Earth is on the brink of a mass extinction—the first in 66 million years, and it’s caused primarily by human activity. Scientists first detected this epochal event by calculating diversity in our forests and taking the temperature of our atmosphere, and they now outline steps we must take to deter the grim global prognosis. Engineers, following suit, have suggested ways to change human industry to reduce our footprint and try to soften the damage done. Ideally, politicians react, too, transforming scientific insight into Earth-friendly leadership.

But what’s the part of the professional painter or sculptor? In the presence of environmental anxiety, what can the artist do?

In the 1960s, just as Rachel Carson was publishing her landmark book Silent Spring—often referred to as the catalyst of the environmental movement—a new kind of visual art sprung to life. Through art created in outdoor environments rather than the white walls of a studio, “ecological artists” sought to illuminate the most serious environmental issues of their time. They revealed often-ignored details of the world with unorthodox mediums like graffiti, planted fields, and even mountains. Here are some lessons that their ecological artworks have bared about our planet in flux.

Earth is entering the Anthropocene

In a series of symbolic plunges, European ecological artist Jason deCaires Taylor has dropped numerous human-shaped monuments into the oceans and erected them on the seafloor. Taylor started this ongoing project in 2006, off the west coast of Grenada in the West Indies, where he created the world’s first undersea sculpture park.

Each of his nine projects represents a slightly distinct ecological intent—from calling out human ignorance of environmental issues, to creating synthetic habitat and aiding the growth of coral reef. With all his work, a pervasive theme stands clear: Humans are leaving an overwhelming imprint on Earth’s land and water. Many scientists agree that the humans’ far-reaching impacts have forced Earth into a new geological epoch: The Anthropocene. (Taylor tries not to contribute to the dawn of the Anthropocene: His work is made out of ocean-friendly, pH-neutral concrete.)

The underwater sculptor is currently working from the Canary Islands on an underwater museum for the Atlantic Ocean.

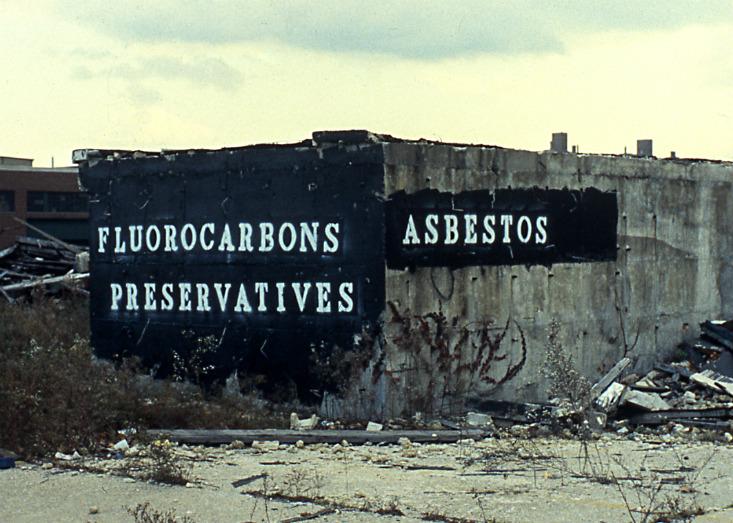

Toxic waste persists in your neighborhood

Once described in The New York Times as “an artist who works not only in New York, but with New York,” John Fekner uses his work to alert people to harmful materials in their community. One of his projects, Warning Signs, identifies the toxic substances found in New York City with phrases like, “Asbestos,” “Attack of the Toxic Tanks,” and “No Transportation of Nuclear Waste.” Fekner brings attention to local waste because as a painter, he writes, “you act as the eye of the community, for the community.”

We can play a helpful part in nature

Since 2007, Basia Irland—a sculptor, poet, installation artist, and professor emerita at the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque—reminds people that it is possible to play a beneficial role in the local ecosystem. Acting as a seed-disperser herself, the artist carves the shape of books from blocks of frozen river water, and within them places native seeds. She returns each “ice book” to its source stream, where it melts and releases the contained seeds. Each of Irland’s “book launches,” ranging from Ohio to Iran to Spain, involve the guidance of stream ecologists and botanists to ensure that the species chosen are good fits for each river system.

In her description of Ice Receding/Books Reseeding, Irland writes that as her seeds turn to plants along the riverbank, they sequester carbon, mitigate floods and drought, and filter out pollutants, thereby helping “riverside organisms, including humans.”

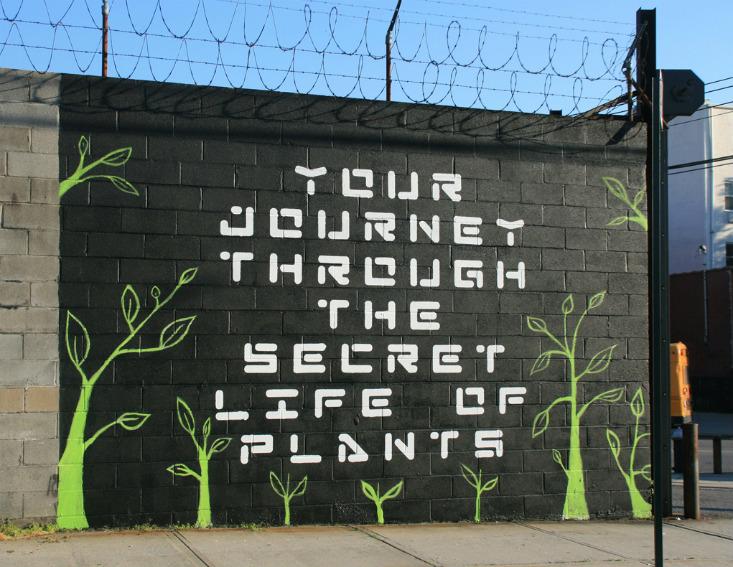

Nature is not meek; it endures in unexpected nooks

On a wall facing the Two Coves Community Garden and the Astoria Housing Development in Queens, New York, ecological street artists Fekner and Don Leicht painted a revamped version of the cover of Stevie Wonder’s 1979 album, Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants. In urban areas like this, growth comes between cracks in the sidewalk and blooms in ditches near train tracks and highways. The artists illuminate the environment’s scrappy ability to adapt and sustain. This project, reads Fekner’s description, “is an affirmation of hope and strength that Mother Nature will prevail whether it is a single plant species on a city street or an entire ecosystem threatened by man’s destructive ways.”

For more about nature blooming in NYC’s hidden spaces, see Brandon Keim’s article, “The Wild, Secret Life of New York City.”

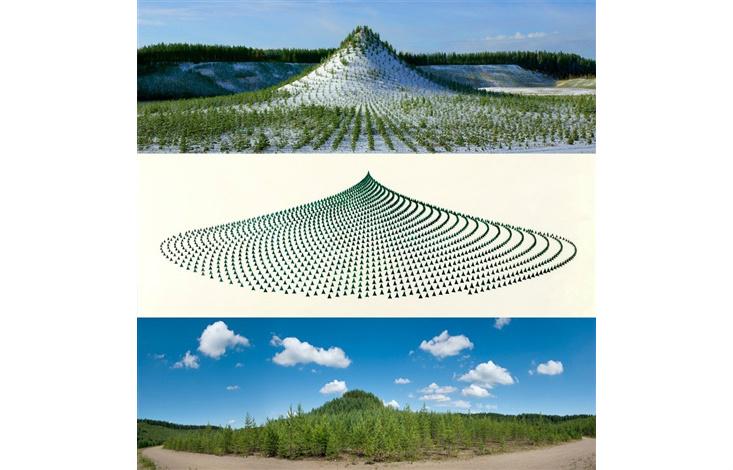

The natural world is not for this generation only to enjoy

In 1996 Agnes Denes, a pioneer of the ecological-art movement, sent a bold message in a suitably bold form. She arranged 11,000 people to plant 11,000 silver fir trees on a hill made over a reclaimed gravel pit near Ylöjärvi, Finland. Sponsored by the United Nations Environment Program and the Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Tree Mountain is now a protected space to be maintained for generations. Denes’ artist’s statement reads:

The forest will be kept for the next 400 years, thereby creating the first manmade virgin forest. It will take that long for the environment to re-create itself and a natural ecosystem to form. The 11,000 people who came to plant the trees received a certificate valid for four centuries that they can leave to their children as custodians of the trees.

To Denes, Tree Mountain symbolizes the human commitment to the future of our planet. In an essay she writes that her forest “re-establishes disturbed and destroyed land, creating roots to hold eroding land and keeping global warming down, photosynthesis up, cleaning ground water”—for the future.

Denes says she is now planning a forest of over 50,000 trees in an undisclosed New York locale she calls, “the last open space in a city of congestion.” She is also constructing a live, flowering pyramid in Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, New York.

Becca Cudmore is an editorial intern at Nautilus.