It was the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, 1897. Through a periscope, England was sailing along in all its hope and glory. That summer Edward Elgar turned 40 and was slowly emerging as the country’s greatest composer. For the jubilee he’d written The Imperial March, a foreshadowing of the Pomp and Circumstance marches that would make him famous. Earlier in the year he’d presented King Olaf, a foreshadowing of the choral and orchestral works that would make him great, including The Dream of Gerontius and Variations on an Original Theme (“Enigma”), known as the Enigma Variations.

In the middle of that July, Elgar was in the midst of writing a new festival work, Te Deum and Benedictus, working inside a large tent set up in the front garden of the house in Malvern, in the south of England where he lived with his wife and daughter. Above the tent, a flag fluttered to signify the composer was at work. Inside, amid scattered music sheets, Elgar wrote furiously, occasionally stopping to muse on a 40-mile view of the hills and heaths, and the Druid ruins that inspired him.

Elgar was ever the mercurial outsider—a tall, thin man with his bully moustache, the countenance of an ascetic atop a footballer’s body—the son of a piano-tuner, completely self-taught, “from harmony to fugue,” an early biographer wrote, hurried and self-divided, always in and out of love with music, always tossed between exuberance and despair, and forever obsessed with ciphers, riddles, and word tricks, not to mention his passion for “public mysteryfication,” as music critic and his longtime friend Ernest Newman put it.

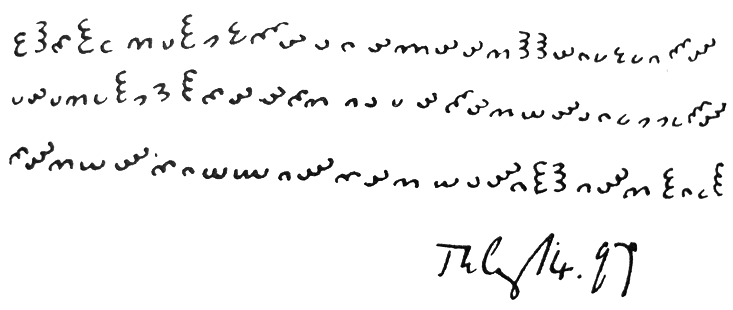

On July 14, following a visit the previous weekend to some family friends, the Reverend and Mrs. Alfred Penny, Elgar spun off what looked like a drawing or scribble and gave it to his wife, Alice, to attach to a thank-you note. It was intended for Dora Penny, a 23-year-old ardent admirer, who sang in a local choral group and liked to dance.

They’d known each for a year and a half; she was not a lover, rather an entertainment, a colorful Aquarian butterfly with which to go biking, kiting, and strolling through the bracken and harebells of Malvern; someone who could read music well enough to turn the pages at the piano bench, but with whom he could also could talk about maps, fashion, and the fortunes of the Wolverhampton Wanderers football team. He nicknamed her Dorabella.

Elgar’s scribble was actually a cipher. It consisted of 87 glyphs unevenly spread over three lines. It contained 24 different symbols that featured one, two, or three cusps or curves. The glyphs were tilted in what appeared to be eight various angles. In a glance it gave the sense of seagulls, or sheep, or bits of stubble. Dora looked at it, couldn’t figure it out, put it in a drawer, and didn’t draw it out again for 40 years.

The scribble, known as the Dorabella Cipher, has never been decrypted and stands with such other famous unsolved puzzles as the Voynich Manuscript, a 240-page codex dating from the 15th century; the Phaistos Disk, an apparently Bronze-age piece of clay found in Crete in 1908; and the Zodiac Killer ciphers of the 1960s and ’70s.

Countless cryptographers have ardently attempted to crack the Dorabella Cipher, employing deft math and analysis. A few quite accomplished cryptanalysts insist they have solved it. But the Elgar Society begs to differ. They’re the self-acknowledged arbiters in the matter, the Union Jack flying proudly above their whistling teapot. Their argument is that any solution must decode the cipher and, at the same time, be self-evident, so that Elgar aficionados everywhere can turn to each other and agree, “Of course. Why didn’t we see it?”

That the solution to the Dorabella Cipher appears so subjective contradicts the traditional notion that solving ciphers is a purely mathematical affair, leading to a single answer determined by excluding all others. But such is the nature of great riddles.

Marcel Danesi, a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto and author of The Puzzle Instinct: The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life, offers that puzzles like the Dorabella Cipher are the Sphinx at the gates of Thebes. Trying to solve them “is similar to finding the great answers in philosophy or science,” Danesi says. “It’s a process that leads to innovation and a deeper understanding of the world. There’s a metaphysical aspect to it. Puzzles promise to order our lives, if only we can detect a deeper pattern.”

Artists by nature are puzzle makers. In their work they ask us to piece together elements to reveal patterns and meanings, stirring our imaginations, promising catharsis. Elgar, a consummate artist, loved to puzzle and intrigue his friends and audiences. Whatever its solution may be, if it ever comes, the one thing for sure about the Dorabella Cipher is that it is written in the key of Elgar.

In the 1890s, cryptography puzzles were popular. Lewis Carroll was a puzzle master of the day, as was John Holt Schooling, a statistician and amateur conjurer of the day. His ciphers often appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette, “written by gentlemen for gentlemen.”

In 1896, Schooling created a “Nihilist” cryptogam, a brief encrypted message, which he claimed no one would solve. In Nihilist cryptography, the encryption and decryption keys are the same; Russian Nihilists used the system against the tsar in the 1880s. Elgar stayed up one night and solved the puzzle, making notes on some sheet music for Cockaigne, his musical portrait of London.

Elgar was always fiddling with such things. His daughter’s name, Carice, combined letters of his wife’s first and middle names, Caroline and Alice. He gave violin and piano lessons to daughters of a local headmaster and used the letters in their last name, G-E-D-G-E, to create a musical cryptogram—a series of notes—and the motif for an allegretto. Incidentally, this particular bit of music is reminiscent of Robert Schumann, who was also drawn to ciphers and created elaborate cryptograms in pieces.

Artists by nature are puzzle makers. In their work they ask us to piece together elements to reveal patterns and meanings, stirring our imaginations, promising catharsis.

Elgar’s obsession with creating and sustaining mysteries would find its most famous form in his Enigma Variations, which debuted in 1899. The 32-minute masterpiece, scored for orchestra with organ, was a series of musical sketches, employing cryptograms, of his friends, including his friend’s bulldog and Dora. “Well, how do you like that—hey?” he said to Dora when he’d finished playing the variation about her. She felt a “whirl of pleasure, pride, and almost shame that he should have written anything so lovely about me,” she wrote in her 1937 book, Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation. She added that she had no idea what the music “meant,” although it later occurred to her she had been a victim of Elgar’s “impish humor,” because in the music he caught her tendency to stammer when nervous.

The Dorabella Cipher entered the annals of cryptography almost as an afterthought, when Dora published a copy of it in an appendix to Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation, remarking, “I have never had the slightest idea what message it conveys.”

In fact, it is a classic, coded message. It is—or appears to be—based on a substitution system, in which each glyph represents one or more letters, using a known, if obscure alphabet. From the start, cryptographers faced two fundamental obstacles to breaking it. One is that the cypher defies frequency analysis. In any language, certain letters are used more often than others, and that particular distribution enables cipher analysis. But with Dorabella there aren’t enough characters to analyze.

Then there’s the historical mystery, reconciling the sophistication of the riddle with the relationship between sender with receiver. Elgar had known Dora for 20 months and had sent her two other notes in that time. There’s no indication he sent her any other ciphers, either before or after July 1897. Moreover, Elgar made no attempt to conceal the cipher, giving it to his wife to deliver. Why would he send such a riddle to someone he knew only casually and who seemed to have little interest in solving puzzles? What was there to hide from Dora?

The first “solution” of consequence was offered in 1970 by Eric Sams, a wunderkind who went to Cambridge at 16, worked in British intelligence during World War II and went on to become both a notable Shakespeare scholar and a musicologist. Interestingly, he wrote a good deal about the way such composers as Schumann and Brahms embedded codes in their music. He died in 2004.

Sams proposed a solution to the Dorabella Cipher based on the alphabet, Greek characters, and phonetic spellings. (He claimed Elgar had gotten his glyphs from a cypher manual written in 1809.) Sams devised a key to link Elgar’s symbols—based on their frequency in the series, their shape and angle—to vowels and consonants. With his key in hand, he proposed that the cipher read:

STARTS: LARKS! IT’S CHAOTIC, BUT A CLOAK OBSCURES MY NEW LETTERS,

A, B (alpha, beta, i.e., Greek letters or alphabet)

BELOW: I OWN THE DARK MAKES E.E.

SIGH WHEN ARE YOU ARE TOO LONG GONE.

In a footnote, Sams wrote that the “train of thought” represented in his solution—“chaos, cloak, obscures, letters, alphabet, dark, sigh, absence”—along with a reference to Dora’s name for him, “E.E.,” made his rendering “authentically Elgarian.”

Sams’ decryption remained well regarded, if not regarded as correct, among Dorabella Cipher sleuths for decades. The best of the Dorabella Cipher devotees were drawn together in 2007, when the Elgar Society sponsored a competition to decode the famous note. It promised 1,500 British pounds to the winner. Kevin Jones, Emeritus Professor of Music at Kingston University in London, who chaired the judging panel, explained the solution had to be methodically sound and also “glaringly obvious.”

There were seven serious attempts, which followed either one of two tacks. One was a conventional decryption strategy, using substitution, and a list of arbitrary characters, which could then be translated into a plaintext message roughly matching an Elgar reference. The other approach was to construct a reasonable decryption and then “work backward” to legitimize the process, using, as Jones puts it, “any number of special cases, of conjectured errors on Elgar’s part, or impossible complex procedures: combinations of shuffling, displacement, or changing keywords.”

One solution that Jones found compelling was by Tim S. Roberts, an adjunct senior lecturer at Central Queensland University in Australia, and an inveterate puzzle solver. “I have an attested IQ of over 170,” he told Nautilus in an email. “But, unfortunately, I am fairly useless at almost everything except puzzles.”

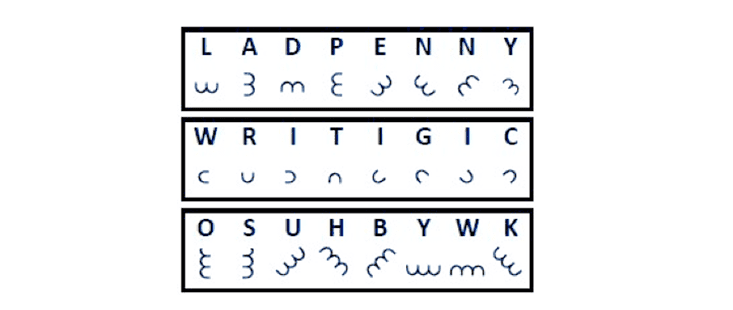

Roberts approached Dorabella pragmatically. He assumed that the message was of little significance; that it was in English; and, considering Elgar’s tendency to write music quickly, might well have errors. He also assumed that given Dora’s lack of knowledge about ciphers the message was relatively straightforward. From that he adopted a substitution approach, but with one difference from a traditional strategy, in which there’s a one-to-one correspondence between glyphs and letters in the alphabet. Roberts decided that two glyphs could represent the same letter, which he points out was the same technique used to decipher Mayan symbols.

Eventually, he found a key, which he deciphered by finding the name “Penny” within one set of the symbols in the cipher. His key was, “Lady Penny, writing in code is such busy work.”1

He applied that to his alphabet table and came up with this plaintext:

P.S. Now droop beige weeds set in it—pure idiocy—one entire bed! Luigi Ccibunud lovingly tuned Liuto studio two.

As part of his entry, Roberts wrote that the solution “is simply two thoughts put together… The first refers to gardening, which is mentioned briefly in Dora’s diary entry from a few days before; the second refers to a musical composition by one of Elgar’s greatest influences at this time (Luigi Cherubini). Perhaps Elgar’s three greatest interests at this time were, in order, music, puzzles, and gardening—it is wonderfully exciting that this particular little note is highly relevant to all three!”

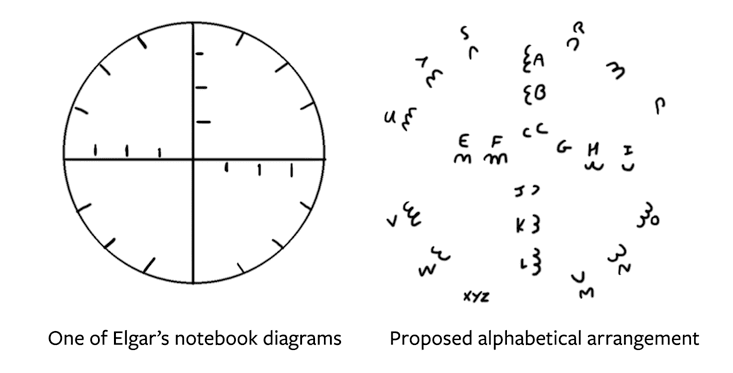

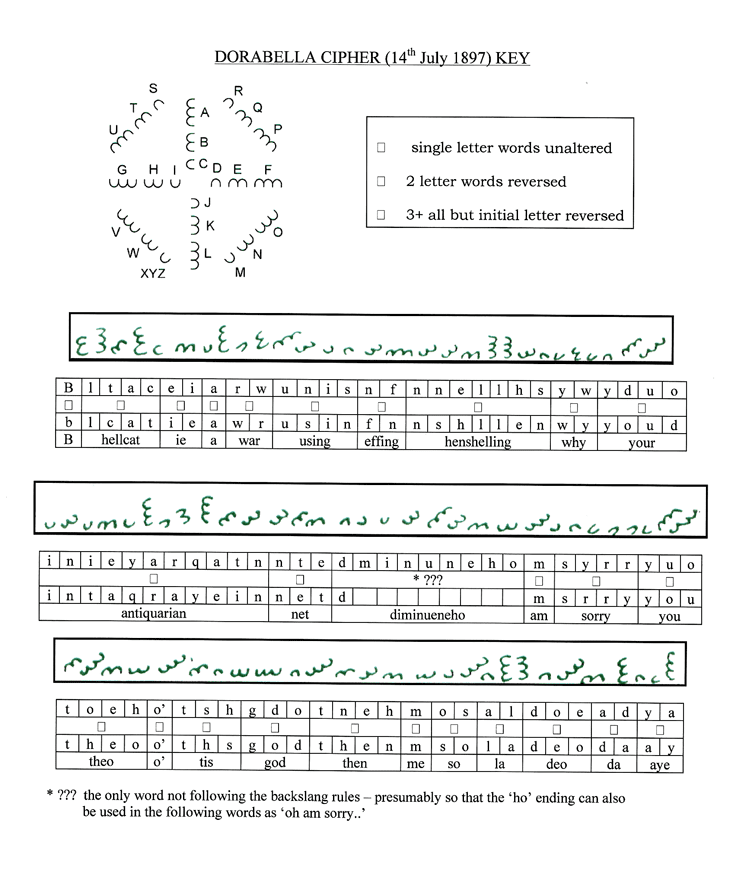

Another notable contestant was Tony Gaffney, an amateur cryptographer, who has solved several challenging ciphers. He asserted Elgar fashioned an alphabetic key for his symbols based on a clock-like diagram in one of his notebooks.2 With that key, Gaffney maintained, the symbols spelled:

BLTACEIARWUNISNFNNELLHSYWYDUO

INIEYARQATNNTEDMINUNEHOMSYRRYUO

TOEHO’TSHGDOTNEHMOSALDOEADYA

Gaffney noted that Elgar loved and often used phonetic spellings (“My Dear Dorabellllla—How many ells long is that”) and “backslang,” where, for instance, the word “cipher” becomes “crehpi.” Applying backslang to his alphabetic rendering of the note, inserting word divisions, and taking into account phonetic spellings, Gaffney determined the note read:

B (Bella) hellcat i.e. war using ?? hens shells is why your

antiquarian net diminishes hem sorry you

theo oh ‘tis God then me so la do E (Elgar) Adieu

In a footnote to his solution, Gaffney wrote, “The first line didn’t make much sense to me until I remembered seeing the following in a letter from Elgar to Dora Penny dated Sept. 24, 1898: “… and then some Sunday at Wolverhampton you can give us tea and fire eggs at me as of yore.”3

After the entries were analyzed, Professor Jones and his panel did not find a winning solution. In a statement following the competition, Jones praised some of the entrants for “impressively ambitious and thoughtful analysis.” But he was little impressed that some sleuths relied on phonetic interpretations of letters and words. Those solutions, he wrote, “read as a “disconnected chain of bizarre utterances, such as an imaginative mind could conjure up from any group of random letters, and make little sense.” (Gaffney didn’t take defeat lightly. “Who are the Elgar Society to tell me my solution is wrong?” he wrote to Nautilus in an email.)

Nick Pelling, a British programmer, hosts a popular website for cipher hounds, Cipher Mysteries, and wrote a self-published book, The Curse of the Voynich Manuscript: The Secret History of the World’s Most Mysterious Manuscript. His take on why the kind of solutions proposed by Roberts and Gaffney don’t work is because they offer “a convoluted attempt to decrypt the cipher itself, but no solution at all to the historical mystery. And you need to solve both at the same time.”

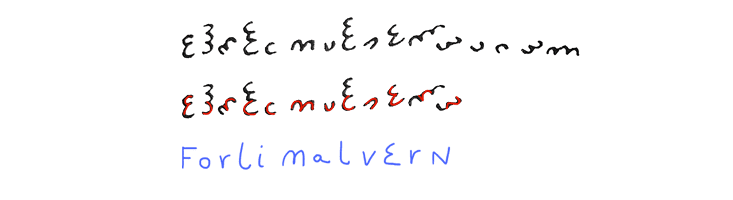

Pelling has come to believe the Dorabella cipher is actually a “non-mathematical stegotext”—in effect, a graphic cipher, a picture. He took Elgar’s habit of starting correspondences with his address, which that summer of 1897 was his house in Malvern, which the Elgars named “Forli” after an early Renaissance Italian artist who painted angels. Using those words as a crib, Pelling came up with a beginning of plaintext:

Pelling hasn’t gone further but his conviction, he wrote on Cipher Mysteries, is that “what we are looking at could well be more like Elgar’s improvised steganographic attempt at a mind-reading trick than a traditional ciphertext.” That is, perhaps what is “glaringly obvious” about Elgar’s note is it is simply a pictorial reference to where he and Dora crossed paths a few days earlier. Maybe she just didn’t see it for what it was.

That Dora Penny never expressed much interest in the cipher seems strange, not least because two years later she had the opposite reaction to the musical mysteries related to the Enigma Variations—the theme that inspired the piece and the underlying theme throughout. She noted in her memoir, “I almost lay awake at night thinking and puzzling, and all to no purpose whatever.”

Indeed, at one point she became so annoyed by it all that she confronted Elgar and demanded to know the secret. Was the theme “Auld Ang Syne?” Was it a Mozart reference? He looked at her in a “sort of half-impatient, half-exasperated way and snapped his fingers, as though waiting for me to think of the tune there and then,” she wrote. “I always feel looking back to that moment, that he was on the point of telling me what it was, and then he just said: ‘I shan’t tell you. You must find it out for yourself.’ ”

Years later Dora would claim that the tune was “Auld Ang Syne,” and Elgar had lied because the truth was he didn’t want her to guess it, or anyone else for that matter, whether because “Auld Ang Syne” seemed an unbecoming solution, compared with say a Mozart reference, or because he wanted to keep all the mysteries surrounding the Enigma Variation secured.

Julian Lloyd Webber, an acclaimed cellist, and younger brother of composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, is the president of the Elgar Society. He has come to see the cipher, and all the other aspects of Elgar’s affinity for mystification, as the heart of the brilliant composer. “I think he set out to intrigue and puzzle people, knowing that they would talk about him—at the time the works were written and also long afterward,” Lloyd Webber says. “There was also a mischievous side to him. He liked playing tricks on people, and one of those tricks might have been to send that poor girl that thing that was completely undecipherable and he knew it.”

Mark MacNamara is a senior writer for San Francisco Classical Voice. He has written for Salon, Stanford Social Innovation Review, and Vanity Fair.

Footnotes

1. This September, Roberts revised his key to read, “Lady Penny, writing in a code is a way to keep busy.” His new key, he explains, removes an anomaly from the ordering of the glyphs in Elgar’s third line. His revised plaintext reads:

P.S. Now droop beige weeds set in it—pure idiocy—one entire bed! Luigi Ccibunud luv’ngly tuned Liuto studo two.

2.

3. After the story was published, cryptographer Tony Gaffney informed us that he had amended his text solution to read:

B (Bella) hellcat ie a war using effing henshelling why your

antiquarian net diminueneho am sorry you

theo o’tis god then me so la deo da aye

Here’s the “backslang” key to his solution:

This article originally appeared in our “Secret Codes” issue in October 2013.