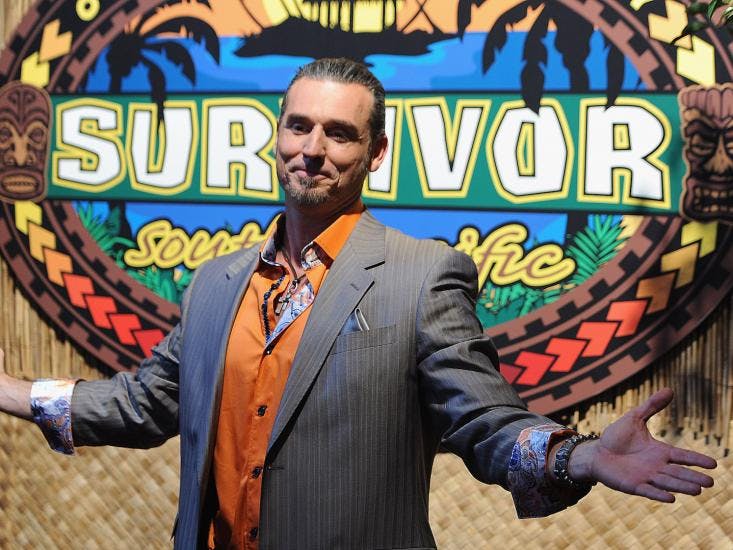

Exactly four months and 31 days into what was, at that time, still being called “The New Millennium,” CBS aired the first-ever episode of Survivor. Bill Clinton was still in office, the NASDAQ Composite Index had just peaked at 5,048, and the twin towers still stood in New York City. Since then America has seen two wars, two presidents, an economic recession, the rise of the smartphone, the death of Boy Bands, and 30 more seasons of Survivor.

Since its inception, the show has consistently been #1 in its time slot. Fifty-two million people watched the first season finale—as many as watched the series finale of Friends. Survivor’s numbers have slowly tapered off since then, but they’ve been holding strong for several years at around 9 million, outlasting virtually all its reality-TV offspring and suggesting that Survivor is down to a loyal, core audience—many of whom find each other online. There are still highly active message boards and forums where users debate the tactics of each contestant, cheer for their favorite, and analyze the show’s editing for hints at who might become champion.

Who are these 9 million people—and why do they care?

Back in 2004, the year of Survivor: Vanuatu and Survivor: All-Stars, Ohio State University clinical psychologists Steven Reiss and James Wiltz became intrigued by the reality-TV phenomenon, so they decided to parse why people were watching these shows.

Reiss relied on a comprehensive theory of human motivation he is well known for developing, which asserts that all desires can be placed into 16 categories. Curiosity, for instance, is the desire for knowledge; eating the desire for food; independence the desire for autonomy. The idea, known as sensitivity theory, maintains that different people are more or less motivated by certain desires; As Reiss and Wiltz put it, “People pay attention to stimuli that are relevant to the satisfaction of their most basic motives.”

To understand why people watched reality-TV shows—specifically Survivor, Big Brother, Temptation Island, The Mole, and The Real World—Reiss and his colleagues investigated which of the 16 basic desires were the fiercest in reality TV viewers. “You would look at what values are being expressed and projected [in the show], and then like-minded people would constitute the natural audience,” Reiss explains.

After asking 239 adults how much reality-TV they consumed and how it made them feel, he found that people who watched more reality-TV were significantly more motivated by “status” and “vengeance.” In his analysis, Reiss found that the more motivated people were by these two desires, the more reality-TV they watched.

Perhaps it’s vengeance that keeps the core Survivor audience hooked.

The finding that “status” was the number one motivator in reality-TV viewers was surprising to Reiss at first, but it began to make sense the more he thought about it. “The whole idea of reality-TV is to put ordinary people on TV,” he says. “Attention to ordinary people is basically a statement that ordinary people are worth paying attention to.”

According to Reiss, Survivor tapped into a demographic that loved the idea of elevating the status of normal people. There’s a temptation, then, to argue that the show owes its success to the same sort of demographic that kept 16 and Pregnant afloat for five seasons and enjoyed the Newlyweds, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, or The Real Housewives of Miami. All of those shows made ordinary people into stars, but they’re also dead.1 Survivor isn’t.

Perhaps it’s that second desire—vengeance—that keeps the core Survivor audience hooked.

The only person I know who still watches Survivor is my friend Nick. He’s seen all 30 seasons and possesses amazing recall of each one. He is also the editor in chief of an award-winning national magazine. At just 28 years old, his rise has been swift, but hearing him describe it also leaves you with the impression that it has also been exceedingly calculated; he loves the maneuvering and strategizing, and he’s proud of the fact that he finessed his way to the top so quickly. “I think I’m good at playing the political game,” he says. “Yes it’s totally manipulative, but I don’t want it to seem like that’s a bad thing. I think it’s for an ultimate good cause.”

When I ask him if he sees parallels of the show’s competitiveness in his real life, he immediately answers, “Yes. I mean, absolutely yes.” In an effort to understand the show’s appeal, I made him walk me through Episode 4 of the most recent season. This turned out to be a huge mistake, because now I’m addicted to Survivor.

What I quickly became convinced of is that the show is actually a full-fledged masterpiece. Every episode is 43 minutes of tightly crafted drama. In Episode 4, it came down to Jeff Varner or Woo Hwang up for elimination. Hwang had a history of trying to vote his tribe mates off, but Varner was injured, making him less valuable in physical immunity challenges. That was enough for Angkor tribe: They voted Varner off, sparing Hwang for his physical utility. Plus, since he’s now the clear low-man on the Angkor totem pole, he’ll probably be more motivated than anybody to win those immunity challenges.

Everybody says Survivor spawned reality TV, but at its core, Survivor is just a complex, compelling social strategy contest held in front of a camera; it’s not pretending to mimic real life, and that gives it a sense of honesty and credibility. “Clearly they’re surrounded by cameras and producers and people running around, but I’m pretty sure for the most part they’re kind of just left alone,” says Nick. “I feel like it’s pretty real.” This approach contrasts with say, The Bachelor/ette shows, which try to minimize the contest and put the resultant drama first: Survivor is more Price is Right than Flavor of Love.

Nick tells me that if he were on Survivor, he could win. If he’s at all representative of the loyal fan base the show still has, then it seems to me that Survivor owes its longevity to the Nicks of the world—the unrepentant schemers, who value social manipulation and winning not just on TV, but in their lives.

Footnote

1. The irony of referring to Mama June et al. as “ordinary” is not lost on the author.

David Shultz is a freelance journalist covering biology and science of all sorts. @dshultz14