Mintamir makes sure all five of her children wear shoes, so that they don’t share her fate. She wants to protect their feet from magic.

She lives in the corner of a cornfield in Northern Ethiopia, in a straw-thatched hut. The walls are framed with eucalyptus branches, plastered over with layers of mud and dung. Inside the hut, pasted on one of the walls, there is an old calendar, with a photograph pinned in the upper left corner.

The photograph shows Mintamir holding a child. She wears a faded blue dress and a black headscarf. A second scarf, with hues of red, green, and blue, is tied around her waist. An intricately fashioned crescent tattoo runs across her lower jaw and over her chin, stopping right below her earlobes. She looks away from the camera. Her face is expressionless.

Two men stand beside her, looking into the camera. Their faces are also expressionless. The man on her left is her brother, dressed in a light brown shirt and trousers. The man next to him has the upright posture of a soldier. He is Mintamir’s husband, bald, in army khakis, with a black belt and a green coat. Palm trees against a blue sky make the background.

There is something unusual in the photograph, but easy to miss at a quick glance: Mintamir’s legs.

Mintamir was in her mid-20s, and a mother of two kids, when the studio photograph was taken, one evening, 14 years ago. Her brother had insisted that they must take a family photograph. He was afraid that Mintamir was about to die. Mintamir’s feet and lower legs were swelling and gradually disfiguring. The day after the photograph was taken, the family reached a church in Gondar city in northern Ethiopia. Mintamir’s brother had heard from someone in his village that the church had holy water that might be of help. A priest at the church took water from a nearby stream, said to be holy, and sprinkled it over Mintamir’s feet while praying. They returned home to the village of Gumbi in the town of Finote Selam.

Time passed. Mintamir’s feet kept swelling. They reached double their normal girth, with some roughening of the skin, and they started to smell bad. Her husband, who had just returned from the war between Ethiopia and its northern neighbor Eretria, started to spend more nights away from home. Mintamir heard from neighbors that he was living with another woman. Some nights he came home, slept with her, and left early in the morning. She let him. She hoped that he might just come back. Mintamir had three more children with him. He might stay for the sake of the children, she hoped. She was no longer attractive to him, she thought.

One day, he just stopped coming. It’s now been five years since Mintamir has seen him. He has remarried, she has heard. He has children with his new wife, she has heard.

Mintamir is suffering from a disease that few people have heard of, called podoconiosis. A less known form of elephantiasis, it is not caused by bacteria, or viruses, or parasites, but by walking barefoot in red clay soil. It is completely preventable and curable. Its treatment requires just clean water and soap to wash the feet, bandages to compress the swelling, and shoes for protection.

When she was growing up, Mintamir hardly wore shoes, nor did anybody else in her family. Most people walk barefoot in rural Ethiopia. Some communities are so poor that they cannot afford shoes. Even if someone manages to buy a pair, the shoes are kept safe in the house, to be worn only on special occasions. Or they walk barefoot carrying their shoes slung on their shoulders, and don them only after reaching their destination. Wearing shoes all day can also be seen as a sign of laziness. Some find it hard to plough their field wearing shoes because the mud gets in, making the shoes heavy. For others, wearing shoes is just uncomfortable.

Ten of the 17 main diseases were chosen for financial support: Podoconiosis was left behind.

Many victims of podoconiosis are not aware of the cause of their disease. Some think that the disease is caused by too much exposure to the sun or by the curse of God. Others blame magic. “I mistakenly stepped over a magic herb,” Mintamir says. “It was placed in my way by somebody who was jealous of my beautiful and slim feet.”

Podoconiosis begins with a burning sensation and itching in the feet. The feet swell first, and then the lower legs. The skin thickens, darkens, and roughens. Pea-shaped lumps and bumps begin to appear. In extreme cases, the toes harden, lift off the ground, and lose their shape and nails. The lumps grow bigger, darker, rougher, tougher, and mossier, enveloping the foot and the lower leg, which can swell to up to five or six times the normal girth. The legs become heavy and unwieldy. They weep with pus, attracting flies. Shooting pain strikes at regular intervals and incapacitates patients for days. If not treated in time, podoconiosis cripples people for life. Those affected are ostracized by their community, expelled from school, and sometimes even turned away from places of worship. Many isolate themselves, like Mintamir. Others turn beggar or commit suicide.

Podoconiosis is also a neglected disease. In fact, it may be the most neglected disease on earth.

Around 6 million people in about 15 countries are estimated to be suffering from podoconiosis, primarily subsistence farmers who walk barefoot and live in Africa, Central and Southern America, and South Asia. Half of the world’s sufferers live in Ethiopia, where they make up 3 percent of the population. Almost half of Ethiopia is at risk of getting the disease, according to preliminary estimates by Kebede Deribe, research fellow at Brighton and Sussex Medical School in the United Kingdom.1 Northern Ethiopia, where Mintamir lives, has one of the highest concentrations of people affected by podoconiosis in the world. Five non-profits, four of them affiliated with the church, treat podoconiosis patients in Ethiopia. But, because of limited resources, fewer than 4 percent of patients have access to treatment. The Ethiopian government doesn’t provide any.

In 2010, the World Health Organization launched its first report on neglected tropical diseases, which included a list of 17 “main” neglected tropical diseases. These included dengue, trachoma, and lymphatic filariasis. Podoconiosis did not make the list. It fell into a sub-category of seven “other” neglected conditions, for which the global health agency still does not have any formal program. (The agency recently scrapped the category of “other neglected conditions” entirely.)

Two years later, the World Health Organization released a roadmap to control and eliminate those 17 diseases by 2020. Shortly afterward, a group of rich nations, pharmaceutical companies, and donor agencies led by Bill Gates assembled at the Royal College of Physicians in London and signed a declaration modeled after the World Health Organization’s goals. Ten of the 17 main diseases were chosen for financial support: These were mostly diseases that were infectious, global, affected many people, and required drugs. Millions of dollars were pledged. Podoconiosis was left behind. It didn’t satisfy the requirements. It is not infectious. It does not kill; it just disfigures and disables. Pharmaceutical companies are involved in aid decisions at the highest levels, which steers money away from podoconiosis. After all, no pharmaceutical company manufactures shoes.

At 9 in the morning, the January sky is clear and the wind is light. Birds are chirping. Cocks are scurrying. Women and girls carry bundles of firewood and yellow water cans lashed to their backs like backpacks. My interpreter, Fasil Girma, and I are sitting on a metal bench outside Mintamir’s hut. Mintamir’s daughters, wearing green and blue shoes, are playing outside with other girls from the neighborhood. They sneak a peek at me, laugh, and run back to play again.

I go inside to see what Mintamir is doing. In the outer room, sunlight filters through the chinks in the walls, where mud has fallen off, revealing the eucalyptus skeleton. The light casts a crisscross pattern on the opposite wall. With circular motions, Mintamir is carefully pouring corn paste from an earthen pot into a big black pan. The pan rests on a mud stove. Noticing the dimming flame inside the stove, Mintamir shoves more corn stems into it. The flame comes alive in hues of bright orange and yellow. She is making injera—Ethiopian bread, large, round, soft, and flat. A metal cross hangs from a black thread around her neck. Before long, she sits herself down on a tattered yellow-and-black mat folded carelessly on the floor.

She finds it difficult to stand for long. Her feet and legs below the knee are now swollen to what looks like more than double the normal size. Skin has gathered in thick folds near her ankles. Last year a lump, the size of a pea, appeared on her left foot near the toe cleft. Flies gather around it.

Mintamir, who is about 40 years old, has stopped going out. Not only has her husband gone, but neighbors have distanced themselves. Friends have turned away. Invitations to birthdays, weddings, and funerals have stopped. She goes alone to the church and returns alone. There is no company if she goes to the weekend markets. Too ashamed to take part in Epiphany, which is a three-day Ethiopian festival celebrated by Orthodox Christians, she listens to the distant revelry sitting in her hut.

On most afternoons, after finishing her chores, Mintamir likes to sit at her favorite place, the doorway of her hut. From here she can watch the world go by. “I want to go out, talk to people, laugh with them, feel human again,” she says, looking down. Mintamir doesn’t believe that her feet can ever return to normal. She fears that her children may catch the disease from her. Mintamir has heard from somebody that the disease runs in families.

After lunch I walk with Mintamir’s son, Mulusew, 21 years old now, to the family’s field, which is lying fallow after the harvest. Being the eldest, he takes care of the field and brings money to the house. “It is not enough but we try to manage,” he says as we sit under a big tree in the middle of the field. A bunch of men, in the nearby field, are trying to pull down some eucalyptus trees using ropes. Mulusew couldn’t study, as he had to shoulder the responsibility for his family after his father left. But he is happy that two of his sisters do. Primary education is free in Ethiopia.

When asked about his father, he says that he feels angry that his father left him, his siblings, and his mother to fend for themselves. “But I miss him,” he says. Mulusew has a quiet demeanor and speaks only when required. As a teenager, he faced stigma for being Mintamir’s son. Many times, in the past, when he went to play football with other boys, they said his feet smelled like his mother. “I fought with them,” he says. Mulusew never told this to Mintamir. He wants to marry now. “What if your wife gets the disease?” I ask him. “I will leave her,” he says. “I have already lived enough with shame.”

As evening falls, I learn from Girma that Mintamir is sending Mulusew out to buy vegetables. She plans to make a special dinner for me. I ask her not to. I am carrying my own food, I tell her. “I would feel happy. Nobody comes to my house. You have,” she says, adding that she is a good cook.

It is one of the best potato curries I have ever eaten in my life.

Late in the night, I ask her what she wishes for her husband. “I curse him to have the same legs as mine. I curse him that he suffers like me,” says Mintamir.

Podoconiosis began to be mentioned very sporadically in scientific papers in the late 1800s. In 1886, August Hirsch, a German physician who pioneered the field of geographical medicine, suggested that the cause of the disease must lie in the soil. Then, in the 1970s, a British doctor working in Ethiopia, Ernest Price, noticed that the disease was clustered in certain parts of the country, especially the highlands and in regions where there was red clay soil of volcanic origin. It ran in families, and affected farmers who walked barefoot.

Price also found that the disease had once been prevalent in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and the Canary Islands, but had since disappeared there. In Morocco, for instance, the disease used to be described in a French phrase that meant “as common as water in streets.” Urbanization, commercial plantations, and the use of footwear had gradually become common there. Price interpreted these developments as possible ways to control the disease.

He and his colleagues took X-rays of soil samples, and found large amounts of ultrafine clay minerals, including amorphous silica, iron oxides, and aluminum. These particles are produced during the chemical breakdown of lava rocks. Price found the same minerals in the skin tissue and lymph nodes of barefoot individuals that had the disease. He also observed that the disease did not progress if people wore shoes.

Giving shoes away is a great help, but it is only a start.

Price hypothesized that particles like silica get absorbed in the foot and trigger inflammation in the lymph vessels. Inflammation is the first defense of the body against foreign invaders. However with continuous exposure, the inflammation gets out of control, and starts to damage the lymph vessels. To counter the inflammation, the body releases certain chemicals, and produces collagen fibers that compress the lymphatic vessels. The obstructed lymph leads to the accumulation of fluid, which manifests in more swelling. His hypothesis, however, is yet to be tested, and some contemporary scientists are skeptical. “I have a great reservation on the sole lymphatic-obstruction hypothesis,” says Wendemagegn Yeshanehe, an independent dermatologist in Ethiopia. It has also been observed that in some cases, antibiotics reduce the painful attacks, which may be inconsistent with lymph blockage. Scientists remain uncertain about exactly which minerals cause podoconiosis, and how.

Based on his observations, Price coined the name for the disease from Greek words—Podos meaning, of the foot; and Konion, meaning dust. After his death in 1990, research on the disease stagnated—until 2002, when Gail Davey, a British epidemiologist then teaching at Addis Ababa University, became interested. Davey is now a professor at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, and has made the school a global hub for podoconiosis research.

A sort of crusader of podoconiosis, Davey has conducted about 40 interdisciplinary studies on the disease in the past decade. Another dozen studies are now being carried out. She has found that about 63 percent of the chance that an individual will develop podoconiosis is determined by genetic factors, whereas the remaining 37 percent is due to environmental factors, such as wearing shoes.

She is also overseeing an ongoing three-year randomized control trial to test the effectiveness of podoconiosis treatment. A total of 690 patients will be recruited in Ethiopia. The idea is to compare foot-care management in a community against the standard treatment, which is no treatment at all.

The pharmaceutical industry donated 1.35 billion pills in 2013 mostly to fight the five diseases chosen by the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID. These five were in turn chosen from among the 10 diseases singled out in the London declaration. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s senior program officer, Julie Jacobson, emphasizes the importance of pharmaceutical partners to the decision. There were pharmaceutical partners who committed to donate drugs for specific diseases. “Their commitments drove the commitments of others,” says Jacobson. Podoconiosis was not picked. “We don’t work in rare diseases or uncommon health infections. We don’t do those,” says Jacobson. “There is always a push to do more and more but that is not the best use of resources. We have decided to not expand our list of diseases.”

Which is not to say podoconiosis doesn’t have its corporate sponsors. A Los Angeles-based shoe company called TOMS, short for Tomorrow Shoes, has been donating shoes to Ethiopia and other developing countries. For every pair of shoe that TOMS sells, one pair goes to a child in a developing country, for free. It is a “One for One” concept that entrepreneur Blake Mycoskie pioneered when he founded TOMS in 2006. The concept is now emulated by many other companies. Mycoskie, 39, is a college dropout from Dallas, and a former contestant in the television reality show The Amazing Race. Today he likes to be called the Chief Shoe Giver. TOMS claims to have given away about 35 million pairs of shoes to poor countries, and it is one of the main funders of the National Podoconiosis Action Network, a non-profit based in Ethiopia. Giving shoes away is a great help, but it is only a start.

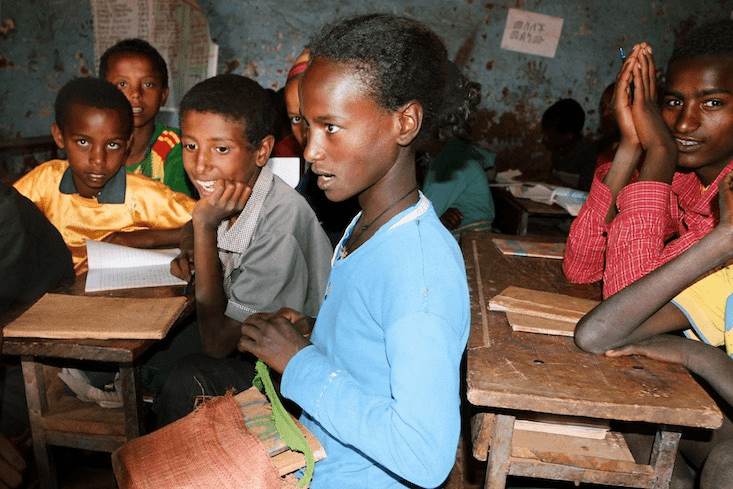

Last year in May, Yewela Primary School was one of the schools in northern Ethiopia where TOMS canvas shoes were distributed. A 14-year-old, Yezina Simachew, who was in seventh grade when I met her, received shoes along with her classmates. When they wore out during the monsoon season she went barefoot again. Simachew has been asking her father for a new pair of shoes, but did not get them. The shoes of her friend, Weynshet Dresse, also got spoiled. Dresse’s father told her that only lepers wear shoes. “He said why you need shoes, when your brother is not asking for it,” she tells me.

Almost all of the students in the class know about podoconiosis. They heard about it for the first time during the shoe distribution. One teacher at the school says that although shoes help, it may be even better to educate children about podoconiosis through the school curriculum.

Even physicians working in the government health centers have an education gap. “None of us ever heard or read about it in our medical curriculum,” says Tariku Belachew, Chief Executive Officer of Debre Markos Referral Hospital in Northern Ethiopia. In some cases, when podoconiosis patients approach a health center, the physicians turn them away, because they cannot diagnose the disease or distinguish it from lymphatic filariasis. Many physicians in Ethiopia believed that the disease is incurable. The health ministry is currently preparing a manual for health practitioners to train them to manage swelling caused by podoconiosis and related diseases.

Oumer Shafi Abdurahman, a 32-year-old coordinator for neglected tropical diseases in Ethiopia’s health ministry is aware that shoes and bandages have treated many podoconiosis patients. But he argues that the scientific evidence for the treatment’s effectiveness is incomplete. Davey’s controlled trial will help fill this gap.

About 7 kilometers from Mintamir’s house, off the town’s main concrete road, a narrow dirt lane leads to the Amhara regional state health center. An old poster, tattered and soiled, is tied between two eucalyptus trees by an arched iron gate. The poster invites people to be tested for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. Inside the health center, there are several tin-roofed, concrete-floored rooms. Each is for a different medical purpose. When I visit, the 10 a.m. January sun is warm enough for most of the waiting crowd to wear just light white shawls.

In one corner of the health center, there is a small makeshift room made of poles of eucalyptus. It is one of the eight podoconiosis treatment centers that have been built in northern Ethiopia by the non-profit International Orthodox Christian Charities (IOCC). The non-profit sets up its treatment sites inside government health centers, and charges patients nothing.

Elderly men occupy the three benches inside the wooden room. Women sit on the ground. Most men are standing. The feet and legs of some are swollen more than others. Most of the people are wearing shoes, either ill-fitting or badly torn. One man has used thin, green plastic cords to lace his tattered shoes. After about an hour wait, four people from the IOCC enter the room and begin to unload cartons and blue and green plastic tubs.

One of the four thanks everybody for coming, and follows that with an apology. “We are sorry. We couldn’t get the shoes this time,” he says. The non-profit had earlier taken the measurements of the patients’ feet, to customize shoes for them, and had asked them to find something temporary to cover their feet until the shoes were ready. “There is a shortage of raw material and funds,” he says. “But don’t worry. We are getting them made for all of you. Your shoes are yours, and only you will get them. Please stay in touch. You have to be strong to be cured. You have to be patient. We have only six shoemakers, and a lot of people to treat. Don’t give up on wearing shoes.” He stops. Everybody claps.

“Don’t lie to me. You have worn shoes only today just to show me. I won’t be able to help you if you don’t take it seriously.”

IOCC trains local shoeshine boys to make customized shoes for the patients. But due to high demand, it provides shoes only once to each patient. Seifu Tirfie, the IOCC Ethiopian director, finds it disheartening when patients come back after their shoes wear out. “They ask for another pair, not because they don’t want to buy shoes [themselves], or don’t have the money, but because shoes suiting their size are not available in the market,” he says. Many patients have massive swelling, which takes time to subside. IOCC also distributes shoes from TOMS. In addition, Tirfie is now working out a deal with a local shoe company to open a factory in northern Ethiopia. The non-profit will create the demand for shoes by raising awareness, so that the company can sustain itself. “The idea is to introduce shoes,” says Tirfie. “The sustainable way is to make people buy shoes.”

Tigist Getaneh, the 26-year-old head nurse, enters the IOCC treatment room. She carries a bunch of green cards. Hair tied in a high bun, she wears a white coat over a yellow frill top and a brown-checked skirt. “Take off your shoes,” she says sternly. She looks at the green cards and calls out names, one by one. Meanwhile, her colleagues open the cartons.

The first name called is Tibeyn, a woman in her late 40s. “Show me your feet. Are you feeling better?” asks Getaneh, bending down. Her earrings, in the shape of a dancing girl, dangle over her shoulders. “I am getting better, but swelling is still there,” says Tibeyn. One man has an infected toe cleft. “Either you are walking barefoot or not washing your feet regularly,” says Getaneh. “You are cheating yourself. Don’t lie to me. You have worn shoes only today just to show me. I won’t be able to help you if you don’t take it seriously,” she tells him.

While some patients get their check-ups from Getaneh, the rest line up to get their feet measured. A woman wearing a white coat sits on the ground. She is holding a wooden footrest on which patients place their feet. She takes the measurements using a measuring tape, and notes them on the green cards.

Getaneh asks three patients to demonstrate the correct way of washing feet. Her colleague brings plastic tubs. Although still swollen and cracking at places, the feet of the demonstrators appear to be regaining shape. They put their feet in tubs full of water, lather their feet and legs with soap, massage for a few minutes, and wash them with water. Then they replace the dirty water with fresh water, and put in a few drops of bleach. They soak their feet in the tub for about 15 minutes, and then dry them with a clean towel. At last, they wrap bandages tightly over their feet, pull on long socks, and then shoes. Patients are supposed to repeat this procedure twice a day.

IOCC, which is headquartered in Baltimore, started working on podoconiosis in 2009. Since then, its funds for podoconiosis have grown from $60,000 in 2009 to $400,000 today. However, that is not enough to scale up its treatment program. About 20,000 patients are on a waiting list for treatment. “We are not sure if we would be able to treat all of them. Shortage of funds is our biggest challenge,” says Haregewoin M. Desta, senior program manager with IOCC, which has so far treated about 6,000 patients. Some of these have recovered nearly completely.

In a nearby town called Debre Elias, I visit Ayalew Mekonnen. My interpreter Girma and two IOCC members join me. As we approach Mekonnen’s hut, the yellow of harvested cornfields gives way to the green of freshly cut blades of grass that have been strewn on the mud to welcome us. His wife, Mubarak, greets us at the entrance, in a sky-blue pleated dress. She hugs each one of us and plants a kiss on our cheeks. Her two sons, in their 20s, hold our hands and lead us to a dim room inside.

A few old men, neighbors and relatives, are sitting in the room. Mekonnen’s sons drag plastic sacks stuffed with teff, a local grain, from a corner to the middle of the room for us to sit on. Fragrance from incense sticks wafts around us.

As we chat, eat, and drink, Mekonnen’s sons come in with a sheep. “They are going to slaughter it for lunch,” someone tells me nonchalantly. I ask Girma to tell Mekonnen that it is not necessary. Mekonnen tells him, “I am doing it out of love and gratitude for IOCC and the other guests. IOCC gave me my feet, my life.”

One of Mekonnen’s sons comes and stands in front of us. He is holding a piece of paper with a poem written on it. Mekonnen (who cannot read or write) dictated the poem to his son, who begins to recite it in the local language, Amharic. Everybody listens in rapt silence. In the poem, Mekonnen says that IOCC gave him new life. That he cannot return such a big favor. He prays to God to give long life, good health, and happiness to the people of the non-profit. As the poem finishes, the eyes of some well up. Mekonnen stares at the ground. I too feel a surge of emotion, even though I don’t understand the language.

Mekonnen grew up in a peasant family. From an early age, he had to work on the farms of others to make ends meet. His first marriage, at the age of 23, to a woman from his village, lasted only three years. “She left me,” he says. “She was unhappy because I could not provide for her.” One morning she went back to her parent’s home and never returned. Then, Mekonnen’s father died. He was left alone with his blind mother. “It was a tough time,” he recalls. Around the same time, Mekonnen’s feet began to itch.

It was after his marriage to Mubarak and the birth of their first child that Mekonnen started noticing the swelling in his legs. Gradually, the skin of his feet started to harden and turn mossy. Worried, he spoke to some educated people in his village, who told him that God was punishing him for something he had done. Mekonnen did not visit a doctor because people told him that the swelling was incurable.

His feet turned heavier. Lumps started to appear, first near the toe cleft, then near the ankle, then many more up his legs. Mekonnen folds his fingers into a fist to show the size of the lumps and places it over his feet saying, “Here, here, here, here, and here.” The lumps hardened. It became difficult to walk. Frequent pain made him bedridden for days.

A few months later, Mubarak left him, taking their child, to stay with her parents. Neighbors had already started to ignore him. One day, he trudged up a mountain with the thought of throwing himself off the cliff. Just as he was about to jump, the face of his blind mother flashed before his eyes. He says, “The thought of what would happen to her made me stop. I came back, walking with those unwieldy feet.”

It was another podoconiosis patient in his village, called Tete Tsenaye, who came to Mekonnen’s rescue. He told him about the IOCC treatment, and the two men walked barefoot, about 30 kilometers, to reach Debre Markos. There, the people at the non-profit gave them soap, bleach, Vaseline, and custom-made shoes. Gradually, the two men started to see improvement. The non-profit also helped Mekonnen get his lumps surgically removed in the Debre Markos Referral Hospital. His feet began to regain their normal shape. Now, whenever Mekonnen is in Debre Markos, he goes to the office of IOCC and kisses its walls. “That place is like church to me,” he says. “Today I walk with my head held high.”

Mekonnen brings out a pair of old, tattered, and oversized shoes. He dusts them off with his hands. “These were my podo shoes three years ago,” he says, sitting himself down on a eucalyptus log outside his hut. The shoes look at least three times the size of his feet today. Even though the shoes are useless to him now, Mekonnen doesn’t want to throw them away. “They remind me of my past,” he says. “Every time I see them, I think, how far I have come.”

Just then, a man walks into his hut. His toes are bulging. Nails have fallen off. There are cracks all over his feet. Their skin looks like sandpaper. Flies gather near the cracks. His feet and slippers are covered in red soil. He is Tsenaye, the man who told Mekonnen about IOCC. As he sits next to Mekonnen, I stop in the middle of a conversation staring at his feet. I take many minutes to regain my composure. Tsenaye’s feet, like Mekonnen’s, had been getting better with the treatment. But after his custom-made shoes wore away, he could not find shoes of his size in the market. His disease is now coming back.

Since funding from international organizations is tied to specific diseases, the governments of endemic countries are usually obliged to use the money only for those. Abdurahman thinks that international money does help, but he also has a problem with it. “A community does not choose this disease over that disease. If you ask a community affected by Kala Azar, they will say Kala Azar is a problem. If you ask a community affected by podoconiosis, they will say podoconiosis is a problem. I don’t understand, then, how can you choose one over the other,” he says.

Whenever Abdurahman gives a presentation on neglected tropical diseases, he tries to include them all. Implementation of drug-based diseases is simple, he says. “I say, please support other diseases too, but nobody listens and they say, we are sorry,” says Abdurahman.

Biruk Kebede, director of an Ethiopian non-profit called National Podoconiosis Action Network (NaPAN) has similar stories to tell. In December of 2014, the World Health Organization participated in a meeting on neglected tropical diseases. The meeting was happening in Ethiopia. But podoconiosis was not on their agenda, says Kebede. He has asked many international donors to fund podoconiosis, but in vain. “It’s frustrating.”

It is hard to convince people to wear shoes.

Emily Wainwright, team leader of neglected tropical diseases section at USAID, says the five diseases that USAID funds were chosen in part because they can be targeted through mass drug administration. “It is a good focus. But,” she adds, “that is no consolation for people suffering from other diseases.” “My heart goes out to the neglected of the neglected,” says Ellen Agler, Chief Executive Officer of the New York-based non-profit End Fund. “But right now we are trying to address those for which we have solutions.” End Fund sources money from philanthropists to target the same five diseases as USAID. “We don’t even have enough money for these diseases,” Agler adds.

Abdurahman believes that for podoconiosis to get the international attention it needs, regional governments, including his own, will have to take charge. “Donors need numbers. We need to analyze the disease burden in other endemic countries also,” says Abdurahman.

Or a celebrity could help. Peter Hotez, a dean for the National School of the Tropical Medicine in Houston, gives the example of guinea worm disease. In 1986, when former United States President Jimmy Carter decided to advocate for the disease, it afflicted 3.5 million people in 21 countries across Africa and Asia. A neglected tropical disease, it is caused by drinking stagnant water contaminated with guinea worm larvae. The Carter Center led an international campaign to eradicate the disease. Last year the number of known cases was down to 126. “Believe me,” says Hotez. “Had it not been for President Carter, guinea worm would have been in the same place as podoconiosis.”

There is a crucial difference between podoconiosis and most of the other diseases on the USAID list, or even most other neglected diseases. It needs behavioral change, rather than drugs. “That is a different kind of public health problem,” says Wainwright. It is hard to convince people to wear shoes.

A few minutes after Mintamir’s lunch, a woman walks into her hut. Yitayish Bekele, Mintamir’s sister-in-law, is barefoot and carries her 8-month-old child on her back covered with a green shawl. She is the only person from the neighborhood who visits Mintamir regularly. As they make coffee and chat, one of Mintamir’s daughters, Netsanet, runs in and out of the hut. She is wearing a bright blue frock and matching blue plastic shoes. After a while, when Bekele is getting ready to leave, I ask her why she goes barefoot. “I don’t like to wear shoes,” she replies. “My feet are fine.” Bekele thinks Mintamir’s condition is a result of witchcraft, and cannot be cured. Many in the neighborhood have asked Bekele to not visit Mintamir, as she may also get the disease. “She is my relative. I cannot see her suffer in that hut,” says Bekele, walking off toward her own hut. She wouldn’t visit if Mintamir were not her relative.

In another hut not far from Mintamir’s, two women are chatting. One of them is barefoot. I ask her why. “I have to do a lot of work. Walking with shoes is uncomfortable,” she says.

Even many around Mekonnen, who has recovered from the disease with the help of shoes, continue to go barefoot. At Mekonnen’s hut, I try to talk to Mubarak, his wife. It is hard to get her to sit and talk. She is always busy doing something or other. She cooks, collects firewood, draws water, grinds corn, or puts the house in order. At night, it is dark inside the hut, as the village doesn’t have electricity.

I finally catch up to her the morning after our meal. She is preparing injera in the smoky hut. At my insistence, she sits down, restlessly, in the doorway. Mubarak’s hair is cropped short, like Mintamir’s, and she has a similar tattoo decorating her jawline. She is in her early 40s but looks much older. Wrinkles have gathered near the corners of her eyes. Her blue pleated dress is soiled with dirt and patches of teff paste.

I ask Mubarak about the days when Mekonnen had big feet. She looks away. No words come out. She picks up a stick, and starts scratching the ground. It seems she does not want to talk about it. She gets up, and goes inside the hut to check if the injera is ready. It is. She starts making another one. “How was it before,” I ask Girma to repeat.

Now she sits as if under an obligation to talk. “It was hard,” she says after a long pause. “Hearing him howl every night in pain … was hard,” she continues. “We rarely ate dinner … did not feel up to it … His cries still ring in my ear … My children were scared … I was scared … some nights, I wanted to leave,” she says while reaching out to touch the back of her neck with trembling fingers.

Despite her husband’s experience with the disease, Mubarak doesn’t wear shoes. Nor do any of her children, as they walk around the hut, or outside in the red soil. Only Mekonnen wears shoes. “Why are you not wearing shoes?” I ask Mubarak. “I don’t have,” she says. “He never got me.”

Mesgana, Mekonnen’s 9-year-old daughter, has oversized shoes that Mekonnen brought her. But she doesn’t like wearing shoes. Her brothers feel the same. When I ask them if they know what causes podoconiosis, they stay silent. But they do realize that shoes are important in curing it, after observing their father over the years. I ask Mekonnen, why didn’t you buy shoes for your wife and children when you know the importance of shoes? Why don’t they know about the cause of the disease?

He has no answer. He stares at the ground.

Ankur Paliwal is a journalist who writes on science, health and the environment. He is currently based in New York.