, Uganda, a male chimpanzee shakes a branch with his right arm while scratching that arm with his left hand in a quick, back-and-forth motion. A female chimp in the shot looks on, apparently quite uninterested. “He waits, looks at her, she’s not reacting,” Byrne says. The male shakes the branch once more. No response; so he tries “the floppy arm,” instead, says Byrne, imitating it with his own arm raised above his head, dangling it in the air. “The male eventually gets what he wants,” he says: She comes toward him. “He’s able to groom her, and so forth.”

Byrne went on to make the case that almost all of the great apes—bonobos, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans—share not just the gestures above, but over 20 others as well. Byrne (in a video of a similar lecture, given to the University of Vienna a couple weeks later) flips to the next clip and connects the first male’s floppy arm footage to the same gesture filmed in a chimpanzee on Africa’s opposite coast, in Guinea, and again, in a captive lowland gorilla at a zoo. You see, he says, “many great ape gestures are not restricted to a single species at all.”

Do those species include us? After all, we share some 99 percent of our DNA with chimps and bonobos. Last month, Byrne co-published a review titled, “Where have all the ape gestures gone?” to compile evidence to answer this question. The answer is that some are still with us—though we may not think of them as a great-ape gesture.

Facing the Natural History Museum’s audience, Byrne stretches his right arm far out, hand cupped and face up. What does that signal? Obvious: “Give me.” It’s begging, and very popular among the apes. To Byrne, it’s a legacy of our great ape lineage, some 15 to 20 million years old.

He plays another video that was shot in Bugando, this one of a chimp “flicking” at another in an undeniably annoyed manner. The next shows a chimp from Guinea using the identical flick after her comrade has pitched a rock at her. “Get lost creep,” someone from the (University of Vienna) audience pipes in to narrate the chimp’s flick. Byrne laughs, “Yeah, exactly,” he says. “I don’t think any of you actually use that gesture”—the audience starts to whisper and laugh indicating that this might not be true—“yet you nevertheless know what it is.”

Does this mean we should be able to communicate with great apes? Well, in some ways, we already do. Zookeepers, who work with their animals for hours on end, often talk about the ability to understand the mental states and intentions of apes in their care. The apes seem to respond to keepers’ mental states, too. In 2007, Byrne showed that orangutans in zoos use gestures to get bananas, celery, and whole-grain bread from their keepers. When a keeper pretended to misunderstand the orangutan’s request, giving them bland celery instead of the obviously better banana, the orangutan repeated their same gesture at a quicker rate. When the keeper played completely clueless, the orangutan switched to brand new gestures that translated similarly: “Give me.” And the German news site DW reported, in April, “A zookeeper told us that gorillas in particular swear a lot if you teach them the signs for swear words.” Last year, at Busch Gardens in Florida, a gorilla gave the middle finger to another gorilla who kept throwing a rubber toy at her.

Fist-punching the ground is a gesture made by all bonobos and chimpanzees, and it’s seen in grumpy kids from time to time, too.

To others in the field, though, Byrne’s view relies too heavily on the backbone of evolutionary theory. “As a biologist [like Byrne], your first explanation of a phenomena is always the assumption that there has to be a biological root,” says Richard Moore, a cognitive scientist and philosopher at the Berlin School of Mind and Brain. Moore says great apes may not have shared, innate gestures. Rather, they have common motivations to relay. Those could be the same motivations that drive humans, he says. Plus, we share similar head-to-toe plans.

“Great apes have bodies very similar to our own,” says Federico Rossano, a cognitive scientist at the University of California, San Diego. “If you have the same body, engage in similar activities and have similar motivations,” he says, “chances are that you will develop similar signals.” He stresses that this does not imply that those signals are necessarily innate, nor that they are retained across the whole ape lineage.

To Rossano, in other words, while human communication, like the ability to speak, is likely rooted in great apes’ abilities to make and understand gestures, this does not necessarily mean that speaking is a more “highly evolved” form of gesturing. He believes instead that gestures arise out of daily actions. “When a baby ape gets carried around, it holds onto its mother’s sides below the armpits,” Rossano says. Eventually, touching Mom’s side below the armpit becomes a trigger for Mom to pick Baby up. If apes all engage in similar Mom-Baby piggybacks and other gestural behavior, it’s likely the gestures for these actions arose independently in each group of apes, due to similar body types and survival imperatives, he believes.

Fist-punching the ground, for example, is a gesture made by all bonobos and chimpanzees when they want you to move away. It’s pretty clear what it means when it happens, and it’s seen in grumpy kids from time to time, too. “Given the way that the human body works, when you bang on something, you bang with your hand or your foot, not your knee or your chin, because that’s how we’re built,” Moore says.

For Byrne, gestures still stand out from other traits. He plans to investigate the similarities between ape gestures and gestures made by pre-speech children with Virginia Volterra, who has studied gestures in children for many years in Italy and the United States. When you find that bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas have unique social systems, sexual behaviors, and manual skills, yet use the very same gestures to communicate the same desires—an over 90 percent overlap between bonobos and chimps; 80 percent with gorillas—he says, “I think it’s a little simpler to assume they reflect adaptations inherited from common ancestors.”

Byrne’s lecture hits at the heart of a deep debate. In fact, in primate gesture research, “that’s probably the main question today,” Moore says: “Are ape gestures learned or are they inherited?” As with most things, he says, “it’s most likely a hybrid story.”

Becca Cudmore is a science journalist. Follow her on Twitter @beccacudmore.

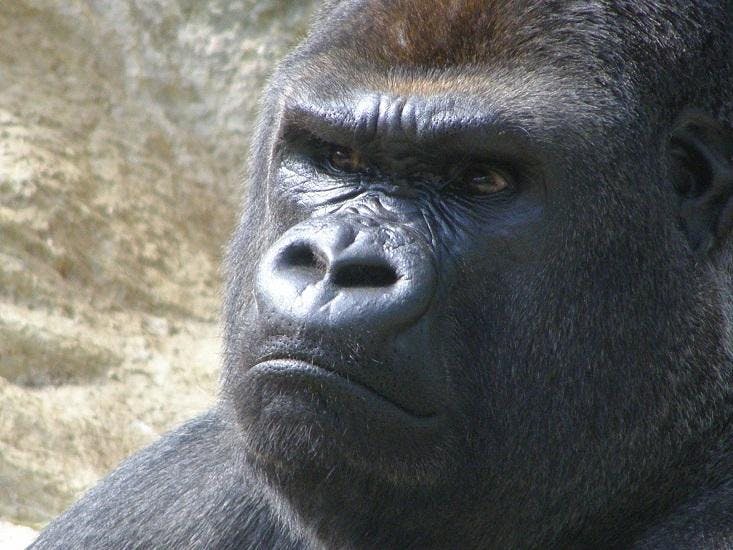

The lead photograph is courtesy of belgianchocolate via Flickr.