Early one Saturday morning in Las Vegas, I sat down at a Texas Hold ‘em poker table with seven or eight other men, all middle-aged. Being 30 at the time, I was the youngest player by about a decade. A couple of them were wearing Hawaiian shirts. It was too early for drinking, but one or two guys puffed on cigarettes as the cards were dealt. The buy-in was $75, far more than I’d ever paid for a poker game.

I played in a regular poker game in New York City, and I was feeling good about my abilities. I decided to use a conservative strategy to extend my time on the table: Only stay in a hand when I have cards worth playing. In retrospect, I was probably primed to be taken down a notch or two.

My plan quickly proved worthless. The luck of the cards wasn’t with me. My best hand was maybe a Jack High. Worse, the others at the table were betting aggressively and bluffing masterfully. Well, I assumed they were bluffing. I think I actually saw a player’s winning cards only once. I swiftly suffered the fate of fools with money. My opponents cleaned me out in five or six rounds. Poof! My 75 bucks were gone.

I gained very little from that experience—both financially and as a way to pass time. But I did learn one thing: I would have been better off if the game had involved less skill and more chance.

Coincidentally, laws in the United States tend to have the opposite opinion, and favor skill over chance. They regulate games of chance differently (and more strictly) than games of skill, and regard the former as gambling. Of course, both chance and skill play a role in nearly every contest, from poker to pingpong. But in the eyes of the law, it is more acceptable to participate in a game of skill, where those with knowledge, experience, or talent are more likely to prevail, than in a game of chance, where all players have the same odds.

In 2006, the U.S. Congress passed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA), which prohibited gambling enterprises from processing payments online from U.S. credit cards and banks. That law effectively crippled the sizeable online poker industry in America (for a sense of scale, the industry brought in an estimated $2 billion in 2005 worldwide). Now, authorities in states across the country have turned their sites to another target: the daily fantasy sports industry. Fantasy sports, in the ensuing effort to show that they are based more on skill than on chance, have in some ways succeeded far beyond their intention—they are, in many cases, more skill-based than the real sports on which fantasy players are betting.

Which is probably good news for them, as regards regulation. But where does that leave players like me?

Fantasy sports sites DraftKings and FanDuel let contestants enter for as little as $1, or for several thousand dollars. Contests are available in each of the four major U.S. sports leagues: Major League Baseball, the National Basketball Association, the National Football League, and the National Hockey League. Contestants choose a lineup of players in a particular sport with a limited fund of money, known as a “salary cap,” and can find out if they’re a winner as soon as the evening’s games are over.

In the case of fantasy baseball on FanDuel, for instance, contestants select a nine-player team consisting of a pitcher, catcher, and all the infield and outfield positions. Contestants can’t simply pick a roster of superstars. Each available player is assigned a salary for the day by FanDuel. Contestants must select a roster of players whose combined salaries add up to $35,000 hypothetical dollars or less. Ace pitchers can cost in the low-five figures, while elite batters usually run over $4,000, meaning it’s nearly impossible to stack a team with standout players. Points are accrued based on how those players do in games played that day. The challenge for contestants is to choose the nine players who will provide the most points, while staying within the salary cap. So, essentially, the skill needed to excel in daily fantasy sports is bargain hunting.

Honing one’s ability to spot value assembling fake rosters of professional athletes can ensure someone a higher likelihood of success than years working on hitting a baseball.

Some of the networks that carry sporting events hold large stakes in the daily fantasy portals. Those sites, in turn, buy advertising. DraftKings recently struck a deal with ESPN to buy $250 million in ads over the next two years. The sporting leagues also have lucrative marketing deals with them. In late 2014, the NBA entered an exclusive marketing sponsorship with FanDuel and bought an equity stake in the site, which is currently the industry’s leader. The startups make money by taking in entry fees for the hundreds of contests they offer daily. They return the bulk of that money as prizes to winners, keeping about 10 percent of what’s anteed. Last year, players anteed up $3 billion in entry fees on DraftKings and FanDuel. Together, the websites hauled in just short of $300 million in revenue, nearly three times what they took in back in 2014.

But an incident in late September of 2015 that some saw as tantamount to insider trading attracted unwanted attention to the industry. A DraftKings employee, Ethan Haskell, reportedly accidentally published a blog on the site data on which football players were the most rostered ahead of the third week of the NFL season. The fantasy sites set prices at the beginning of a contest, and they don’t change before users have to lock in their rosters, just as the real-life games start. By knowing who was on other fantasy team lineups, contestants might have noticed undervalued players chosen by their peers that they would have passed over otherwise. Worse, it soon began to seem like employees of either site, while banned from playing on the portal where they worked, were using this information to win thousands of dollars on their competitor’s platform. Haskell, for instance, won $350,000 in a contest on FanDuel the same week he leaked the data. An independent investigation commissioned by DraftKings later determined that Haskell received the information he leaked too late to affect the FanDuel contest, but by then the damage was done.1

DraftKings and FanDuel quickly forbade their employees from playing daily fantasy contests, but Pandora’s box was open. Nevada quickly deemed that DraftKings and FanDuel were hosting gambling and asked the companies to secure licenses. And in November, after an investigation into the industry, New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman ordered the web sites to cease operations in the Empire State. New York was home to, according to an affidavit submitted by DraftKings Chief Financial Officer Tim Dent, more than 5 percent of its users and 7 percent of its entry fees in the first 10 months of 2014.

Playing online fantasy sports for money was already banned in Arizona, Iowa, Louisiana, Montana, and Washington state when DraftKings and FanDuel launched in 2012 and 2009, respectively. But since the Haskell incident, Alabama, Illinois, and Texas are also taking action against the sites.

In a prescient move in January 2015, FanDuel approached Anette Hosoi, a professor of mechanical engineering and mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and asked her if she’d analyze the results of daily fantasy contest entries put in by between half a million and a million players to see if their offerings were more games of skill or of chance. Hosoi is an avid mountain biker and snowboarder, and in the fall, she plays season-long fantasy football. And in 2012, she founded the Sports, Technology and Education @ MIT (STE@M) program.

Many of STE@M’s projects are mechanical in nature—redesigning hockey sleds used by Paralympic athletes or determining the optimal strategy for team pursuit cycling races. But the FanDuel project allowed Hosoi to investigate a dataset for insight as to the role of chance in the way fantasy contests are currently designed. “It’s such a great mathematical problem,” Hosoi says. “Someone gives you a pile of data, and you see if you can figure out if it arose by chance.”

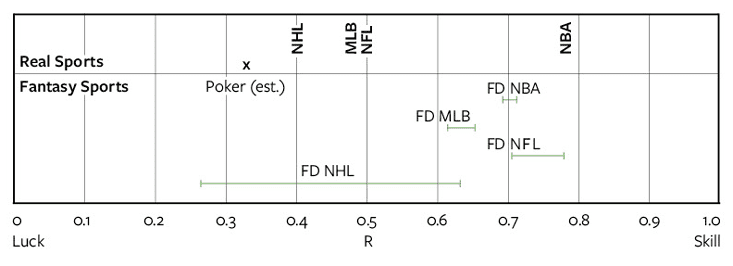

Real-life versions of sports involved less skill than their fantasy corollaries.

A self-described visual learner, Hosoi immediately began plotting the data. First she compared the performance of FanDuel players to that of lineups that were randomly constructed by computer simulation. If the fantasy contests were largely chance-based, over hundreds of games the simulated lineups should score as well as the human-chosen ones. But real rosters significantly outscored the random ones. When Hosoi tweaked the algorithm to make the simulated lineups more realistic (for instance, ensuring that more money was set aside for quarterbacks than kickers in football games), the human-picked teams still overwhelmingly netted more points.

Hosoi also developed a metric for measuring the relative skill involved in any contest based solely on players’ outcomes. She began by plotting the results of FanDuel players on a graph where the x-axis was a player’s win percentage in the first half of a season, while the y-axis was the win fraction in the second. In a purely chance-driven contest, one would expect a symmetrical distribution around 50 percent on both axes, right at the center of the graph, since the odds of success are even. In a skill-based game, however, there will be a distribution of outcomes, which Hosoi says indicates multiple skill levels. Poor players fall at the lower left of the array; elite ones find themselves on the top right of the array.

In a perfectly skill-based competition, plotting the results of each contest would create a diagonal line in the middle of the graph. The farther off that line the array is, the more chance is inherent in a contest. This distance can be translated into a skill-factor value that Hosoi calls “R.” The higher R is, the more skill is involved. “The R value is totally independent of the rules of the game,” says Hosoi. “All you have to do is give it the set of outcomes. So I can apply it to real sports, blackjack, anything you want.”

When Hosoi compared the R values of FanDuel contests to actual professional sports teams, she found that the outcomes of real-life sports involved less skill and more randomness than their fantasy corollaries (with the exception of basketball, whose many opportunities to score reduce its randomness). In fantasy hockey, skilled contestants will succeed slightly more often than elite NHL teams will. In a real-world hockey game, a weird puck bounce can lead to a fluke goal. Because hockey games are relatively low-scoring, moments of randomness can have an outsized impact on the outcome of a matchup. To a lesser extent, the same is true in baseball and football, both games where scoring opportunities can be hard to come by.

It’s weird to think that honing one’s ability to spot value when assembling fake rosters of professional athletes can ensure someone a higher likelihood of success, as measured by victories, than spending years working on hitting a baseball or shooting a three-pointer. (Of course, being an elite professional athlete will earn you a lot more money.) But the best daily fantasy players do have a well-defined set of skills, which they hone over thousands of hours of practice. Chief among these: an acute attention to detail.

Peter Jennings is best known as the winner of DraftKings’ Legends Series Fantasy Baseball Championship in 2014, where he outscored other elite daily fantasy players in 50 contests over five days at a resort in the Bahamas to claim a $1 million payout. Jennings, who is 28 years old and lives just south of Denver, quit his job as a stockbroker in 2012 and now makes his living playing daily fantasy games, pulling in six figures yearly.

Jennings enters thousands of contests per day, sometimes submitting just one or two optimized lineups per sport. He spends 80 to 85 hours a week researching and playing fantasy sports. He watches hundreds of games to assess some of their more subjective aspects, like how well offensive lines block in football or if a basketball player sustains a minor injury that might impact his play.

Even if he’s not watching film, he’s still weighing dozens of factors through custom mathematical models he’s developed to assemble what he thinks will be an optimal high-scoring lineup each day. “In a sport like baseball, there’s so much data,” he said. “I know a lot of successful [fantasy sports players] that don’t watch baseball.”

According to an affidavit he supplied on behalf of DraftKings for its New York State legal proceeding, in baseball, he accounts for batted ball speed (a measure of whether a hitter is making good contact), weather forecasts, air density (which impacts how far a hit ball might travel), which umpire is calling balls and strikes, and even player psychology—like if a pitcher is trying to bounce back from a humiliating outing.

But, as good as he is, Jennings cannot rely solely on his data-mining. He also needs the betting site to leave something on the table when it sets prices.

In a statement sent to Nautilus, FanDuel explained that it sets players’ prices “by analyzing different data points and statistics (generally on a daily basis) in order to make projections regarding fantasy performance. At the beginning of each season, we price each active player. We then change prices daily, or weekly for NFL, based on factors such as individual performance, team performance, opposing team’s defense and ability and historical ownership percentages.” But they could do better.

Fantasy experts like Jennings exploit inaccuracies in how FanDuel and DraftKings price players, looking for athletes who are likely to produce a lot of return but don’t cost much. Prices aren’t perfectly predictive of how a player might perform, or changed based on the popularity of a player among other fantasy players. They are also set up to 24 hours in advance of games, so that news regarding weather, injuries, lineup changes, and so on can make prices inappropriate by the time the first pitch is thrown.

Essentially, the skill needed to excel in daily fantasy sports is bargain hunting.

According to University of Chicago economist Steven Levitt of Freakonomics fame, the daily fantasy portals could stymie Jennings and his fellow elite contestants by adjusting the prices they put on athletes so they rise with demand. Improving their algorithm until they hit on, essentially, the perfect model for accurately predicting which athletes would perform well on a given day, and then pricing them accordingly, would eliminate the inefficiencies exploited by the elites.

“The sites could take much of the skill component away,” Levitt, who performed an analysis similar to Hosoi’s on Texas Hold ‘em a couple years ago, wrote in an email. “There would be no bargains.” This would have the benefit of making the playing field more even for contestants, and broadening the pool of winners.

According to a study by poker strategist Ed Miller and Daniel Singer, leader in Media and Entertainment Practice with McKinsey & Company, most people who play on DraftKings and FanDuel are lambs being brought to slaughter. In a sample of contests from the first half of the 2015 Major League Baseball season, just 1.3 percent of daily fantasy players won 91 percent of the winnings.

“It’s a game of skill in that there is very little opportunity for people to consistently win over time,” says Andrew Billings, director of the sports communications program at the University of Alabama and the coauthor of The Fantasy Sport Industry: Games within Games. “But they’re advertising the exact opposite— that any schmuck from across the street can pick a few players and win a million bucks.”

Peter Jennings is one of the world’s best fantasy sports players, but it’s not just the computer algorithms he uses to choose players that give him an advantage over a casual player like me. Jennings also thinks differently about sports than I do—and thinks more about them.

Over the course of mid-May and early-June, I assembled FanDuel lineups for 30 different 50/50 fantasy baseball contests, where the top 50 percent of entries all win payouts equal to 80 percent more than the entry fee.

Because I’m an experienced season-long fantasy sports player, I felt I needed at least a baseline amount of knowledge to have a chance of winning the daily contests. I was dependent on ESPN’s “Hitter matchup ratings,” a free advice tool that indicates how the left-handed and right-handed batters on a particular team were likely to perform against the pitcher they faced that night. For pitching, I tried to save money by finding a less-than-elite hurler facing a crappy team. (This season, my beloved Atlanta Braves qualifies as one of those squads.) That way, I could invest in multiple hitters capable of doing damage, even if a few carried high price tags.

When I spoke to Jennings after I’d played my FanDuel contests, we had an interesting discussion about San Francisco Giants catcher and former National League MVP Buster Posey. I’d rostered him several times while I played and seriously considered him for most of my games. But Jennings dismissed him almost outright. If there’s one position he skimps on, it’s catcher. It’s the position that offers the least return on investment; so fielding a low-priced catcher usually won’t cost you a ton of points relative to your peers. Further, Posey, Jennings said, plays in “a pitcher’s park,” meaning it’s harder to hit home runs because of the swirling winds near the San Francisco Bay. In fact, Jennings is only likely to have Posey on one of his teams if the Giants happen to be playing in Denver’s Coors Field, the ultimate hitter’s park thanks to the high-altitude city’s thin air.

With my nominal research I put together a record of 14-16, a roughly 47 percent win fraction. But that kind of winning percentage means that daily fantasy sports is not a money-making proposition for me.

—Nikhil Swaminathan

At the same time, showing that more-skilled fantasy players have an advantage over others is key to the fantasy sports industry’s survival. To avoid legal headaches, they would be well advised to keep their algorithms vulnerable to exploitation, and keep in place a system where an elite cadre of experts run roughshod over unsuspecting noobs.

The industry needs to negotiate these tradeoffs, explains Hosoi. “That tells me there’s some pricing strategy that’s going hit that sweet spot, where you’re within the definition of skill, but it’s still fun for a broad range of people,” she says.

For the moment, daily fantasy looks like it will live on in New York. The state senate passed a bill at 2 in the morning on Saturday, June 18, proclaiming DraftKings’ and FanDuel’s contests games of skill. The bill, which is identical to one passed by the state assembly the day before, moves on to Gov. Andrew Cuomo to sign and put into law. But legal experts expect that the challenges to the industry will continue—as will the questions about skill versus chance. The next battleground for the fight is expected to be Illinois.

The New York legislation goes some way toward protecting less-skilled players, by requiring that high-skill and high-volume players are clearly identified on the sites. Abraham Wyner, a professor of statistics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business who wrote an affidavit in support of DraftKings’ contests being games of skill, explains that chance can have a greater impact on outcomes when skill levels are well matched. For instance, in an Olympic sprint event, all participants are blazing fast, so a runner’s start or the lane they’re assigned to could mean the difference between winning and losing. Likewise, it’s tough to predict the victor between two chess grandmasters, but the outcome is rarely in doubt when one plays an amateur.

And that gets at the very essence of chance versus skill in contests. Skill-based contests tend to exclude people who cannot succeed—to wit, it’s been years since I last played chess. Chance games, on the other hand, pull the floodgates wide open (see, for instance, state lotteries). According to Hosoi’s R-value analysis, daily fantasy sports are far more skill-involved than, say, Texas Hold ‘em, the online version of which is slowly making a comeback in states like New Jersey, Delaware, and Nevada. It’s not chance in fantasy sports that we should be cautious about—it’s keeping the hapless sheep away from the well-prepped wolves.

Nikhil Swaminathan is a science and technology journalist based in Oakland, California. He’s a contributing editor at Archaeology and his work has appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Mother Jones, Psychology Today, and Wired.