California is the the nation’s agricultural powerhouse, supplying nearly half of the fruits, nuts, and vegetables eaten in the U.S., and a quarter of its milk and cream. But the state’s terrible drought, now plodding through its third year, is costing the industry $1.5 billion annually in revenue losses and groundwater pumping costs, according to a recent report from the University of California, Davis. The impacts of the drought would be even more severe if the state were not pumping so much water from underground. If the drought continues for two more years, groundwater will grow increasingly harder and more expensive to pump, creating a “slow-moving train wreck” for key crops, according to Richard Howitt, lead author of the report.

Fortunately, California finally passed a groundwater management law last month in September, making it the last Western state to regulate this critical resource. By finally spurring policymakers into action, the drought might end up helping the state over the long term. “We should never let a good crisis go to waste,” says one of the new law’s authors, Assemblymember Roger Dickinson.

But has California really learned all it can from the current and previous water crises? There’s still a lot of opportunity to adopt clever ideas from jurisdictions both within the state and beyond that have already gotten serious about better water management in the face of growing population and a changing climate.

COUNTING WHAT COUNTS

You can’t manage what you don’t measure, and the Public Policy Institute of California points out that the state “woefully lags on information and analyses of water use, flows, quality, and costs—essential tools to support modern water management goals.”

The major obstacle to measuring water use is political opposition. “There are certain people who benefit enormously from a lack of information and inefficiency—and those people have lawyers,” says Peter Gleick, an independent expert on water issues. The people who benefit from the current situation are primarily farmers with longstanding rights to the state’s water, and they resist changes that might decrease their shares.

A lot of California cities don’t even have water meters for residential users. But Irvine in Orange County was an early adopter of meters and used that data to institute an allocation-based rate structure—a full 24 years ago, during a protracted drought. Customers each receive a certain amount of water to use at a low price. If they use more water, they are hit with rates up to eight times higher; thrifty customers receive a discount. Since its introduction of meters and graduated rates, Irvine residents have reduced their water usage by 50 percent per capita and are down to about 85 gallons a day per person, among the lowest in the state. Since Irvine led the way, many other cities in state and beyond have instituted similar policies.

LIVING WITHIN OUR MEANS

A key management principle is that you can’t allocate more water than you have. You might think this would be obvious, but in California, the state has allocated five times more surface water than it actually has, according to the recent UC Davis report.

Unfortunately, such over-allocations are surprisingly common around the world, from the multistate 1922 Colorado River Compact, to Australia before a spate of droughts prompted a series of water reforms over the last few decades. Over-allocations tend to happen because past decision-makers didn’t anticipate big increases in water demand that places like California have experienced. The way to fix this problem now is to convert rights for set quantities of water into shares of total water available, says Mike Young, a water-policy researcher at the University of Adelaide who played a key role in crafting his country’s water management reforms. Instead of giving a resident a fixed amount of water each day, they would get one share of the jurisdiction’s water resources. If the area’s population booms, many more shares are distributed and the shares consequently get smaller, so both new arrivals and long-time residents are forced to conserve. “You cannot give anybody a guaranteed volume,” says Young.

WISDOM OF CROWDS

One way California and other jurisdictions have tried to introduce flexibility into the existing system is by encouraging rights holders to sell water. However, when farmers choose to sell their water in California, they are legally obligated to fallow some of their land. This rule is based on the assumption that farmers need and use all their allocated water, so if they sell some, they must not be using all of their land. However, many farmers may not need to use all the water they’re entitled to; the rule ignores the possibility that they could use water more efficiently, and sell the water they’ve saved. This law has been a disincentive for farmers to, say, upgrade to water-efficient drip irrigation.

What’s more, a “use it or lose it” clause in state law serves as an incentive for profligate use. “At the moment, a person who is efficient runs the risk that they might lose their water right,” says Young. “Changing it around as Australia did 20 years ago—if you save the water, it’s yours and yours only to sell—inspired lots of innovation.” Of course, that requires compulsory water metering.

As a result of the changes in Australia’s laws, the value of senior water rights increased 20 percent a year for the first decade after that reform was implemented, said Young. “Markets understand where there’s an opportunity,” he said. And today Australia’s farmers and city-dwellers are using less water than ever before, leaving more for the environment and more as a buffer in times of drought. The government helped eased this transition by putting up billions of dollars for farmers to invest in more efficient irrigation technology. And after scientists concluded that the initial carving up of water shares left too little to natural ecosystems, the government paid billions more to individuals to buy rights to water that would stay in the environment.

UNDERGROUND BANKING

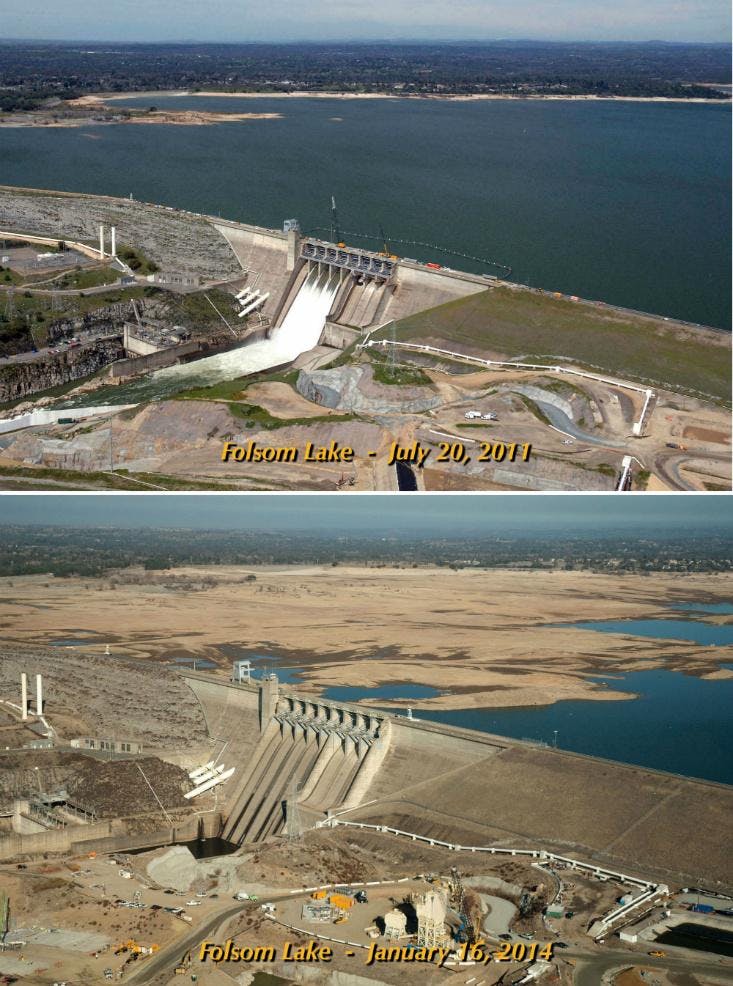

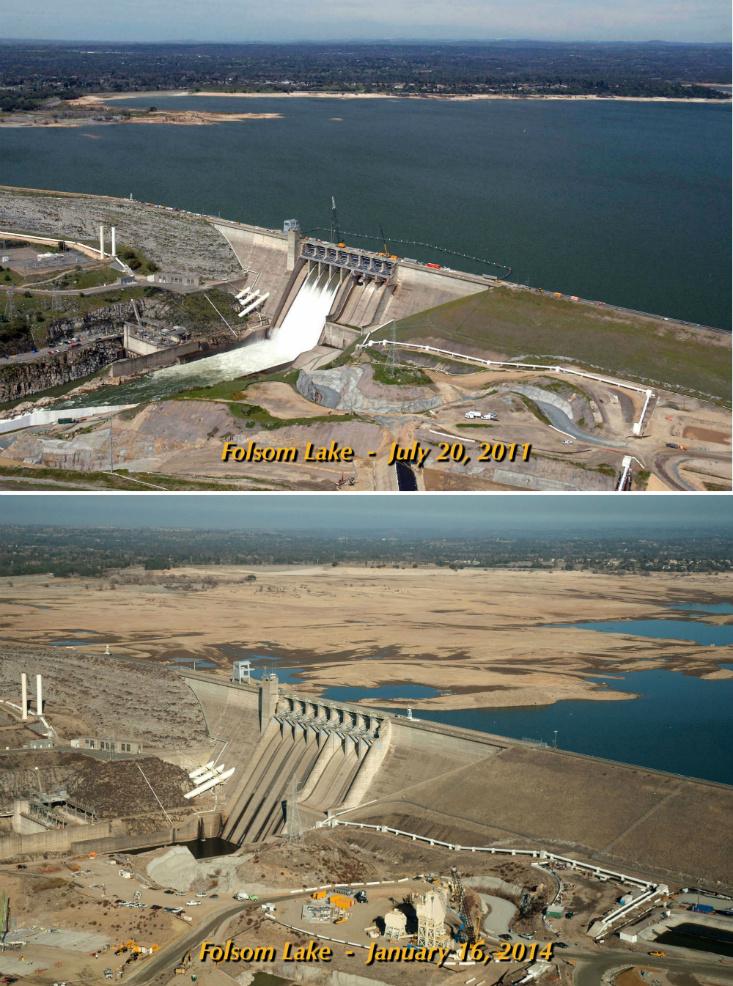

Groundwater banking allows managers to store water in underground aquifers for dry years. Unlike surface storage, groundwater storage doesn’t risk flooding nearby neighborhoods, and it doesn’t evaporate. And California desperately needs new storage because climate change is reducing the Sierra Nevada snowpack (pdf, pages 6–7), which has traditionally released winter water slowly throughout the spring and summer.

While legal uncertainties about water ownership are limiting this approach statewide, one water district near Sacramento is moving ahead anyway. Fair Oaks Water District is located along the American River and has plentiful water rights. Although the drought hasn’t cut its water supply, it’s proactively developing groundwater as a backup supply, says Tom Gray, the general manager. “In wet years, you use surface water because there’s plenty, and you reserve the groundwater. Then when dry years come and surface water is limited, we’d go to groundwater.”

But banking water must be balanced with current needs, too. Fair Oaks pumped water from its underground stash this year, even though it didn’t need to, so as to leave more water in the river for other users and for the environment. Gray said the river is a cornerstone of area tourism and the economy, and that water for customers must be balanced with river health. This approach is part of an active management plan among local water districts, environmental groups, and businesses. It is proscribed in a signed agreement called the Water Forum.

“Instead of fighting and going to court, we’ve come together and said we’ll act in this way,” says Gray. “Most people are living it.”

Erica Gies is an independent journalist who writes primarily about the core requirements for life: water and energy. Her work appears in various outlets, including The New York Times, The Guardian, Ensia, Scientific American, and The Economist. She is a co-founder of ClimateConfidential, a news startup that illuminates the crossroads of environment and technology.