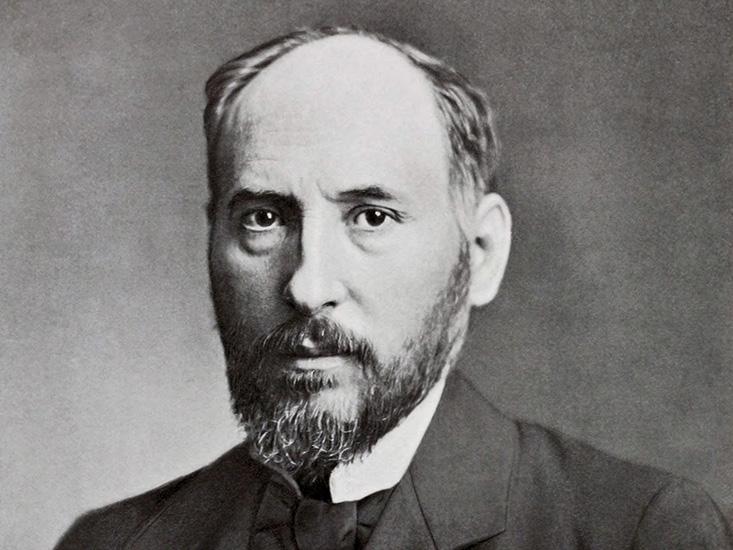

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish histologist and anatomist known today as the father of modern neuroscience, was also a committed psychologist who believed psychoanalysis and Freudian dream theory were “collective lies.” When Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, the science world swooned over his theory of the unconscious. Dreams quickly became synonymous with repressed desire. Puzzling dream images could unlock buried conflicts, the psychoanalyst said, given the correct interpretation.

Cajal, who won the 1906 Nobel Prize for discovering neurons and, more remarkably, intuiting the form and function of synapses, set out to prove Freud wrong. To disprove the theory that every dream is the result of a repressed desire, Cajal began keeping a dream journal and collecting the dreams of others, analyzing them with logic and rigor.

Translated here into English for the first time, the dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal offer insight into the mind of a great scientist.

Cajal eventually deemed the project unpublishable. But before his death in 1934, he gave his research, scribbled on stained loose papers and in the margins of books and newspapers, to his good friend and former student, the psychiatrist José Germain Cebrián. Germain typed the diary into a book, which was thought lost during the 1936 Spanish Civil War. In fact, Germain carried the manuscript with him as he traveled through Europe. Before his death, he gave it to José Rallo, a Spanish psychiatrist and dream researcher. To the delight of scholars and enthusiasts, Los sueños de Santiago Ramón y Cajal was published in Spanish in 2014, containing 103 of Cajal’s dreams, recorded between 1918 and his death in 1934.1 Translated here into English for the first time, these dreams, and Cajal’s notes on them, offer insight into the mind of a great scientist—insight that perhaps he himself did not always have.

Cajal exalted rational thinking and the conscious will. In his autobiography, the scientist described neurons as “mysterious butterflies of the soul, the beating of whose wings might one day, who knows, reveal the secrets of mental life.” He had a lifelong fascination with dreaming and dreams, despite, or perhaps because of, their tendency to resist all rational explanation. Early in his career, Cajal studied hypnosis and the power of suggestion, turning his home into a clinic for hysterics, neurasthenics, and spiritual mediums, and he planned to publish three psychological books before judging their content to be too speculative: Essays on Hypnotism, Spiritualism, and Metaphysics; Dreams: Critics of Their Explanatory Doctrines; and Dreams. He did, however, publish a scientific paper in 1908 on dreaming and visual hallucinations, which begins, “Dreaming is one of the most interesting and most wondrous phenomena of brain physiology.”2 He investigates visual hallucination in blind adults, concluding that the retina is not active during dreaming, instead studying the associative cortex, thalamus, and glial cells for evidence of activation.3

In 1902, in the preface to a contemporary poetry book, the normally reserved Cajal allowed himself to theorize a bit more freely about dreams. “The majority of dreams,” he writes, “consists of scraps of ideas, unconnected or weirdly assembled, somewhat like an absurd monster without proportions, harmony or reason.” He theorized that dreaming happens in unused areas of the cerebral cortex: “The fallow lands of the brain, that is, the cells in which unconscious images are recorded, stay awake and become excited, rejuvenating themselves with the exercise they did behind the back of the conscious mind.” At the end of the waking day, according to Cajal, certain groups of cells are tired out, leaving others to work during sleep. More than any theory, this persistent cellular focus is Cajal’s legacy to psychology, which indeed now favors a neurobiological approach.4 Some contemporary theories about the neuroscience of dreaming, namely the activation-synthesis hypothesis, would seem to support Cajal’s belief that dreams are a sequence of random images, unfiltered by the prefrontal cortex, which the brain then tries to interpret.

Cajal’s anatomical views on dreaming and his reluctance to speculate without physiological evidence stand in stark contrast to the dream theory made famous by Freud. In a letter to Juan Paulis, published in 1935, Cajal wrote, “Except in extremely rare cases it is impossible to verify the doctrine of the surly and somewhat egotistical Viennese author, who has always seemed more preoccupied with founding a sensational theory than with the desire to austerely serve the cause of scientific theory.”5

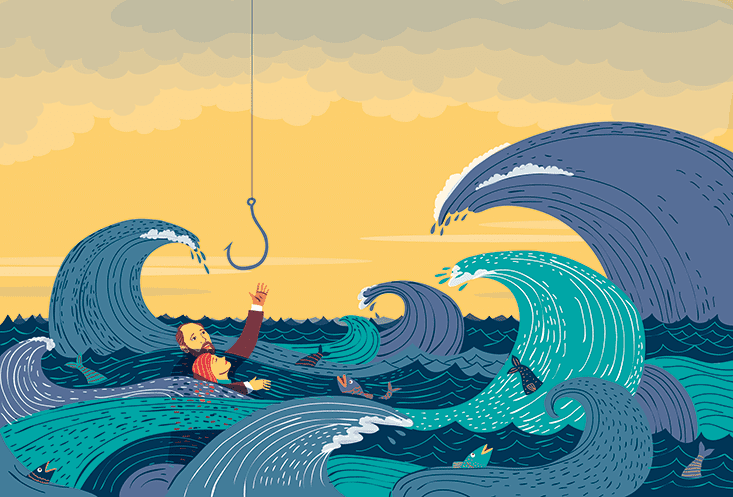

Devoted, like many mythologized geniuses, more to his work than his family, Cajal remained entranced at his microscope, failing to respond to his wife, Silveria Fañanás García, as she screamed through the night that their 6-year-old daughter was dying. In mourning, the light of the microscope was his only refuge. Thirty years after the death of his daughter, the father of contemporary neuroscience dreams that he is drowning off the coast of Spain, holding his little girl in his arms. This dream needs no further analysis.

In the transcribed manuscript, [——- ] indicates where Cajal left a blank space in his original notes, while indicates where he crossed something out.

A Common Dream

[Falling of pants]

I attend a diplomatic soiree and as I am leaving my pants fall down (Is it desire?)

[Drowning with daughter]

I take a walk by the bay (Santander?) and I fall into the water with one of my little daughters in my arms. I fight the waves, I am almost drowning, despite touching the seawall. The nightmare awakens me.

Morning Dream

[Declaration on the nature of humanity]

12 December 1926

After lecturing from the podium on who knows what philosophical subjects. I find myself amongst friends. The question of what constitutes human nature is raised, I do not know how. Without allowing anyone else to speak in an authoritative tone and capturing the attention of my listeners—all friends and colleagues—(I hear myself proclaiming vehemently), I declare that the doctrines [———] of the unity of the human individual are an illusion, that in reality there are four men inside of us:

1. The gangue man, the cellular cadaver, the connective tissue, bone , intercellular materials X. It is the stuffing of life. Strength of stature is the façade and the plaster of the building.

2. The glandular and sympathetic man, that is to say, the set of internal and external secretory organs, coordinated by the sympathetic ganglia, governing vegetative life and controlling the higher individuals (emotional, synaesthetic) and the gangue man.

3. The pneumonic and conscious man, that is to say, the cerebral nervous system, the registry where sensory residues are stored. It is joined to the exterior world by the senses and to the higher self by certain cerebral pathways. This self can be conscious (sensation, perception) however it generally remains as a storage space for primary ideals (the “unconscious” of many authors). It produces the reflective and intuitive moment. The higher self is that active, imperious, conscious impulse, the selector that consults the files of the cerebral library, that [——- ] the pathways, decides on useful and deliberate reactions; attends, or not, to sensation; represses reflexes, moderates instincts and forges ideas and theories by changing the sensory material of the mind. This self , that sees but is not seen, that in the dream state (hallucinatory orgy of the secondary self, fed up with contradictions says: Enough; all of this is an illusion, let us awaken. Believing that a representation is the self is like thinking that a photographic lens portrays itself. It would be possible if there were a mirror opposite. But in man there is no mirror of the self. The self is absolutely inaccessible. That which we take for a mirror, consciousness, only shows us the product of the [——] selection, thought to be the object, but what is thought to be the object is not what we think, but rather another part of the images about which one thinks …

The self is an energy, an invisible pull like a god …

Here I awaken.

Dream of the Printing Press

[Proofs of the book on regeneration]

I find myself at a printer correcting copies of a book about regeneration. I discover that there are many letters missing, that prepositions are absent, and that syllables have run from one line to another. I am astonished and ashamed by all these errors.

Inconsistencies. I am not correcting book proofs during the course of the printing process, but rather a book that is printed and already for sale, and also translated into English. There is no point to my corrections, then. Moreover, the book, of which I do not desire to produce a new edition, was printed 12 years ago. I awaken.

Strong headache due to the stifling heat I feel while checking the errors, which are now unavoidable. I am in Jaca.

This cannot be explained by Freud.

There is nothing here but a reminiscence of a previous act with distortions.

I imagine that I am at Pueyo’s press, where the book was not made. New inconsistencies.

Dreams (In Sigüenza)

[Class in Osteology]

I am an assistant professor. Suddenly I receive express orders from the dean to teach osteology at the very last minute. Anxiety, anguish when going over the bones in my memory. I enumerate those of the hand: scaphoids, capitate, and I did not know any more. Meanwhile the class awaits me, the students yell. I ask to myself how I will lecture about bones if I have almost forgotten them? Growing anguish and I awaken with a sense of well-being, upon realizing that I am not a professor, I am old and no one is directing me.

Inconsistencies:

1. Imperiously demanding that a 77-year-old retiree lecture on osteology.

2. Neither poor health nor lack of time to prepare occurring to me as possible excuses.

3. Forgetting things that I knew; when I wake up, I recite the carpal and tarsal bones from memory without mistakes.

(Obstruction of the mnemonic centers).

Antecedents: For 50 years I was an assistant professor and taught anatomy and other subjects for the Dean (Zaragoza) and then the Chair of Anatomy in Valencia. But I received the teaching assignment a day in advance which allowed me to prepare myself.

Strange that even though I learned all the details of osteology from my father from the ages of 12 to 15, they saw me stuck on things that I still know. It is, then, an inaccurate and fragmentary evocation of remnants of facts with distortions of the same, since if I had been asked to lecture on bones when I was an assistant, I would have been able to do so passably and with no need for preparation.

Where is the repressed desire? I do not see it. The desire was fulfilled 50 years ago and now I have other preoccupations. The dream, then, is a fragmented and distorted evocation of some painful scene in my life as an assistant when I had to teach lessons in surgical or medical Pathology with little preparation, not in Anatomy which I knew well.

Daydream

[Arrogantly battling wounds]

26 May 1929

Before the veronal and before 3:30.

Goes fast. Does it take place in the great hall of a theater?

I enter a hall where apparently there had been a war between liberals and reactionaries. Before entering, in a kind of foyer, I find various wounded people amongst others who boast a frontal bullet wound and Lafora walks by saying, I have a serious wound. He does not wear bandages. Unarmed, I enter the great hall, where shots are heard. Some enemies see me, but they do not shoot from the side where I am. Someone from the other side says: go, so that nothing happens to you. I, very arrogantly, answer shoot all you like, that at most you will cut off only a few months from my life. But they do not shoot. They say that it is not worth the trouble. In light of this I leave. The emotion awakens me.

It seemed more like target practice than a battlefield. Nothing was forcing me to go in. And it seemed that the fight was of a political nature and was kept up between liberals and reactionaries.

Completely absurd. I did not see any dead people.

Causes: Having read earlier in the day about the death of Enrique de Mesa from an embolism. The execution of a student who tried to kill Valdemoros (Finland?). I do not understand it. I do not talk to anyone. During the day my activities have been peaceful; went by automobile to my orchard to pick sour cherries.

Inexplicable. I fell asleep reading a book [——] by Julio Camba. I see no signs of repressed desire.

Granddaughter

House of wild animals. Various wild animals ate her. I do not live.

—-

The bull had to go through a field and as he passed by, he grabbed hold of your head and bit into it and later it turned out that he had buried the head under a pillow.

—-

A girl playing and they gave her a shove and she fell down a steep hill. It startled her.

—-

She broke the head of a very beautiful doll and substitutes it for the head of a ragdoll that she painted eyes and a mouth onto. It was very ugly, but she liked it better.

—-

Thieves break in. And I said to them: do not kill me, and they took out a revolver but later it turns out it was only a toy just to frighten me.

—-

In school the desks were converted into beds and you slept there. Visitors came and they gave you food. The teacher brought them chocolate.

—-

Cannibals. You were on an island and some black cannibals jumped out and they put you on the grill and poured oil on you. You, so peaceful. They ate you and they reported saying that the meat was hard and had to fatten more.

—-

A movie theater in a church. And with a ray of light through the roof I could see skulls and skeletons. Ignore more. The movie theater was a thing of the priest.

Terrible Dream – Tactile Dream (evening of Espronceda)

[Brain in the hand]

I dream that they remove my skull and that there is only skin covering my brain. I feel the contact of brain with skin and its weight falling to one side, I hold it there with my hands, waiting for the doctor who will make a protective cap for me out of who knows what. I think it very natural that they have removed my skull and I’m reminded of another dream about the same thing in which my skull grew back and the vault was consolidated. I do not understand the operation, and I think it very natural for it to be done and that the brain is covered with skin without further precautions. I go for a walk around the room and am alarmed and awaken when I see that my brain is falling out. (The scene happens in the house on the street where Zaragoza Hospital is). My wife is alarmed.

(I have dreamed this other times). It is surprising to walk and not fall, into a fit. My hands placed on my head touch something smooth that moves. I alert my wife who does not know what to put on me; I am missing my discarded skull. It is an operation that I consider to be ordinary and natural. Anguish in the end and I awaken. I want to try to touch, but I cannot get to anything before I awaken.

Antecedent, having seen the brain during autopsy? I do not believe that having seen a trepanation years ago (was it on the skull of Espronceda? Theory of the retina impossible here.

They are emotional dreams, they do not lend themselves to explanation. They awaken me right away.

Dream

[Meal with engineer’s wife]

I am invited to the house of an engineer. His wife watches me eat heartily. She is surprised and congratulates me because she had heard I was sick and on a diet and was eating very little. We talked about her husband, a man from the staff of the school whom I did not know. A regime of unknown faculty and I say sensibly: excuse me, I hardly know the professors from the school of civil engineering.

Inconsistencies: for many years I have not eaten outside the house. I do not know the wife of any engineer intimately enough that they would invite me to eat.

—But one would say, V. is sick, V. usually has no appetite. Eat well, V., and thus his dream is the fulfillment of desire.

But in my dream there is no element of [———] that can be interpreted by Freud. And the rest, the distressing ones? Shall we appeal to unconscious memories? But this destroys the hypothesis of Freud. Whether or not they arrive at distressing scenes from the past, here there is no fulfillment of any desire. And one would have to be very subtle and very specious in order to see a realized desire in 80 out of 100 of my dreams.

Other times I teach a lesson or give a conference.

Desire? None. It is work and in my situation more. It is an acquired habit that has not been carried out for 5 years. Would I desire to carry it out? No.

But even if it were true it would better fit with my hypothesis. The cerebral cells inclined to this task are resting, are oversaturated with sensory, motor, and ideal memories and they are unburdened of their excessive stimulation. Let us not forget the perfect logic of these conferences.

Ben Ehrlich is a writer living in New York City.

References

1. Velayos-Jorge, J.L., et al. The neurobiology of sleep: Cajal and present-day neuroscience. Revista de neurologia 37, 494 (2003).

2. Rusiñol Estagués, J. & Ibarz Serrat, V. La recepción del pensamiento de Freud en la obra de Ramón y Cajal. Persona 6, 75-80 (2003).

3. Lopez-Muñoz, F., Alamo, C., & Rubio, G. The neurobiological interpretation of the mental functions in the work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. History of Psychiatry 19, 5-24 (2008).

4. Rallo Romero, J. Los sueños de Santiago Ramón y Cajal Editorial Biblioteca Español S.L., Madrid (2014).

5. Ramón y Cajal, S. Las teorías sobre el ensueño. Cajal. Revista de Medicina y Cirugía de la Facultad de Madrid 3, 87-98 (1908).