In the 1930s, Russian-born sculptor Naum Gabo started experimenting with a thin, plastic material called celluloid. Previously used as film for photography or to make cheap jewelry, celluloid in Gabo’s hands became translucent geometric structures that were often suspended in mid-air. Art critic Herbert Read wrote that Gabo was using “new materials…[for] a new generation to create with them the monuments of a new civilization.” His pieces made their way into the top art collections in the world.

But by 1960, the plastic had begun to warp and crack. Gabo didn’t know it when he started using celluloid, but it is an extremely unstable and reactive material, and was infamous for catching fire in movie theaters. Despite conservators’ diligence to try to preserve his works, the plastic became too brittle and the sculptures collapsed. Gabo himself called many of them irreparable.

Gabo’s is a cautionary tale in art conservation circles; contemporary artists are more interested in experimentation, getting the right effect with a new or offbeat material, than how that material will look decades later, says Albert Albano, the executive director of the Intermuseum Conservation Association.

Though we’ve all heard about modern materials that will long outlive us in landfills, like plastic or Styrofoam, many artists are surprised to find that many objects found in stores won’t last mere decades, even under the controlled conditions in galleries.

“People often assume that modern materials are wonder materials, Space Age materials that will never degrade,” says Gregory Smith, senior conservation scientist at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. “But for many of them, the advantage is that they actually don’t last forever. If an artist is using shopping bags as part an art installation, for example, the person who made them may have intentionally engineered them to fail so we don’t have a world littered with shopping bags,” Smith says. If the plastic bag manufacturer added starch to accelerate the degradation of the plastic, that may help the bags degrade before they clog up rivers, but it may not be ideal as an artistic medium.

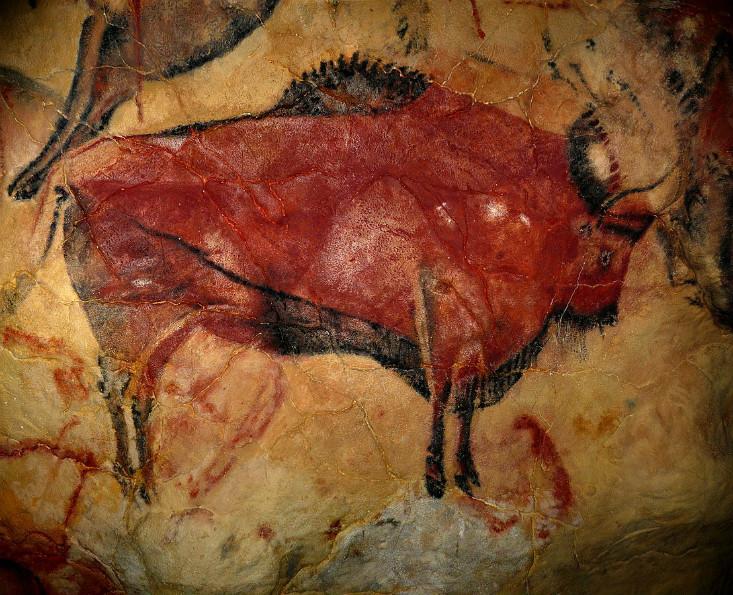

When artists are thinking on the timescale of centuries and millennia, they should instead turn to materials used by some of the world’s earliest craftsmen: stone and metal. From Roman statues to Hindu temples, Egyptian tombs to the first human cave etchings, objects made of stone can easily last centuries, often millennia if the conditions are favorable. Marble and granite tend to hold up better than sandstone. Metals can be a bit more “iffy,” Smith says; some objects made of copper and bronze date back to 6,200 BCE, but others rusted or corroded after just a few decades if they were exposed to too much water.

Art can be destroyed or warped by a huge number of environmental conditions—wind erodes stone, too little humidity causes wood to crack, light fades pigments. Today we can only appreciate cave paintings created more than 40,000 years ago because the conditions inside the caves were perfect for preserving them. Art conservators like Smith take great pains to ensure that each piece is preserved under the right conditions for the material’s chemical makeup.

But biological materials have proven surprisingly durable. “Wood, rabbit-skin glue, and oil paint have certainly stood the test of time,” Smith says, though their timeframe is often centuries, not millennia. Medieval panel paintings once wrenched from church altars and strapped to the back of conquerors’ horses are still on display at The Met; 12th-century depictions of Russian saints made of egg-based paint can be found today in Moscow galleries. Though some of the oldest pieces of art in the world are made of ivory, it’s very sensitive to changes in humidity, so its durability can also be hit or miss.

Some modern materials are just as durable as wood or stone, though not as many as one might think. Silicones, like those used to caulk windows or coat electric wires, and epoxies used as adhesives are quite good, Smith says. Conservators still don’t know how some new art materials—like dibond, used previously in outdoor signage, or acrylic paints—will hold up over decades and centuries, but they seem promising.

Of course, not all art is meant to last. “Take dance or performance art—it’s essentially ephemeral,” says Mark Tribe, an artist and fine-art professor at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. Photos, videos, notes, or other types of documentation help museum curators and other artists understand these transient pieces after they have evaporated in time. For these works, there are three very different preservation tactics: emulation (think of an early PacMan game that has been appropriated to run on a modern PC), re-creation (artist Marina Abramović’s pieces of performance art presented by others at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010), and reproduction (saving the now-obsolete closed-circuit TVs used in early new-media pieces).

Conservators like Smith are careful not to tell artists how to make their art more durable; the most important aspect of art is the idea behind it and finding the right material to match. “You [artists] make your art—our job is to make it last,” Smith says. But artists thinking on the time frame of centuries do well to consider the chemistry of their materials. It could make the difference between a masterpiece prized by future generations and one lost to the ages, like Gabo’s celluloid sculptures.

Alexandra (Alex) is a science writer. Currently based in New York City, she has previously lived in Brattleboro, Vermont; Lima, Peru; and Washington, D.C. She tweets at @alexandraossola.