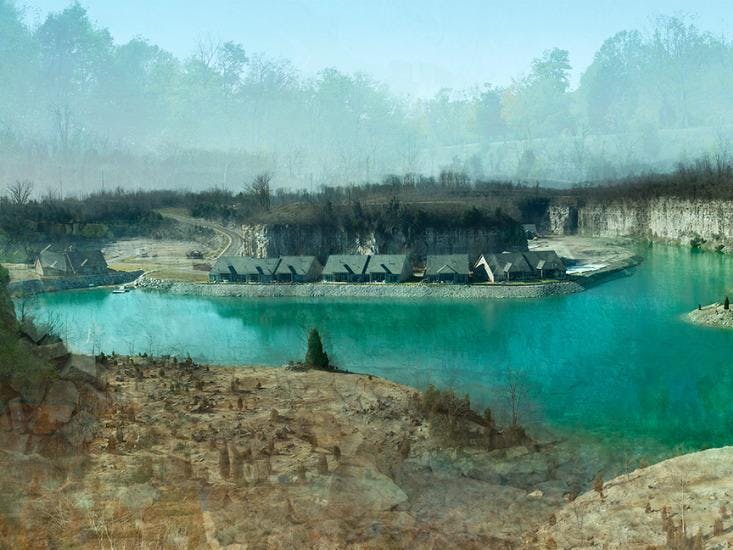

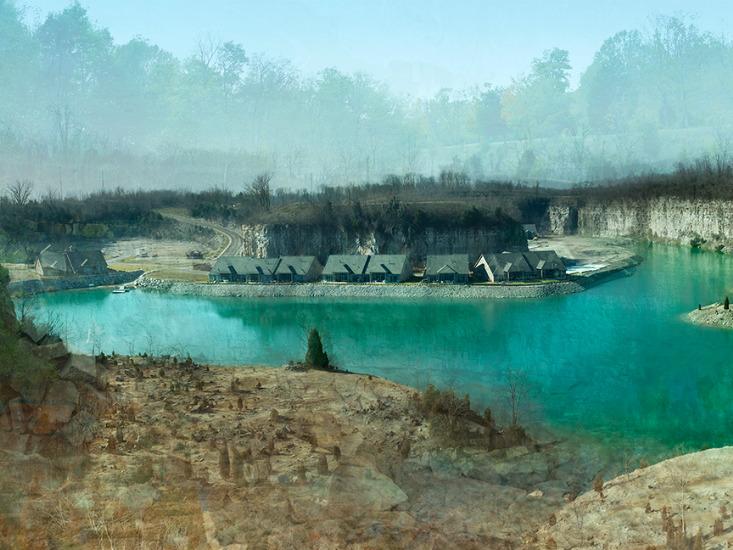

There was a place in Iowa in 1995, tucked away in the dark-green fields of soybeans and corn, where a flooded rock quarry shimmered aquamarine. I stood on its edge one hot summer day with two friends. Like most teenagers, we were drawn to the rebelliousness of it. To get there, we had to trespass on private land and ignore the “swimming forbidden by law” signs. But really, we wanted to experience something that we had only seen on postcards. “It was a beautiful oasis,” remembers one friend. “Like lagoons in Hawaii,” recalls another.

We removed our shoes and chose a low point of entry. Our bare feet crumbled the soft limestone composed of brachiopods, crinoids, and trilobites, ancient creatures that once lived in the shallow seas covering Iowa millions of years ago. (The geological twist being that the state is now landlocked, and these remnants of its prehistoric sea life pave the local secondary roads.) We jumped in.

We weren’t the only ones drawn to forbidden blue water. Open-pit quarries exist in many rural regions of the world, and they often entice swimmers who don’t have easy access to the sea. But quarries are sometimes toxic and even deadly. One rock quarry in the countryside of England was called the Blue Lagoon, but it was full of trash and had a pH value similar to bleach. The local government posted signs, warning of the water’s toxicity, but that didn’t deter swimmers. People stopped coming to its shore only after officials dyed the water black.

So why does blue water have such a draw on our psyche?

Maybe it is the promise of fish. Scientists are looking into how a seafood-based diet is critical to brain development. The brain needs high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids and other nutrients such as iodine and zinc, which we get from fish, mollusks, and crustaceans. A 2014 study posits that early humans lived near the shore with access to these nutrients, because it’s the clearest explanation for the rapid increase in brain development that followed. “What would be the advantage of being near water while evolving?” asks Stephen Cunnane, an author of the study. “We must have been eating more fish, not just for the omega-3, but for the iodine and zinc and iron as well—a cluster of brain selective nutrients that helped the brain grow.”

Cunnane says that 2 million years ago, early hominids fished the lakes of East Africa. Eventually some humans migrated to the coasts and mastered saltwater fishing, which was trickier because saltwater fish are faster, but also more rewarding, because they have more iodine than freshwater fish.

Research by Karen Schloss of Brown University and Stephen E. Palmer of the University of California, Berkeley suggest that part of the allure of some dangerous quarries is, in fact, their blue color. In multiple studies on how people feel about colors, the psychologists discovered that a person’ preferences are determined by cumulated experience, which forms positive or negative associations for particular colors. “For blue, most of the things that we associate with it are positive,” she says, including clear skies and clean water. Schloss found this to be the case in the United States, Japan, and China. In their U.S. study for example, 72 participants were shown a color on a neutral background and were asked to write as many descriptions of objects that were typically associated with the color before them. Then 98 different participants were shown each of the 222 descriptions written in black text on a white background, and they were asked to rank how positively or negatively they felt about each. Finally, 31 new participants were shown the color along with the associated description, and asked to rate the strength of the match between the color and description. Schloss and her colleagues found a strong, positive association between blue and clean water. Other studies support this finding. A 2013 study found major cultural differences in the color associations among the British and the Himba, a semi-nomadic group in Namibia. Yet these groups still associated blue and clean water. Schloss cannot say whether these preferences are innate or learned, but they seem to be common across cultures.

The water felt slightly thicker than usual, perhaps heavy from sediment, and it passed over our bodies like silk scarves.

But not all water that is blue is clean, and the Blue Lagoon is a vivid example. Even the brilliant blue water in the Iowa rock quarry that summer day didn’t look potable, and if we were drawn to it because of a strong association of blue with clean water, then it must have been subconscious. Schloss, however, offers another interpretation. “It’s possible that if you had seen pictures of that and you associate that color with the Mediterranean Sea, then that would inform your preference for the color, because then that particular color in the context of water is associated with a tropical vacation in paradise.”

Back at the rock quarry in Iowa, as we entered the water, we kept our heads just above the surface, inhaling sharply from the exhilaration. The water felt slightly thicker than usual, perhaps heavy from sediment, and it passed over our bodies like silk scarves. As we pushed from the shore to the center, treading 40 feet above the bottom of the quarry, the water became colder. We looked back and saw a trail of decomposing leaves and large, gray clouds of sediment billowing out behind us in the water. Just then the fun started to fade, as we thought of what horror might await us there in the water. Getting snagged on a rusted tractor? Toxic chemicals? We quickly swam back to shore, laughing as we lifted ourselves out, happy to be free of whatever dark fate we’d escaped. The quarry looked better from the edge when we weren’t stirring up the water, and our anxiety lifted as we watched the pale-gray clouds slowly settle and give way once again to a pleasing aquamarine.

Regan Penaluna is a journalist who lives in Brooklyn.